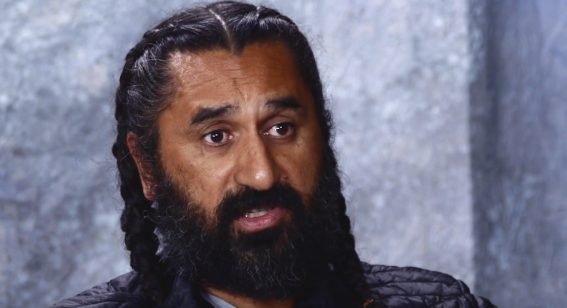

Ant Timpson talks us through his equally touching and disturbing Come to Daddy

“Watching Dad literally drop dead in front of me was the turning point”.

After decades of his impact being felt on film culture in Aotearoa—and increasingly internationally—Ant Timpson has made his directorial debut with Come to Daddy, in cinemas here February 20. Elijah Wood stars in the film as wannabe music impresario reuniting with his estranged dad, and as you’d expect from Timpson, the film goes to some… interesting places. He talks us through the film’s tragic inspiration, the pressure of making it, and plenty more—including the unexpected positives of stuffing up a scene on day one of your movie.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

FLICKS: You know as well as anyone, having curated films from decades of different epochs of cinema, that movies last forever. Did you feel your balls were on the line making your first film as a director?

ANT TIMPSON: Yes. I felt everything was on the line because of how long it’s been since I first had an inkling of wanting to do this. And then, also, once it became a reality that it was going to happen, then just an enormous, ridiculous amount of self-involved pressure being put on myself to make sure that it lived up to my expectations, which were ridiculously high. So yeah, I instantly felt a huge panic about the whole thing. I feel you need that, actually. If you don’t have that, then you can’t be human, I don’t think. I don’t know about the panic, but the pressure is always going to be there no matter how many you’ve done, right? I firmly believe that. It’s never a ride in the park, as they say.

I was also in kind of my little world down here, when it was just me and the writer I was working with. And it just changes once more and more people physically get in around your space, because you internalise everything. You’re in your head, which is sometimes the worst place to be. So once the reality is staring at you, then it’s better to be physically around more and more talented people and then you feel like your job is really to pull them into what the vision is. And the more adept you are at doing that, yeah, the better it starts feeling.

For people that aren’t super familiar with your overall background, perhaps you could give the readers some insight into when you first started playing with film and making stuff and how long a journey it’s been to actually get to this point.

Well, I’m old enough that I should have probably been the film-obsessed kid playing around with Super 8, but I wasn’t that. I feel that’s particularly a New Zealand experience, apart from Peter Jackson—I didn’t see a lot of Super 8 bouncing around when I was young. But I was one of those home vid kids, who once the first cameras came out, the big beasts, was proceeding to kill my brother, Matt, pretty much every weekend as well as other assorted friends and just having a huge amount of fun creating on that level. And around that time, a bit earlier than that, I used to write a lot as well, write short stories and send them to friends. So I always had that kind of creative desire—I don’t know what it is, but it’s a need for people to respond to the things that come from a place of purity, I guess, inside of you.

That led to me wanting to work on films, which I ended up doing, and then screening films when I went on to manage Charley Gray’s Cinema. And then I got into distribution, buying films like Slacker, and then actually ending up producing things [like The ABCs of Death, Turbo Kid, and The Greasy Strangler], starting the genesis of ideas with other talented folks and then following it all the way through. I kind of ended up in all the facets of the industry, but I took a path away from filmmaking and just became super busy with [annual filmmaking competition] 48Hours and the Incredibly Strange Film Festival and producing.

I was still that obsessed kid who wanted to create a film and had dreams about making a feature film. But I got comfortable, and I needed to be shaken and woken up. And watching Dad literally drop dead in front of me was the turning point of staring mortality in the face and all that combination of childhood dreams and everything starting to, well, shatter the comfortability that was surrounding me and then realising that life’s really short. I need to get out there and make something.

I knew the impact that your dad had on the narrative idea, but I didn’t realise it was such a pivotal catalyst of this thing happening, full stop.

