Animals director Sophie Hyde on her Dublin-set tale of female friendship

Animals tells the story of a young friendship at a crossroads. Director Sophie Hyde spoke to Steve Newall about her film.

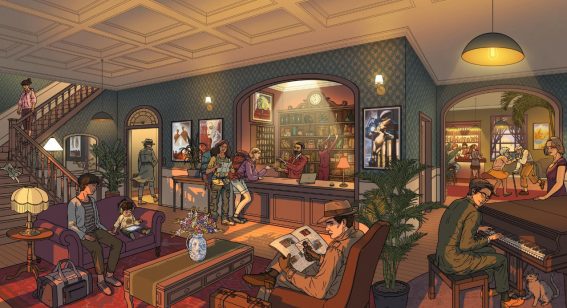

Holliday Grainger (My Cousin Rachel) and Alia Shawkat (TV’s Arrested Development) are best friends—and committed drinking buddies—whose relationship is pressed to evolve in this dramedy based on Emma Jane Unsworth’s novel. As the NZ International Film Festival programme notes “it is in the empowered female sexuality, with the male characters playing second fiddle, that Animals truly shines”.

Sophie Hyde was in New Zealand as a guest of the festival and sat down for a chat with Flicks.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

FLICKS: What was most relevant to you about this story?

SOPHIE HYDE: When I read the novel, I just felt there were two women and a friendship and also kind of romantic relationships that felt like they were very familiar to me. My feeling of it was that they were very kind of present, physical relationships. I didn’t feel like I was really seeing that.

I felt like, particularly in stories about women, there was a lot of stuff that was Girls Gone Wild/Mums Behaving Badly kind of vibe and then it was kind of very saccharin on the other side. And to me, friendships with my girlfriends felt a bit more difficult than that. A little bit harder to place. And that, of course, is a challenge then to put on the screen because it’s not simple. And so it’s like, “How do you find those elements and tell them in a story?” Create a story that will satisfy that isn’t just totally conventional.

It’s interesting to watch that relationship brought to life with individual characters who are trying on personas at that stage in life. And even in the context of such an intimate friendship watching them do that with another to an extent.

They’re very performative characters. They perform their role, and they’re kind of playful with that. And so some people really relate to that I think, and other people feel distanced by it. But that kind of armour that they put on, or the kind of characters that they put on even amongst each other, particularly at the start of the film, is very strong. And because we see the story through one character’s point of view, when she’s seeing the other in that performative way, we are as well. And as that starts to break down, we start to see a little bit underneath her armour.

Some of those rituals and shared things in the friendship start to fragment a bit.

Yeah, that’s right. Because you do have these roles that you’re playing. I mean, for me, that was the story. It was you can get stuck in anything. And some people get stuck in their job and whatever. But these girls, they get stuck at the party, I think. Particularly Laura [Holliday Grainger]. She gets stuck somewhere. And when you’re stuck, you repeat stuff. And you think you’re free and having a good time but you’re actually a bit bored [laughs].

You kind of don’t have that perspective until you stop doing it.

Yeah, I think so. And I think we sort of know… you feel it. You have moments all the time. It’s not like one big revelation, is it? People always say to me “It’s like coming of age, but they’re older.” We don’t just come of age once and then we’re adults, ourselves as set creatures. We’re kind of constantly coming of age or shifting into different seasons of our life, I think. So Animals is really looking at that idea.

It’s probably simplistic to say, “Gosh, it’s a really important relationship on screen, so casting must have been very important” because casting anything’s very important. But how was that process for you of finding your leads and making sure the chemistry worked?

Chemistry’s a really interesting thing. I mean, my belief is that good actors, they create chemistry. That’s their job. And my job is to help them do that. It doesn’t always work, though. But I do think it’s their job.

You do have fear in this sort of thing—we cast these two women and they’ve never met. We didn’t do a casting test—a chemistry test—or anything. So there was always a little bit of trepidation around that. And how we went about it, the book was originally set in Manchester and we cast Holliday when we were still planning to shoot it in Manchester. She’s from Manchester, so she had a really strong connection to that world. And when we moved it to Dublin, we had a long conversation.

I love Hol. She’s very vulnerable, interesting kind of actor. I think that lots of things play out for her. She’s very smart. And I’d seen her so much in period drama stuff. She’s often in a corset. She’s even quite grounded in all of that. But we see her as a kind of English rose a lot of the time, and I really liked the idea of seeing her play a character closer to herself, which was modern and interesting and sort of rejecting a little bit of that artifice of those kinds of movies.

And Alia, I’d always seen her in loads of indie stuff. Arrested Development and all those indie films. And she was always a bit awkward and whatever. She played that character. And I think Tyler’s a very cool character. Very performative, as I said. And I thought it was wild to see that. We had a Skype, Alia and I. She said to me in the middle of it, “Bloody hell. I get really annoyed by couples. They’re always sitting there being couply together.” I thought, “Oh my God. You are Tyler”.

But I’d never seen anything like that from her. I think I wanted to see two people in those roles that felt a little bit surprising and that together they felt surprising. And they were that. But of course, there’s always a risk that that won’t work. And the girls came together so well. We did loads of work. We did lots of intimacy exercises. I sent them off on tasks around Dublin getting to know each other. Getting to know the city. They met the other characters kind of together. They just did stuff together that gave them a shared history, I think. And that really helped.

How come you ended up in Dublin rather than your original setting? Pragmatic production reasons?

Firstly, it was pragmatic. We couldn’t raise the money out of the UK. And I was surprised because it seemed like a very financeable film to me. And there was a suggestion that we could potentially raise some money out of Dublin. We were already planning to do a co-production with Australia, so that was already in play. And we sort of went there like, “Okay. Are we going to shoot Dublin as though it’s Manchester,” like fake it, or are we going to sort of make it a more generic city, or will we do Dublin?

Getting there, it was a no-brainer really. I mean, it’s this very literary city. Drinking and drug culture is very strong, but there’s poetry on every corner. And also, it’s very political. We were there during the repeal of the Eighth Amendment vote, which was about abortion rights. And so there was this whole conversation about women’s bodies and whether they had control over their own bodies. And so it felt very much like the right place to tell the story.

Then, the city kind of transformed the film a little bit. Because the book’s very set in Manchester. Manchester’s a character. It impacts on who the women are. Therefore, Dublin did as well. Dublin kind of changed the way that we did the poetry salon and the visual style of the film and that changed the costumes. So it feeds in. It has to, really. You could do it in Auckland or Wellington maybe.

Have there been any surprising or standout audience reactions to seeing the film?

We thought it was directed at a youngish audience. And certainly, 30-year-olds are very strongly connected to the story as though it’s their story, of course. Both Emma and I are the same age, which is a bit older than that, and so we think of it in a kind of nostalgic way.

So you’ve got perspective on all of that stuff, right?

That’s right.

But the characters, or people their age, might not so much?

A lot of that age group are like, “It’s a bit close to home still.” What surprises me is that people have a very emotional response to it. It’s like, “I had a cry.” Like, “I’m not sure how I feel.” And people expect to go in to have a really good time [laughs]. And I think they do, but I think it hits something for some people, do you know? That’s great, but it’s not exactly what you go for.

You want people to feel things, but people feel things about themselves in a strong way, I think. And also everyone thinks it’s for young people but the number of times quite old audiences—both men and women—come up to me and say, “I love it. I feel like it’s me.” They have really a very, very strong connection. And my feeling is that because it’s very much a subjective film that’s told from one person’s point of view that means as an audience you can sit with it. You identify more than you might with some films.