Barry is as funny as ever in its final season – and much, much darker than when it started

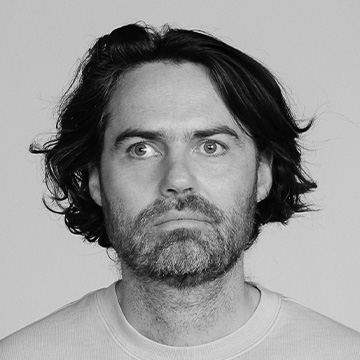

Bill Hader’s Hollywood hitman is back in the fourth and final season of superb black comedy Barry. Tony Stamp is full of praise for the increasingly confident and challenging direction the show’s taken since its debut – and where it’s going as it heads into its home straight.

When Bill Hader’s HBO show Barry launched it was surprising inasmuch as he played it pretty straight. A dramedy about a sociopathic hitman who gets bitten by the acting bug sounded like a recipe for broad comedy, but the results were darker than you might expect from his outsized comedic persona on things like Saturday Night Live, and the gags tended toward wry chuckles rather than belly laughs.

As the seasons progressed, the show evolved away from its sitcom-level conceit and allowed the plot to propel its characters wherever they landed. By season three it felt like Barry had found itself, echoing crime shows like Breaking Bad alongside pitch black comedy, with multiple plotlines delving into the world of showbiz as well as various crime syndicates.

Hader had directed eps since the beginning but he upped his game in the third, displaying a remarkable eye and unique style, and in the show’s final season he’s truly found his voice. And Barry has reached its final form.

It’s shockingly bleak, often mean spirited, and moves at a clip through its multiple strands as they begin to coalesce. It feels like the work of a filmmaker free to do whatever he wants, and the results reveal a massive well of cynicism under Hader’s sunny exterior. Lest you be put off though, I’ll note his sense of how far to go without alienating the audience is spot on—when all is said and done it remains a non-bummer.