Absolutely. I think it’s highly recommended as a catalyst, watching someone drop dead in front of you. It really kicks your A into G. So if you’re needing any inspiration, man…

Wow. Once you dealt with everything you had to deal with privately through that, did you quickly start putting some things in motion and try to get something up and running?

It’s a little bit blurry now. The body wasn’t still warm. Let’s just say that. But it felt pretty quick after Dad’s passing that I wrote to Toby Harvard, the writer, and said, “I really feel the need to get something done.” Eventually, it became like a tribute to Dad. They’re the type of films that I loved growing up, watching with him, and the whole sort of gallows humour was part of our coping mechanisms we had through it with our family for a lot of stuff. So that was kind of inherent in me, and Toby shared that sensibility, wicked sensibility.

What are some examples of that stuff that you’d watch with your dad that epitomised that gallows humour?

A lot of television, really. Like the early Roald Dahl, Hammer House of Horror, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. I feel like the first round of that sort of material. And film-wise, it was those moments like Get Carter, those things that were kind of dark thrillers, but there was always characters that were off-kilter and dark. It was the tonal stuff that crept into other thrillers that I was growing up with.

A film like The Taking of Pelham One Two Three, which is really a gritty in-your-face thriller, but Walter Matthau elevates it with his performance and his character, which is super dry and darkly funny. And there’s a sort of mortician’s sort of glee to a lot of the proceedings later on, especially with Robert Shaw. So yeah, I mean, if I sat down and thought about it, I could probably write a super long list of films. But it was more just a sort of gut feeling of the way the tone goes to those places within a sort of straight and narrow.

I think particularly of the shows that you mentioned, so many of those episodes are about established tone and then swerve, and that’s something we see really effectively in your film.

Yeah. And some of them were truly dark, especially the Roald Dahl stuff. We’re so used to kind of the more wry stuff and droll, dry humour of his, but then there was some super dark stuff that I remember… Really dark, yeah, really dark and creepy. But like with most things with nostalgia, you don’t want to go back. You just want to retain those memories and work with them instead of rewatching them and destroying it.

If you sat down with no time pressure or sense of urgency, how different do you think the creative process would have been? Would it have been a nightmare?

It wouldn’t have happened, I don’t think. I mean, I honestly don’t think the film would have kicked into gear. I wasn’t looking actively or looking at scripts to make. It had to come from a personal place. Otherwise, yeah, I would still be back doing what I was doing two years ago or whatever. It needed to be some sort of nuke going off to shake the cobwebs, pretty much, of where I was at. But now I’ve tasted it, it’s like the blood’s running to new areas of the body, so to speak.

You’ve avoided what a lot of people do on their first outing, which is try and put every single idea they had into something.

The one thing I think I’ve got is that I feel like I know what’s in that world of that type of film that I was making. And so we didn’t want to overcook it. We wanted to have fun. I knew where things go wrong. I’ve seen so much that I kind of inherently have to rely on gut instincts a lot of the time to make sure to not go off that. And I sometimes think people don’t have that ability to believe in themselves and sometimes dilute it by taking a safer route or by letting more opinions come in and sway them and not being confident enough with the material that you set out with at the very start. I mean, there’s just a natural degradation of all filmmaking. The process itself can be chipped away slowly throughout just making films. And I guess any art suffers from it unless you’re just doing something, painting in your room or creating a song. Films, there’s so many parties involved that sometimes it’s a miracle that anything comes through and retains the purity of the original vision. It’s extraordinary how it all works out sometimes.

For something that started in such a personal place, what was it like to see those ideas kind of be redirected from where you might have expected them to go?

That just disappeared once we got stuck into it. And you just get swept up by the filmmaking machine, it’s a runaway train, and you’re on it, and you’ve just got to go with it. And you don’t have time, really. I didn’t feel like I had time to remember the sort of points until right in the moment of it happening in front of your face in the frame, suddenly realising, “Oh, yeah. That’s right. That’s in the script because of this moment that I had.” It started having some emotional heft, whereas it was really just out-of-body, bigger picture for a lot of it until those key moments that were from a very personal, real space. And then you get suddenly pushed back into that, yeah, where it all came from. And hopefully, the emotional weight that it’s got for you is somehow subconsciously working with the audience, if we haven’t danced on that high wire too much.

