Nearly 50 years on, we look back at the “curse” of The Omen

Ahead of The First Omen, in cinemas next month, Matt Glasby looks back at the 1976 original’s most questionable legacy – the persistent idea that it was cursed.

On the sixth day of the sixth month of the year 1976—an auspicious date if ever there was one—The Omen was released upon a not-exactly-unsuspecting public. It made millions at the box office, started a franchise that continues to this day, and eventually won over the critics, with The Washington Post calling it “the classiest Exorcist copy yet”.

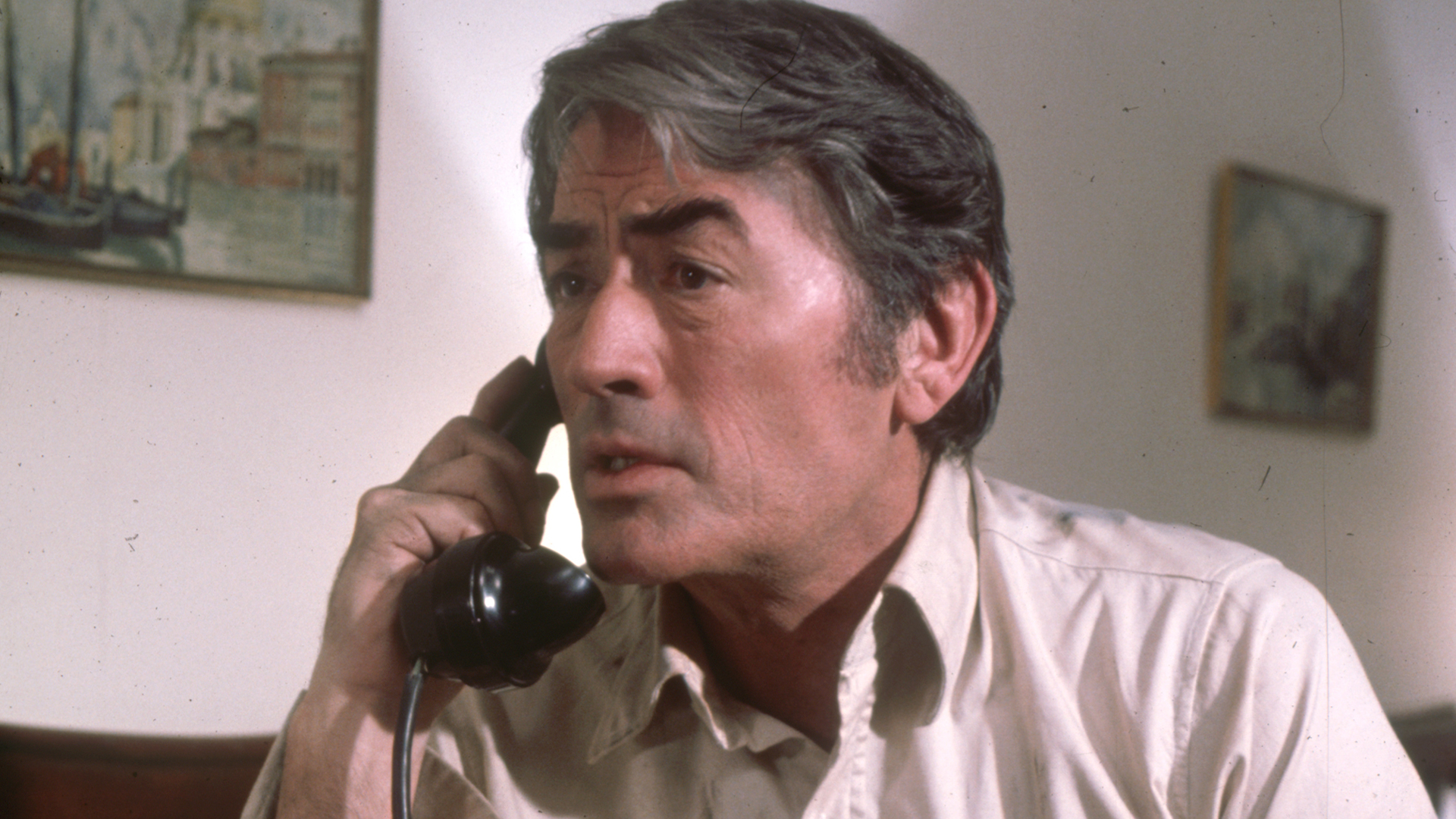

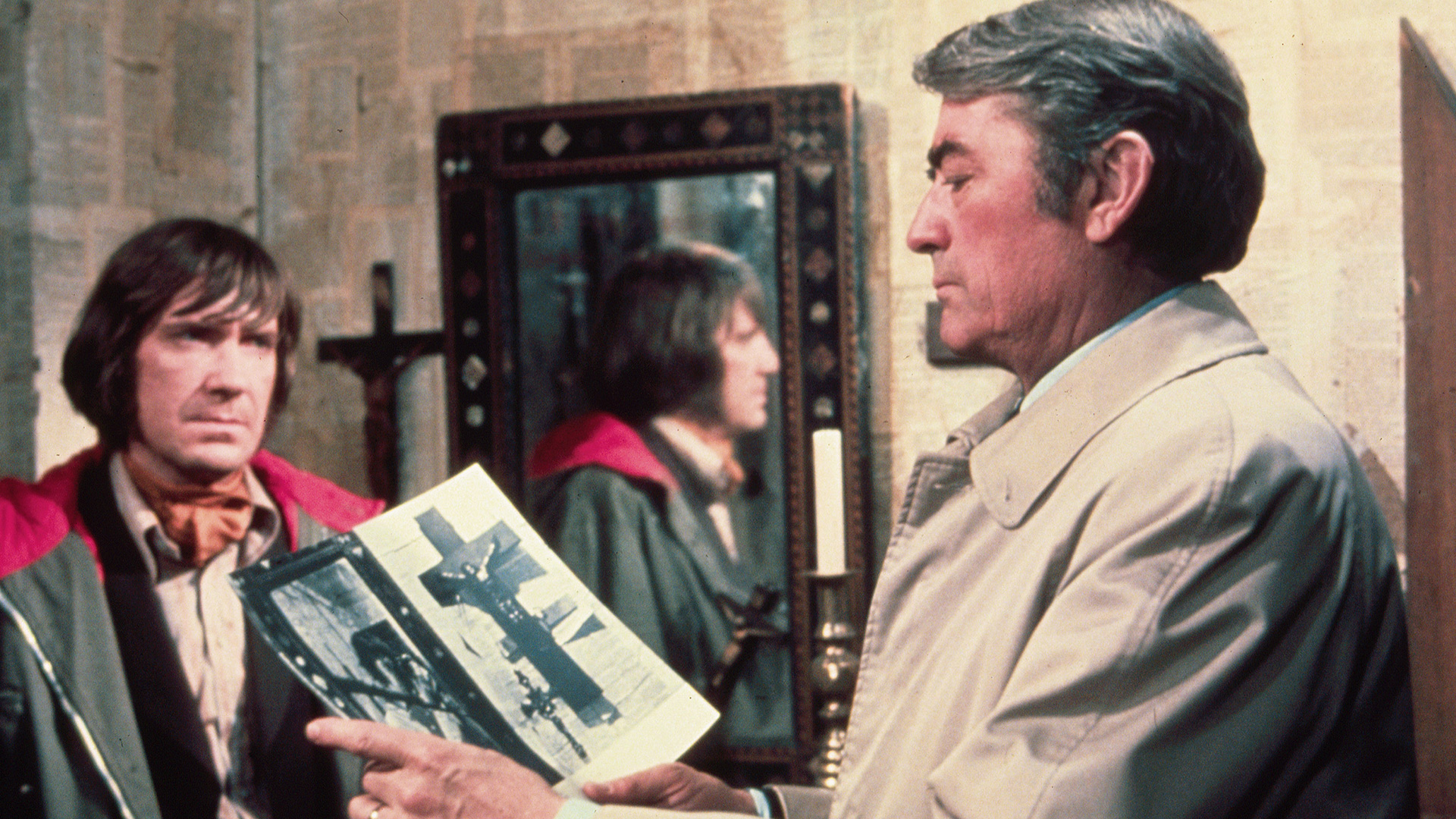

Perhaps it’s the interplay between classiness and crassness that gives the film its power. In the classy corner are the cast, headed by Hollywood legend Gregory Peck; director Richard Donner, a seasoned pro who would go on to make Superman, Lethal Weapon and The Goonies; and composer Jerry Goldsmith, who would win an Oscar for his troubles. In the crass corner are the showstopping death sequences that would help inspire the Final Destination franchise, among others.

