A detailed look at the Cannes films at NZIFF by someone who’s seen ’em

Sarah Watt’s time covering this year’s Cannes Film Festival set her up perfectly for an in-depth preview of the films that have made it to this year’s NZ International Film Festival programme.

No fewer than 25 of this year’s New Zealand International Film Festival’s bountiful offerings come straight from screening at the Cannes Film Festival in May. As we are one of the first festivals in the world to be able to harvest the best of Cannes, Kiwi audiences should count themselves lucky.

But as all keen cinephiles know, working your way through the festival programme and planning your jaunts into cinematic darkness can be overwhelming. Here is a brief, spoiler-free rundown of what some of those Cannes films can promise.

The Jury Prize (this year awarded as a joint third prize) went to two exhilarating films. Les Misérables is not a musical (and in fact even purposely eschews the cliche of hip-hop songs in its soundtrack), but its preoccupation with a struggling society, corrupt cops, well-meaning criminals and cheeky urchin children all bring a contemporary take on Victor Hugo’s tale from 250 years ago. The characterisation and dialogue is naturalistic, tensions run as high as the stifling summer temperatures, and even though the narrative may feel familiar to those of us raised on crime dramas, this rendition feels fresh and meaningful.

Bacarau

Joint-third and equally deserved, Bacurau is categorically Must-See cinema, about which the less you know, the better. The initial premise of a young woman returning to her village for a funeral may feel like a well-trodden path—but following an enthralling set-up (thanks again to strong performances and a genuinely illuminating portrait of rural Brazilian life), the villagers begin slowly to realise that their home town is disappearing from maps. If that doesn’t sound mysterious enough, the film then leads us into completely unexpected territory which will have audiences gasping in shock and delight. Give it a go.

French director Celine Schiamma impressed me and past festival audiences with her contemporary tales of the feminine, Tomboy and then Girlhood. With her award-winning Portrait of a Lady on Fire she travels back in time to a remote island in Brittany in 1770 where a pipe-smoking, gutsy and independent artist is commissioned to paint the wedding portrait of a reluctant bride. The film itself is a lush palette of colour, texture and extraordinary use of light, as the relationship between the two women burgeons in a world where men have all the control, but interestingly (and refreshingly) scarcely appear on the screen. I met a surprising number of male critics who responded to the film even more strongly than I. With no soundtrack except for two stunningly beautiful musical numbers, Portrait makes for fabulous festival fodder.

Opening night at the Civic promises to be a joyous affair. French film La Belle Epoque may have been neglected from competition at Cannes but will have pleased more crowds than the festival’s actual opening film choice (Jarmusch’s lacklustre The Dead Don’t Die—purists may as well see it when they can, but don’t say I didn’t warn you). La Belle Epoque’s conceit is delightful, but its execution is what raises “imagine you could go back in time to a significant moment” to ecstatically energetic and enjoyable heights. I thought I had grown weary of Daniel Auteuil’s schtick in recent years, but here he is wonderfully empathetic as a man on the verge of a later-life breakdown. The story zips at pace between two sets of lovers, both struggling to make it work in their own way, and the script zings with bright observations and genuinely laugh-out-loud absurdity.

Sorry We Missed You

It would hardly be a film festival without Ken Loach, and while I feel a little jaded by the recurring line-up of apparent Cannes faves who appear on each year’s Competition list, 83-year old Loach never loses his touch. As usual, Sorry We Missed You tackles big, universal issues in a small, local setting, as a working-class family struggles to make ends meet. I can’t say the story is shockingly fresh, or even that the performances are pitch-perfect (Loach continues to use budding actors alongside newcomers, often to incredibly impressive effect, but inevitably some moments feel more staged than others)—and yet, somehow the unpretentious truth and his dedication to realism always manage to leave you devastated and pensive by the end. As powerful as I, Daniel Blake, this latest Loach is a must-see.

Some of the splashier films at Cannes were sufficiently diverting but, for me at least, problematic in some way—such as the Chinese noir thriller The Wild Goose Lake. It’s genre fare in the extreme, with all the noir tropes present and accounted for (gorgeous lighting, surly taciturn men, pelting rain), with some startlingly violent set pieces thrown in for luck. While I didn’t connect with the protagonists as much as other viewers, the simple plot of a crim on the run and the girl who gets entangled in his restricted freedom garnered excited raves at Cannes, and even enticed Quentin Tarantino to gate-crash its premiere. (No doubt he loved it.)