I can completely understand how you’d kind of come crashing back. One minute, you’re in a very frantic and kind of theoretical space, and then, as you say, it’s right there in front of you.

Yeah, because there’s so much going on. There’s so much detail that you’re constantly asked about by every single area of what’s happening in the frame, which is a lot of things going on. And so it’s having that ability to do all of that and then focus on what is actually the core idea of what each scene is happening. And it took me a while, honestly, for it to start all running beautifully for me. I totally was like, “Holy shit.” At day one, it was just like, “It’s full on.” But we knew that was coming, and I worked with a small core team to set it up, so we didn’t hit the ground doing super complicated stuff. We kind of eased into it, and it was all planned to make it a nice smooth transition. And I’m glad that we did plan it out that way because it can feel overwhelming straight out the gate.

I think the whole thing has made me feel like I would be a much better producer [laughs] in the future. You think you know what they’re going through and what they’re feeling and what your crews are feeling. But yeah, it’s intense. And you’re so protective, and you feel like you’re against the wall the whole time that the natural instinct is to come out swinging and fight for everything, when it’s way better to be like Bruce Lee, be like water.

Can you paint us a picture of what that first day was like? Where were you geographically, and where were you in the timeline of the film?

We were super lucky. I mean, it was going to be a winter shoot originally in the very upper northwest of Canada on an island, and so it would have been brutal. But it wasn’t. It turned out we got bumped, and it became a summer shoot—which ended up being great because we’re so used to seeing those traditionally stormy, very dour atmospheric sort of one-location, two-hander chamber pieces. I’ve seen that film. So I was kind of happy that it made the switch, and we had more of a palette range to play with and more of a juxtaposition in terms of contrast of the type of film it is. It’s a thriller, but we’ve got these beautiful, poppy, bright surroundings.

So, day one, it was the greeting scene of when the main character meets his dad at a very remote location. We literally filmed that, him walking up, knocking on the door, and them embracing. It seemed like an easy one to do, even though I completely ballsed up the gag that actually happens in that scene, which doesn’t exist anymore. But it was because I was just completely in the space of watching these two people bounce off each other and trying to think like, “Is this working? Is this working? Is this working?” that I completely missed one of the gags that I was supposed to cover.

Once I realised I missed it, I was like, “Shit. We don’t have pickups. You don’t get redos. You can’t rewind. This is it.” So it was kind of a great start in a way that it started easy—and I still missed something. I realised, “Okay. You have to be on the ball every second and make sure you’re super prepped and mentally don’t get overwhelmed. Keep that list just for this moment in time.” And that’s why it was really good to have someone like Elijah, who’s so savvy instinctually of how and where he needs to be in that moment in terms of camera placement, everything. He’s just a joy to work with. And having a communication between us made it a real breeze because we worked together so much in this film. He’s on-screen every single frame.

That first day was kind of a joy. At the end of it, I felt exhausted, but also I felt like, “Okay. I can do it.” The fear went away, basically, I didn’t feel afraid anymore.

There’s alchemy involved in filmmaking. You can never control everything. And a lot of time, these curveballs actually turn out to be for the best. If you set up with a character walking through stormy weather, going to see someone that he has a very dark reunion with, then it’s like you’ve laid out all your hand straight away. So things like that were great. And the location itself is gorgeous. I walked to set each day. I spent a lot of time with a small crew, the DP and producers, there for six weeks just prepping and getting it all ready.

So I felt super confident with the location. I knew that house that we went to inside and out. And I’d done schematics and worked with the writer in tweaking the script to make sure there’s a logic to every place in the whole narrative. And so, I felt very confident just being there, living there, and breathing it all in.

