No, ‘Me Before You’ Isn’t Telling Disabled People to Kill Themselves

***Me Before You spoilers ahead***

Spongy, smoochy, seemingly innocent romance flick Me Before You triggered a group of disability advocates to protest outside Wellington’s Embassy Theatre recently, urging people to boycott the film. As reported by Radio NZ, the crowd were not supportive of the film’s depiction of the disabled lead, chanting “assistance to live, not assistance to die” and “tell sad stories about your own lives”.

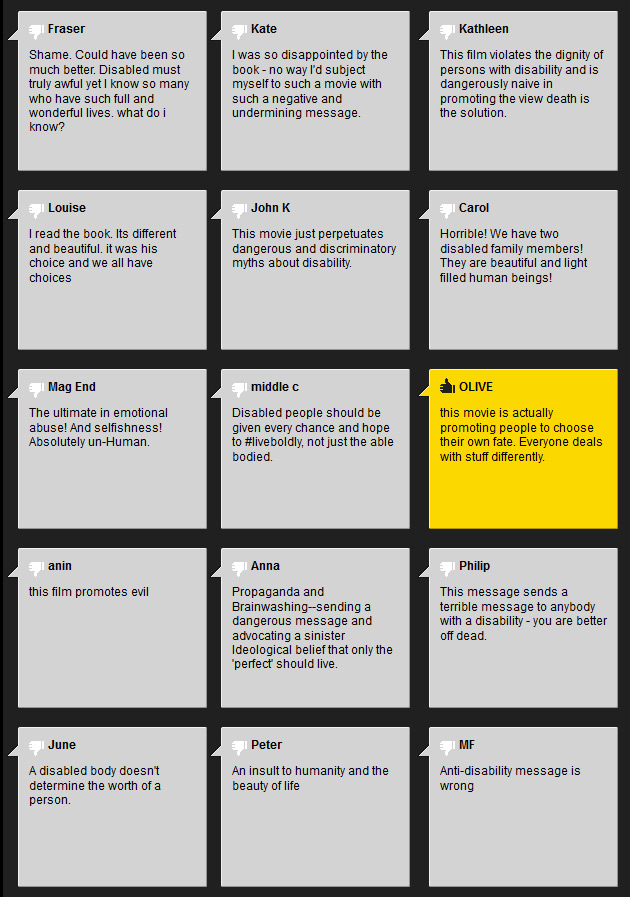

Flicks has also seen a stack of comments laying the smackdown on the film for similar reasons…

Part of the outcry is understandable. Having a disability doesn’t mean you’re useless or unable to live a fulfilling life, yet the vast majority of mainstream films that prominently feature a physically disabled character typically use that disability to make the audience feel sorry for them. If I were physically disabled and every character I saw on screen who was like me was treated with an “aww, it must suck so much being you,” that would be pretty bullshit.

The only physically disabled people I can think of who break this mainstream mold are Professor Xavier and Hiccup from How to Train Your Dragon 2. But as dope as psychic mutants and airborne vikings are, they’re not exactly based in the real world.

As with a lot of outrage, this frustration has culminated to a point where Me Before You is copping it large. One of the comments directly claims that the film “sends a terrible message to anybody with a disability – you are better off dead.”

This is where outrage boils over, and I don’t think the film “promotes evil” as some people claim.

Will, played by Sam Clafin, is handsome, rich, and white – everything that you could want in season three of The Bachelor. Bestowed with the best life ever (earned or otherwise), the movie shows how he’s built his identity on being out and active. That identity gets taken away when he becomes disabled after a motorbike accident.

Will becomes bitter. He’s not able to recognise himself anymore which, in turn, makes him blind to the bountiful possibilities he still has in life. This blindness fuels his first suicide attempt, and can therefore be claimed as him finding a horrible way out of being disabled.

But Me Before You does not favour this idea. In fact, the film’s against it, making use of its 109 minute running time to prove that Will’s thinking is wrong.

This is when Emilia Clarke’s character, Lou, steps in as Will’s caretaker, relentlessly assaulting him with aggressive positivity. They meet. They fall in love. It’s all synchronised to Ed Sheeran’s voice. It’s kinda sweet, like licking the frosting off a supermarket doughnut, and is aimed to prove that Will’s first suicide attempt would have been a terrible mistake.

And yet, he still decides to kills himself.

Lou cannot understand his decision at first, and the film shows her being angry and upset about it. But while his decision to end his life hasn’t changed, the reason why has.

The film mentions on numerous occasions how much excruciating pain he feels on a daily basis – pain he hides frequently from Lou. The condition is set to get far worse for him, with the film stamping home that he has no hope of getting better. He doesn’t want the remaining days/weeks/months/years of his life to be in sprawling agony. He wants it to be spent happy while his spinal cord still allows it. The film wants to emphasise this change in attitude.

This isn’t to say Me Before You is a great film (it’s not) or that it couldn’t have sold its message better (it could have) but to say it’s about “a man who is suicidal because he has been left paralysed after an accident” can be a tad misleading. There’s more going on in Will’s condition; it’s just that the movie doesn’t fully show this to you, and that’s somewhat problematic.

The film fluffs out a heavily sanitised brand of romance, so there are no scenes of Will wailing in excruciating pain (we are only told this). By refusing to show Will at his worst, the film wants the audience to be surprised – like Lou – by his decision in a way that provokes the message “you can never understand a decision like this until you’re in this person’s shoes.” But by sticking to this perspective, we aren’t exposed to the experiences that are supposedly worse than death, which is the main justification for Will’s decision to end his life.

Euthanasia is a very heavy and complex subject for such a light and simple film. By not going deep into it, Me Before You wisely avoids the minefield of saying “this is how suicide works…” and settles for “suicide is complex”. But at the same time, it leaves a large grey area that begs for further insight – one that the film does not provide. It makes an ethically-challenging theme even hazier, so we shouldn’t be surprised that some people take away the idea that the film “sends a terrible message to anybody with a disability – you are better off dead.” But they are also incorrect.

If there’s anything positive that can be taken away from this, it’s that it can spur a healthy conversation about euthanasia. In New Zealand, there are groups for and against end-of-life choice that might be worth your time.