Blonde was always going to be controversial – because it’s a work of grotesque sadism

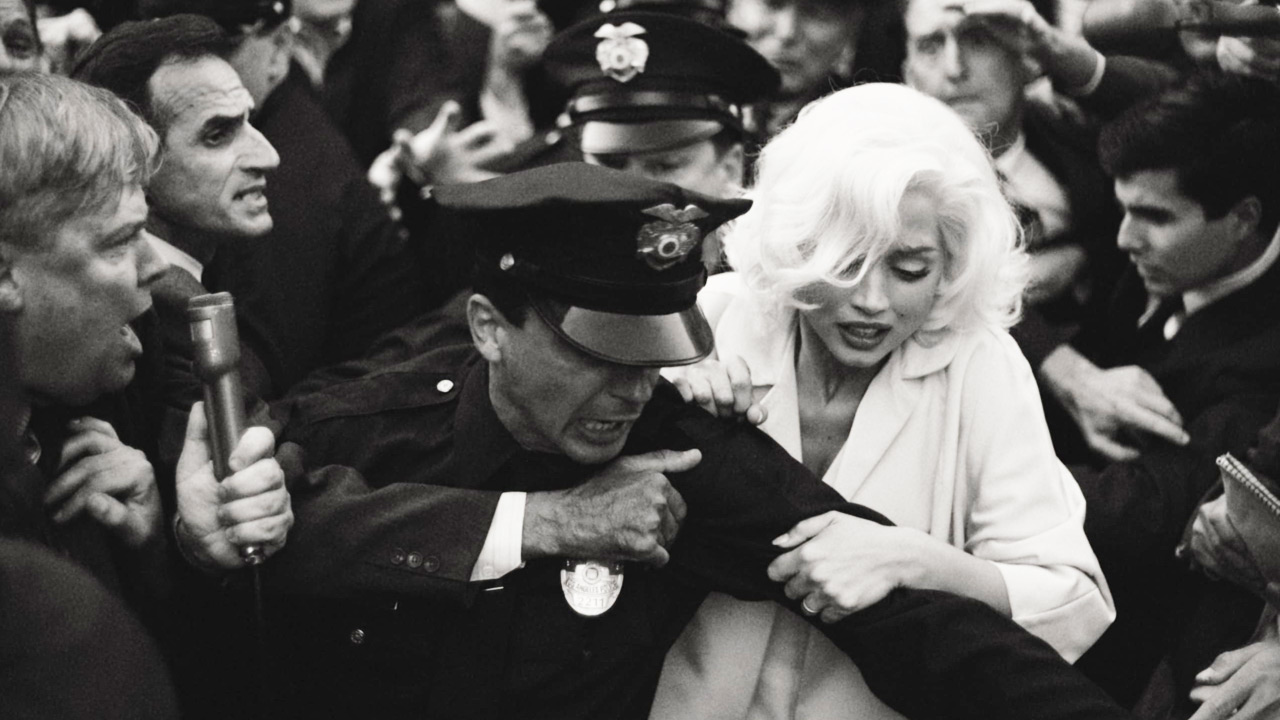

Director Andrew Dominik’s quasi-biopic about Marilyn Monroe has everybody talking—for all the wrong reasons. The Hollywood superstar has been resurrected so she can be exploited once more, writes Luke Buckmaster.

The star born as Norma Jeane Mortenson always longed to be a celebrity, and became the ultimate kind: so famous her life and legacy is in an endless state of reinvention. Mortenson became Marilyn Monroe, who became a blank canvas or Rorschach blot: an empty space onto which the latest artist and culture du jour can project, everybody seeing something different. For celebs like her, pop culture’s infinite cycle allows no final resting place: just another book, another spray of street art, another line of t-shirts, another set of fridge magnets, another input prompt for Dall-E.

And in the case of Andrew Dominik’s inevitably controversial new film Blonde: another gross feat of reincarnation, returning her body to life so it can be exploited anew. The director’s apparent intention to turn his adaptation of Joyce Carol Oates’ 2000 novel of the same name into a powerful feminist statement proves cold comfort, when it becomes clear he’s gone full Dancer in the Dark—reducing one of the most famous women of the twentieth century to nothing more than a victim. Of ghoulish men; of parental neglect; of vapid culture.