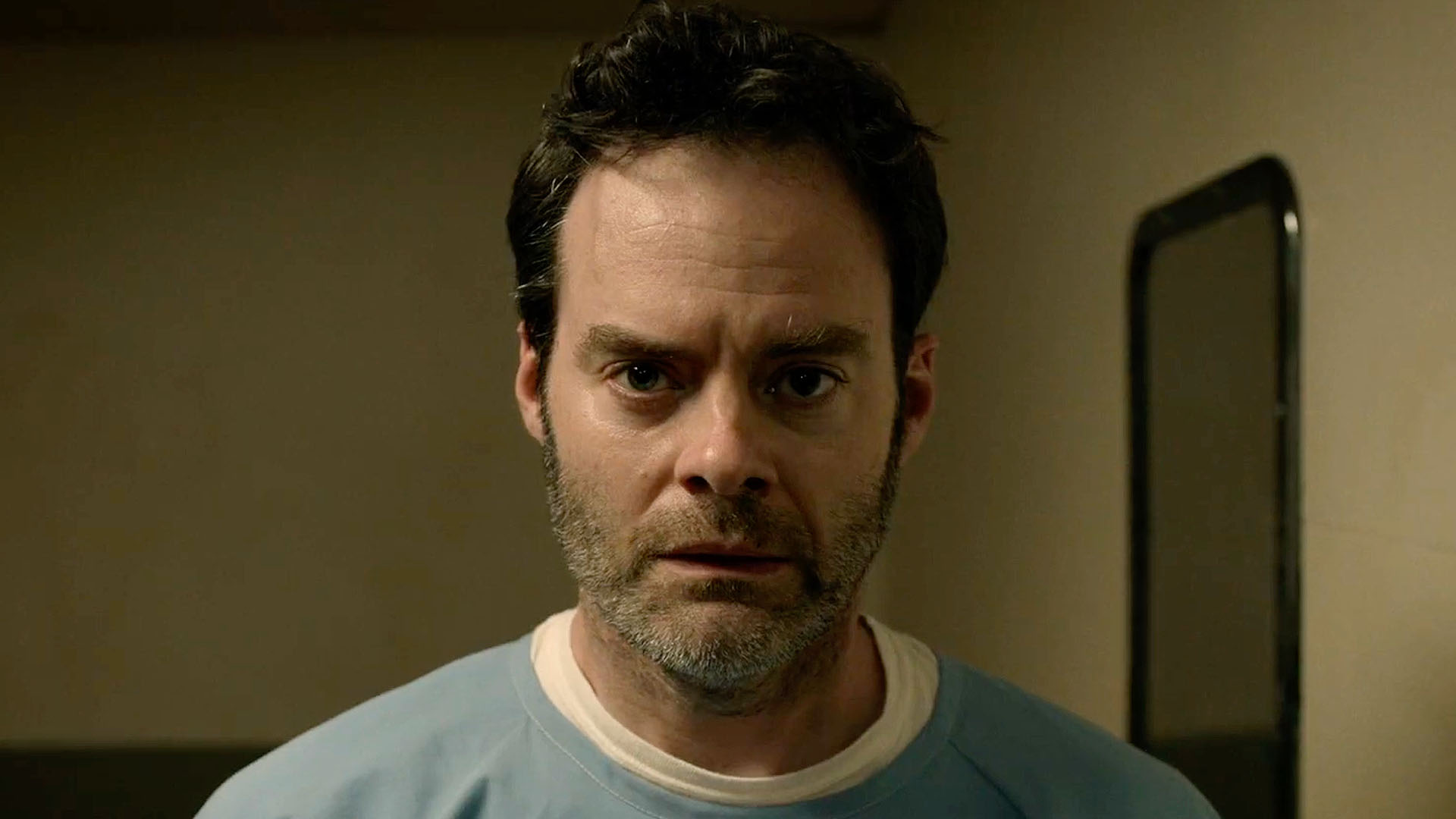

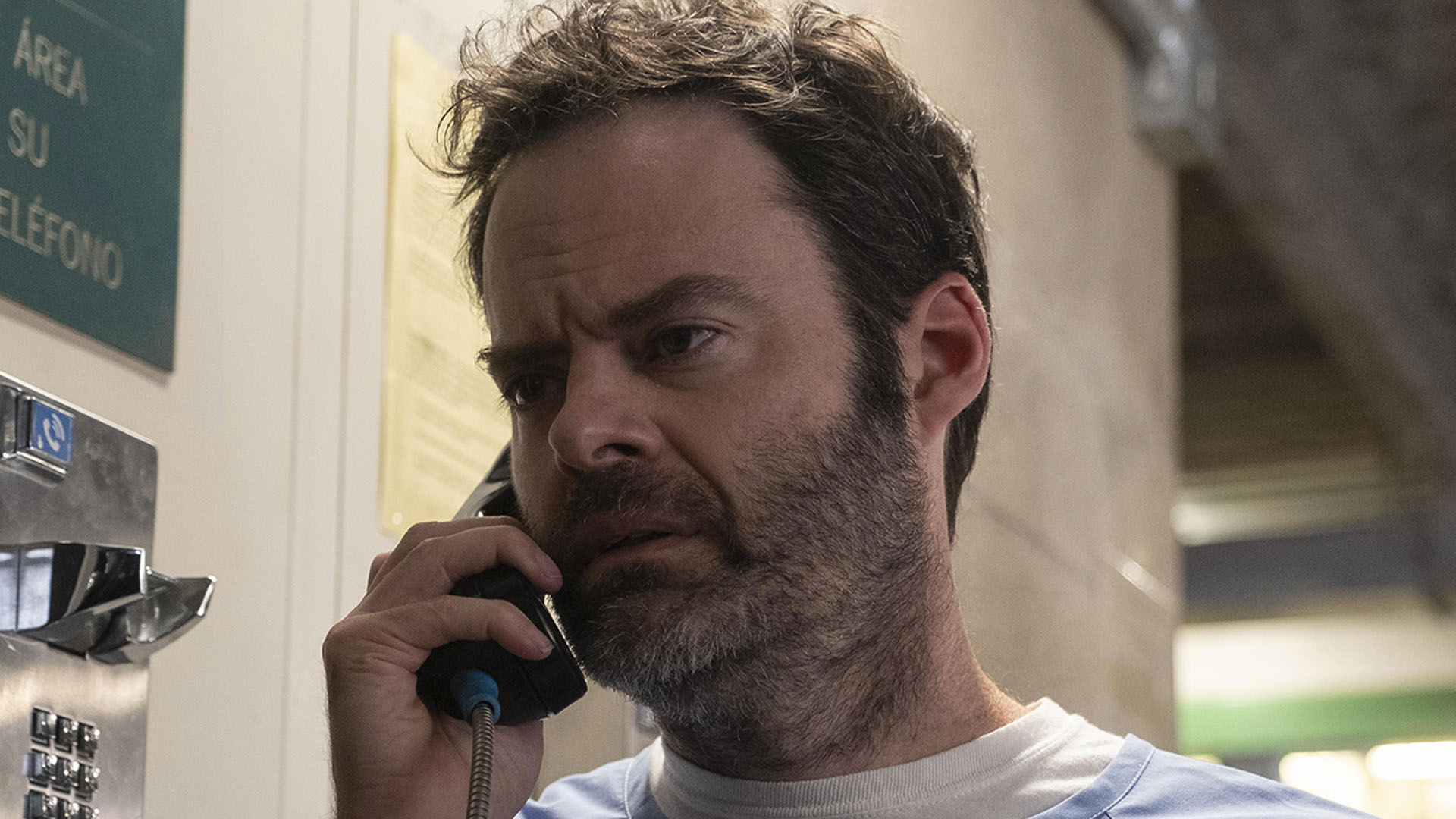

The characters though, are extremely bummed. Barry himself is in prison on suspicion of being a serial murderer, which he is. He’s lost his girlfriend Sally, who he met in an acting class and whose life was subsequently infected by his predilection for violence. Even before that he was screaming at her in front of her colleagues. Oh and her prior boyfriend was abusive too.

Sally’s plotline is illustrative of the whole show: the situations involving domestic abuse are appropriately horrifying and treated as such, and she’s no doubt a product of circumstance, but at the same time Hader and his writers recognise that without that context, other people just find her awful. The way that’s mined for dark humour is daring, and Sarah Goldberg is better here than she’s ever been.

Her story is a microcosm of Barry’s nature/nurture thesis, which applies to the title character’s journey from army veteran who killed an innocent through to his current state as someone who will pretty much kill anyone. Each character has changed since the show started, and they’re about to change a lot more.

NoHo Hank began as a joke, a seemingly oblivious member of the Chechen mafia who over the seasons found love and became one of the most sympathetic characters. Of course, he was then put through the wringer, and the end of season three found him chained up in a Bolivian cell listening to his comrades being eaten by a panther in the next room.

The way this scene played out, locked on Anthony Carrigan’s horrified face, spoke to both his skill as an actor, and Hader’s savvy behind the camera. More on that soon.