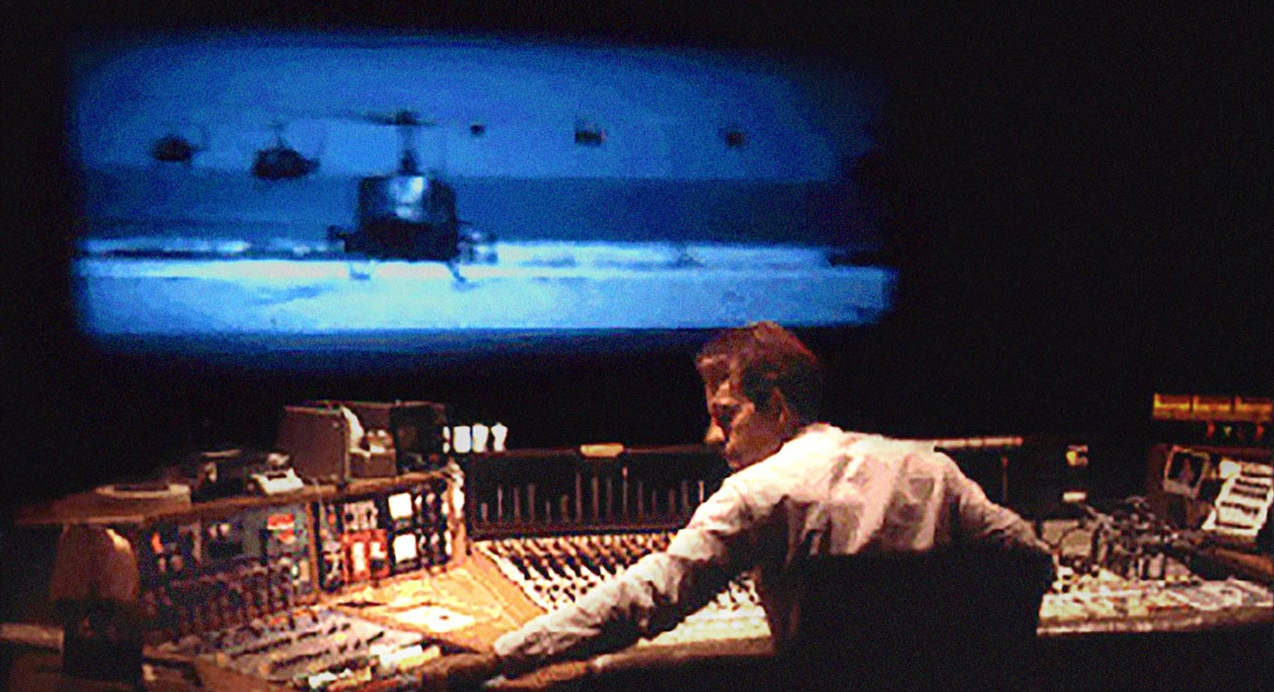

Completely un-splashy and a million times more exhilarating, the documentary Making Waves: The Art of Cinematic Sound is a fascinating and educational journey behind those Dolby speakers and into a world of unsung heroes who actually give you that amazing cinematic experience without your even realising. Even before the opening credits rolled, the audience had burst into spontaneous, ecstatic applause, and thereafter director Midge Costin (a sound designer in what turns out to be an industry surprisingly peopled with women behind the scenes) delivers a dissection of sound design and interviews with those who appreciate its value which will ensure you never hear a movie (including a well-examined Apocalypse Now) the same way again.

Making Waves

For something completely different from all of the above, take some time out with Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman’s It Must Be Heaven. A series of scenes rather than a narrative flick, Suleiman travels to foreign climes and observes, often with absurdity and affection, some strange aspects of humanity. Those familiar with Suleiman’s Keatonesque deadpan visage will already know if they find him charming or not (I do), so just go along on his journey, where the occasional snippet of dialogue or a sharply observed moment can deliver a telling point only too well.

Fortunate enough to have seen other offerings in other European cities’ festivals this year, I can also highly recommend Peter Strickland’s latest, In Fabric—a strange and beguiling tale of a devilishly murderous dress. Actually, that sounds sillier than it is—it’s actually a beautifully acted drama which yearns to be romantic and sensual, with terrific performances from Secrets & Lies’ Marianne Jean-Baptiste, I, Daniel Blake’s Hayley Squires and the most hilarious cameos by two of Britain’s funniest men.

When Agnès Varda passed away in March, all of France mourned. This isn’t an exaggeration. It was staggering to see first-hand how much a nation (granted, one with an internationally-renowned cultural heritage and a centuries-old dedication to the arts) banded together to celebrate the life of “the Grandmother of the New Wave”. Festivals and repertory theatres around the world have been pulling together Varda retrospectives, and NZIFF is no exception. If you’re a Varda newbie, you’re as well to start with her 1976 feature Daguerrotypes, a quietly observational documentary about the people living on her Parisian street, Rue Daguerre. Varda’s gentle, unassuming access granted her the extraordinary ability to paint portraits of ordinary folk from a very different time.

And finally, a two-thumbs-up approval for Francis Ford Coppola’s Final Cut (no, really) of the legendary Apocalypse Now. I thought I’d seen the previous iterations decades ago, but now realise my experience of the film, which feels deceptively well-trodden, merely extends to key scenes and eternally-repeatable but actually morally-reprehensible quotes like “I love the smell of napalm in the morning”. Coppola flew into the Il Cinema Ritrovato festival in Bologna last month to unveil his newly-restored, perfectly-recut masterpiece. Reinserting some of the “weird” stuff he’d originally been told to take out (and noting “today’s avant-garde is tomorrow’s wallpaper”) and showing discernment around the distended Redux, this is now three hours you’ll never want back. To watch it on the Civic’s big screen, with helicopters whirring in the remastered surround sound and sweat glistening on Martin Sheen’s nose, will be a special pleasure for cinephiles.