I haven’t read Blonde, but I have read two Monroe biographies: one by her most famous biographer, Norman Mailer, and the other by feminist Gloria Steinem. The former’s use of gooey, dripping prose (Monroe had a face that “came up on the screen like a sweet peach bursting before one’s eyes”, Mailer wrote, and “excited dreams of honey for the horn”) gave the impression of the author writing with one hand and doing something else with the other. Unsurprisingly, Steinem was more insightful, observing in her introduction that the much pored-over details of her subject’s life became “coloured pieces of glass in a kaleidoscope.”

Dominik’s approach is indeed kaleidoscopic, constructing Blonde as a series of fragments with an understanding—also shared by Mailer, Steinem and Oates—that you cannot paint a “genuine” picture of Marilyn Monroe, any more than you create a “genuine” depiction of Jesus Christ. The space is so loaded everything turns meta, and the surface is always subtext. So Dominik uses Monroe as putty for armchair psychiatry, his problematic commentary spanning the aforementioned victimhood to the insistence that many of her “problems” (here she’s a series of problems, not a person) boil down to daddy issues.

After recreating the legendary image of a subway air vent blowing up Monroe’s dress, the film jumps back to her childhood self (Lily Fisher), who is shown a photograph of a man (in reality Clarke Gable) whom her mother Gladys (Julianne Nicholson) says is her father, and a major player in Hollywood. And so it is inferred that Monroe’s entire career, entire legacy, comes down to wanting to find papa. When the 1933 Griffith Park fire hits, ash and ember raining down in Hollywood, Gladys drives towards the inferno rather than away from it, in a moment bulging with unsubtle metaphor.

Symbolic obviousness is one thing, but entering a turgid space ripe for co-opting by evangelical extremists is quite another. This is Blonde‘s bizarre anti-abortion thread, which includes a conversation between Monroe and her fetus, the fetus guilt-tripping her and begging not to be aborted, saying: “you won’t hurt me this time, will you? Not do what you did last time?” The film is its most visually, um, audacious during a shot presented from the point-of-view of Monroe’s vagina. For Dominik everything is up for grabs: her soul, her purpose, her resurrected and newly probed body.

Blonde arrives not long after another auteur-helmed film about an uber celebrity: Baz Luhrmann’s Elvis. This Baz Luhrmann production was directed by Baz Luhrmann, produced by Baz Luhrmann, co-written by Baz Luhrmann from a story by Baz Luhrmann, created with the bling and flair of Baz Luhrmann, bright and loud like Baz Luhrmann, with not even one scene fully devoted to a drawn-out stage or studio performance from Elvis. Because Baz Luhrmann is the DJ; Baz Luhrmann is the jukebox manufacturer; Baz Luhrmann is the visionary, reducing the king of rock ‘n’ roll to sound bites and a thrusting pelvis.

These films are interesting companion pieces because both make it baldly obvious the director is the star, and his subject pure iconography. Luhrmann’s offered one simple answer to who or what killed Elvis: it was his maniacal manager Colonel Tom Parker (outrageously played by Tom Hanks in the mode of a Bond villain by way of Foghorn Leghorn). Dominik also trades in simplistic messages, but on multiple fronts: it was bad men; it was daddy issues; it was…an aborted fetus?! Luhrmann doesn’t “do” politics, while Dominik, after directing three very fine narrative features (Chopper, The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and Killing Them Softly), just doesn’t know what he’s doing.

It might not be narratively interesting to say that Presley and Monroe died from addiction to very powerful and dangerous drugs, like many of their kind since then—from Michael Jackson to Prince, Whitney Houston and Heath Ledger. Unless of course that turns into a commentary about who or what caused their addiction, with all of us as suspects. It was the audience. It was the media. It was the producers. It was the broken ideals of a corrupt society. The origins of the term “star” imply an act of looking up and observing a force larger than ourselves. The lives (and deaths) of famous people must mean something, because if theirs don’t, neither do ours.

Marilyn Monroe may have been a victim of many things, but she was also talented, tenacious and determined. She even had the self-analysis to acknowledge her life wasn’t really hers, evinced in this melancholic line from her unfinished autobiography My Story: “I knew I belonged to the public and to the world, not because I was talented or even beautiful, but because I had never belonged to anything or anyone else.”

In light of that quote, I doubt Monroe would be surprised to see her dead body probed, her aborted fetus resurrected. The good news is: when your legacy is adrift for eternity, nobody gets the final word.