Before sickeningly sweet Amélie was the sweetly sick Delicatessen

Surreal, post-apocalyptic black comedy Delicatessen was the 1991 debut of director Jean-Pierre Jeunet. Amelia Berry revisits Delicatessen‘s dark surrealism – and finds there might be more in common with Jeunet’s later film Amélie than one may expect…

In the 2000s, Amélie was an inescapable force. It was just as likely to be found as a poster in a student flat, as to be one of the five DVDs in your mum’s DVD collection. Teenagers around the world got Amélie haircuts, listened to the soundtrack of Amélie on an iPod Nano, and ran their hands wistfully through sacks of grain. Coming out right at the end of 2001, its release announced a new cultural force, one of quirky introverts in cardigans playing the accordion in berets.

But Amélie had a secret past that only very few know about. While everything might have seemed sunshine and lilacs on the surface, lurking somewhere in the shadows was murder, kidnap, infidelity, and even… cannibalism. No, this is not Amélie Poulain fan-fiction. It’s director Jean-Pierre Jeunet’s 1991 debut feature Delicatessen.

Co-directed with Marc Caro, Delicatessen is a post-apocalyptic black comedy set in an apartment building at the end of the world. Clapet (Jean-Pierre Jeunet) is a landlord and a butcher. In bomb-blackened near-future France, the only meat available is from the handy-men Clapet hires and then murders. But when the new handyman, ex-clown Louison (Dominique Pinon), falls in love with Clapet’s daughter Julie (Marie-Laure Dougnac), things quickly get out of hand.

In amongst the blood and gloom though, are some memorably weird characters. Longtime Jesús Franco collaborator Howard Vernon plays ‘the frog man’, who lives ankle deep in water, surrounded by frogs and snails, wearing little ping-pong goggles and killing flies with a party blower. Then there’s the resistance, the vegetarian Troglodistes who seem to be exclusively male and live in the sewers dressed in flapping rubber suits.

From the pair of men painstakingly assembling ‘moo boxes’ (those things that make a weird noise when you turn them upside down) with glue and a drill, to the extremely prim woman hell-bent on killing herself in the most elaborate manner possible, everyone who lives in the apartment building feels like a perfectly realised caricature, a charmingly grotesque cartoon.

The cartoon sensibility pervades the visuals of Delicatessen too, the set-design, costumes, and cinematography combining to create a bug-eyed dingy surrealism straight out of French comics (bandes dessinées). Co-director Marc Caro is himself a comics artist, and looking at his work it’s easy to see how the expressionist perspective distortions and exaggerated physicality have translated onto the screen. A pretty remarkable feat for a film made with such a small budget.

On one level, it’s all very early 90s. The alt-comics-meets-Terry Gilliam visuals, with a hint of heady art-house à la The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover. The comedic sensibility that sits somewhere between the Coen Brothers’ Barton Fink and Tim Burton’s Edward Scissorhands.

Watching it now though, it’s hard not to see Delicatessen as ahead of its time, the way parts of its visual language seem to have informed a whole thread of dark surreal sci-fi.

1998’s Dark City, while obviously also owing a debt to Gilliam, feels so specifically Delicatessen in its soot dusted tenements and grubby mid-century interiors. Bong Joon-ho’s 2013 film Snowpiercer also feels like it owes something to Jeunet and Caro in it’s dark but goofy social satire. The use of colour and exaggerated sets in Guillermo Del Toro’s Nightmare Alley and The Shape of Water both feel indebted in some way to Delicatessen.

And it was a successful film. Not successful like Amélie, but it did manage to pull just over twelve million dollars on a budget of just under four. It also managed to garner the pair enough acclaim so that their next film, The City of Lost Children (with a great lead performance from a ginger Ron Perlman), managed to snare Angelo Badalamenti for the score and Jean-Paul Gaultier for the costumes.

After that, the pair split. Jean-Pierre Jeunet went on to do Alien: Resurrection in 1997 and, after that, Amélie. And putting the story like that, it’s tempting to say that after Caro left, there’s some kind of fissure in Jeunet’s filmography, some unbridgeable divide between scary Delicatessen and sweet Amélie.