The only sort of nervousness I had on that first day apart from just like, “Is it going to feel right in the frame?” was with Stephen McHattie, who’s just a legend and quite intimidating an actor, who’s been doing it for 50 years, who’s worked with everybody in the business. Super stoic, quiet guy, not an oversharer. I’ve seen some stuff where he destroyed journalists on the red carpet just through withering glares and silence. I was kind of prepped for him. We had a staring contest when we first met, and it was super awkward. And I was like, “Well, if I’m feeling this way, I know Elijah’s probably going to feel the same way, and it’s going to come across on camera.” And I felt really good.

Even though he turned out to be like a sweetheart, it was kind of essential to have that really sort of uncomfortable distance between us and also between the actors. So it worked out well. Plus, physically, for an old dude, he was kind of menacing, man. He was dropping down and doing 50 press-ups between some takes and things. So he could’ve kicked our arses.

And you know, you get lucky. You have these ideas for a cast and everything, but it’s super rare that you end up with who you want from day one or whatever. Films just don’t work out like that. It’s very rare unless, I guess, you’re Tarantino or Scorsese. But for us, I can’t imagine the film now with anyone else, which I think is a cliché. But I honestly think some films can get overwhelmed with who they put in. And I just feel like we did the balance kind of perfect, and it really, really helps the film.

Tell me a little bit about developing Elijah’s character and aesthetic.

Toby, the writer, he bases a lot of his characters on personalities he bumps into. He’s like a real sponge. And he writes so well that he can kind of flesh it out in your head. And we all had similar sensibilities, so we were all on the same page. I kind of wanted a particular type of vibe, and it would have been very different with different actors, to be honest. I knew Elijah is an inherently likable human being and has such goodwill with the audience that his pretentiousness and everything douchey about the guy won’t matter. The audience will have empathy with this guy because I know how good Elijah is in grounding the whole film. I could imagine this film possibly miscast, and people just hating him—not even bothering, wanting to go on the journey with the main character. And that would have been a very scary trip to go down.

I think he brings a sympathetic fragility to the douchiness that other actors wouldn’t have.

He’s drawing on similar things with him and his dad, and so there’s a real honesty to it. And he completely realised that a lot of the posturing that the character does is really just this desperate need to want to be loved and to connect with a parental figure, which everyone can relate to. So there’s a very human association that the audience makes with him. And no matter how much he talks about hanging out with celebrities, they want it to work out for him.

It’s been a while since this film first played to audiences. Has the way you view the film changed over that time? And what’s it like still doing press and introducing people to it for the first time?

It hasn’t really changed. There was a period of time where I was watching it with audiences. And then I had a big break from it, which I think it’s just a natural occurrence for most filmmakers with their work because they reach saturation point and they just don’t want to even look at it for a while. So I’m kind of in that zone. But no, it doesn’t change because during the edit you pick it apart every which way but loose. And there’s amazing, cool little details that I know no one will ever get except myself and maybe two others, and there’s one that I know that no one knows. And there’s things like that that I’ll always find amusing.

But yeah, in terms of introducing it, you do have to watch yourself because if you sound bored that you’re going through the motions of saying the same thing you’ve said 100 times, then you’re not really setting the audience up very well to appreciate it if you sound like a frozen monotone record. I also bore the hell out of myself hearing me talk about it, so I try to find different angles, to be honest.

People hate Q&As because—well, they hate audience Q&As—because there’s always someone saying, “How do I get into the industry? Do you want to read my script?” or something ridiculous like that. But I actually think the audience curveballs are where it allows the filmmaker, who’s talked about the thing a million times, to get something crazy to spice it up a little bit. Otherwise, you really do feel like you’re just walking on a treadmill doing the same thing.

It’s a film that’s going to have a specific, niche audience.

Ooh, yes.

Does that give you a certain security or temper your fears about how it performs when it’s out in the wider world?

I know it’s going to find its audience primarily on video on demand and streaming. It’s real tough in the theatrical world at the moment for these sorts of films. So yeah, luckily, I come from a background involving distribution and exhibition, so I’ve got very realistic expectations of the film. Luckily, though, I’ve been knocked out by the response it’s had all over the world. I couldn’t be happier. I mean, it’s a win now. It could explode overnight, and I’d still be super happy.

That’s great to hear.

I mean explode into nothingness.