The plot concerns diplomat Robert Thorn (Peck) and his wife Kathy (Lee Remick) whose (secretly adopted) child Damien (Harvey Stephens) turns out to be the Antichrist. To protect him, the forces of evil strike down everyone in his path, from meddling priest Father Brennan (Patrick Troughton, AKA The Second Doctor), who gets turned into a human kebab, to photographer Keith Jennings (David Warner), who’s decapitated by a plate of glass.

The film spawned three sequels and several TV shows, but one of its greatest legacies—and also firmly in the crass corner—is the persistent idea that it was cursed.

The facts are these. In June 1975, two months before shooting started, Gregory Peck’s 30-year-old son Jonathan shot himself dead. Peck senior went ahead with filming, but—understandably—struggled with scenes of violence involving Damien.

Then, while flying to the London set, his plane was hit by lightning. Then, producer Mace Neufeld’s plane was too. Then writer David Seltzer’s.

Worst of all, a plane they had intended to film with—but had decided, last minute, to hire another day—crashed when a flock of birds flew into its engine, killing everyone on board, and the wife and children of the pilot, who were driving past at the time. It’s no wonder producer Harvey Bernhard carried a cross, concluding, “The devil was at work and he didn’t want that film made.”

There was more to come. On set, a stuntman was badly bitten by a rottweiler. Baboons in the safari park scene went crazy, terrifying Remick and Stephens. The next day a keeper was killed by a tiger.

Back in London, Neufeld’s hotel was bombed by the IRA, and so was a restaurant Peck had booked for them all.

But, as is often the case, it was the below-the-line talent who suffered most. On his next film, A Bridge Too Far, stuntman Alf Joist fell off a building, missing the airbags below. When he woke up in hospital, he said he felt like he had been pushed.

The creepiest incident came when special effects designer John Richardson was driving through the Netherlands with his assistant Liz Moore. A car hit them head-on, cutting Moore in half, much like the Jennings death scene that Richardson designed. When he stumbled from the wreckage, a signpost told him he was 66.6km from the town of Ommen. The date? Friday the 13th 1976.

Over time, these terrible events have been parlayed into a curse, no matter how offensive this is to the memories of those who died. But bad health and safety has always made for good PR.

As far back as 1968’s Rosemary’s Baby, canny studios have been calling films about Satan cursed to scare up the column inches. They were still doing it by the time Darren Lynn Bousman shot 2011’s 666: The Prophesy (aka 11-11-11) in Barcelona. On set—a derelict house by the coast with all sorts of rumours swirling around it—the director told journalists of finding a spooky secret room and Arabic scrolls buried around the grounds, mysterious accidents befalling the crew, and a ghostly presence in the basement. They were clearly spooked, but they also had a low-budget film to promote.

Then there’s the maths. Films are made by hundreds, sometimes thousands, of people over the course of several years. Bad things will inevitably happen to some of them.

The so-called Poltergeist curse involved the deaths of four cast members over six years, most notably series star Heather Rourke (who died aged 12 of congenital bowel disease) and Dominique Dunne (who played Rourke’s older sister, and was killed by an ex-boyfriend aged 22). While these incidents are undoubtedly tragic, they’re not proof of a curse. Rourke’s untimely death, alongside those of cast mates Julian Beck and Will Sampson, all related to pre-existing medical conditions, so it’s ridiculous to blame them on something supernatural.

Indeed, if you’re looking for a film with the highest cast mortality rate, try 1985 sci-fi Cocoon. In the 20 years after it was released, seven of the main 18 cast members passed away. But then, it was set in a retirement home.

The Omen curse will, no doubt, go forth and multiply, especially if the prequel is successful. But as writer Josh Winning puts it in his excellent film industry horror novel Burn the Negative, “The idea of a movie curse is exciting. It’s thrilling. It makes us wonder and analyse and feel horrified all over again. At some point, though, we have to confront reality. The true horrors that lie outside of the cinema.”