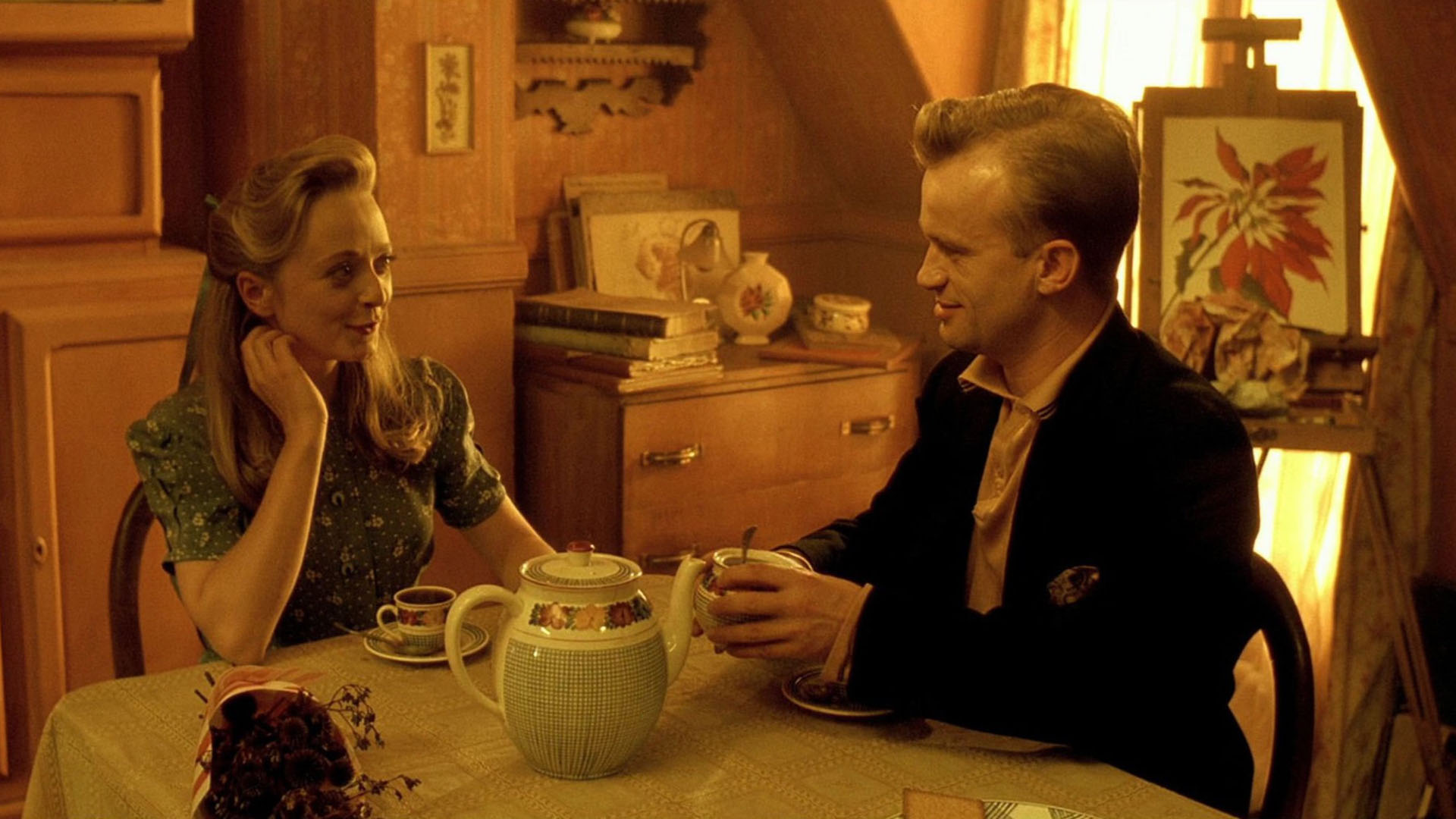

At heart though, they’re not so different. Under everything else, Delicatessen is essentially an offbeat romance between a woman who plays the cello and a man who plays the singing saw. Like Amélie, it’s a dissection of French life, with some quintessentially French characters (what other country lets the clown be the hero?). They’re even set in oddly similar Parisian apartment buildings. And they’re both very yellow.

Watching Amélie in the context of Jeunet’s first two films (let’s not talk about Alien: Resurrection) and pulling it apart from its 2000s cultural ubiquity and twee social influence, it really seems like quite a different film too. Sadder, stranger, a little bit more grubby.

So, maybe next time you’re stuck at your parents’ house and mum reaches for the Amélie DVD, maybe suggest Delicatessen instead. Look mum, it’s the same director, there’s a big knife called ‘The Australian’, it’s offbeat, life-affirming, very French, so French, and honestly there’s only really a very little bit of cannibalism.