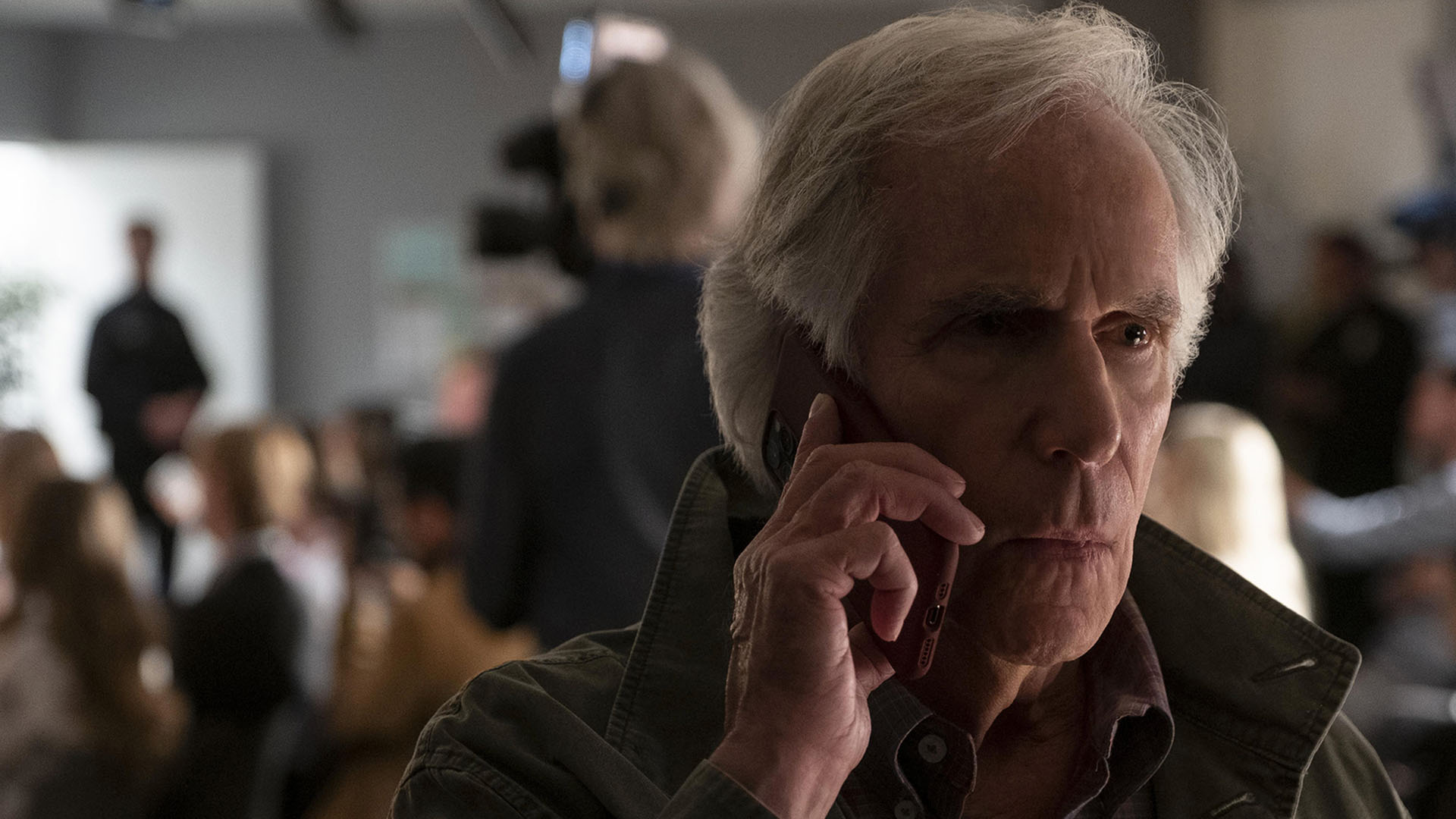

As this season begins, Gene Cousineau has tricked Barry into being arrested, avenging the death of the woman he loved. But even in triumph, he’s too narcissistic to stay out of trouble. Henry Winkler, gifted an Emmy award-winning role that swings from goofy to hugely sympathetic (often on a dime), makes the absolute most of it. It’s great watching him sink his teeth into something all these years after The Fonz.

And Stephen Root’s Monroe Fuches might be the most complex character of all. It’s revealed early on that he’s known Barry since childhood, which goes some way to explaining their dad/son bond. Now that Cousineau has betrayed him, Barry is missing a father figure, and it makes sense that Fuches may reclaim that role.

Because after everything he’s put Barry through, all the ways he’s manipulated him into doing terrible things, he does still seem to love him. Like many of these characters, some of the worst things Fuches has done can be explained by simple stupidity, and season three revealed there’s still some humanity left in him. It also gave Root one of the funniest sight gags of the show about halfway through the season, an extended sequence I absolutely won’t spoil.

No one here gets off easy. There’s no one to root for anymore, and they’re all punished (torture of various kinds abound). The first episode has Barry taunting a prison guard into giving him a beating, and things just get more grim from there.

And yet there are laughs too. The direction is going to get talked about a lot, and seems like Hader auditioning for a feature gig, which I dearly hope he gets. A lot of humour is smuggled in visually: action in the background that characters in the foreground aren’t privy to, slow pans to things you weren’t expecting, something silly next to something very bleak.

He’ll often lock off his camera in a wide shot and linger for a long time, letting the action and his performers dictate the scene. The sense of remove, like watching ants under a glass, brings to mind Stanley Kubrick, or even recent Nicolas Winding Refn, and numbs some of the discomfort in favour of the absurd.

Hader has said many times that he’s always wanted to direct, and when guesting on The Ringer’s Prestige TV podcast is relatively humble in how he discusses it, saying he wanted “one visual language for the whole thing” and tries to get “all the information in one shot”, framing these choices as practical rather than artistic. Meanwhile on another Ringer podcast called The Watch, they drew comparisons to Fellini and Truffaut.

The praise is warranted, as Hader repeatedly deploys visual language that’s as complex as the show’s characters or its tone, weaving between comedy and tragedy with an uncommonly steady hand. It’s only gotten better as it’s progressed, becoming knottier and more confident. As it approaches the finish line Barry is as funny as it’s ever been, and much darker than when it started. We’re guaranteed one hell of an ending.