Briar March on anti-nuke activism doco Mothers of the Revolution

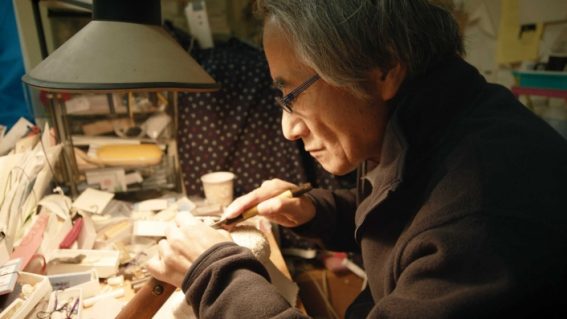

Director Briar March tells us about Mothers of the Revolution, a documentary on the anti-nuke activists of the Greenham Common women’s peace camp.

A very different existential threat faced the world in 1981, when a group of women started what would be an extremely long-running protest about nuclear weapons being based at RAF Greenham Common in Berkshire, England. Now, forty years later, Briar March’s documentary Mothers of the Revolution plays at Whānau Mārama: New Zealand International Film Festival, telling the story of these daring, everyday women, and their role in changing the world.

FLICKS: Describe your film in EXACTLY eight words.

BRIAR MARCH: How the Greenham Common women changed our future.

How did you first take an interest in the Greenham Common protest, and when did you know you had to make a film about it?

The first time I discovered the Greenham Common women’s peace camp was when I was editing the film No Nukes is Good Nukes (2007), a documentary about the history of anti-nuclear activism in Aotearoa, directed by Claudia Pond Eyley.

Claudia shared with me her memories of visiting the camp, and described the hardship the women had to endure, living outside a military base in icy cold winters under just a tarpaulin, year after year.

But in the decade that followed I rarely heard or read of the social movement and it took a moment for me to remember what it was when producers Leela Menon and Matthew Metcalfe approach me to direct a film on the subject. But this is also what piqued my interest and made me want to do it. Why had this incredibly significant and critical social movement slipped from my radar?

It was coming up to the 40 year anniversary of the formation of the peace camp, and it felt like there was enough distance to look back and evaluate the work these women did, exploring not only what have they had achieved, but what can we still learn from their activism.

Has there been a protest movement to match the anti-nuke movement since?

It’s difficult to compare social movements with each other, they are all so unique and specific to their unique sociopolitical environments, but I don’t think there would be many movements that have united as many communities and nations over such a long period of time as the peace movement has.

Most people who grew up in the 80s will recall and relate to the fear and anxiety around nuclear weapons. For us in Aotearoa, the nuclear submarines in our harbour, and the nuclear testing in the Pacific are significant markers of that time.

The potential of nuclear war was a very real threat. There were end of the world parties. Some women told me that they actually considered how they would kill their children; living a life after a nuclear explosion was so devastating it was beyond comprehension. Views on nuclear warfare, defence, and disarmament, seemed to divide people on both political and emotional fronts.

The only issue that comes close to that for me is climate change and while the need to abolish nuclear weapons has not gone away, the sense of despair, helplessness, and anger felt about the issue of climate change reminds me of how nuclear proliferation was for people back then.

Politicians and intellectuals were endlessly pontificating on nuclear disarmament but it was the voices of ordinary women that transported these discourses into honest and powerful calls to action, and helped the world to really wake up. Isn’t it interesting how some of the strongest climate action work to date has also come from young women in a similar fashion?

But unlike the threat of nuclear weapons, I think climate change is a more difficult concept to grasp tangibly in our minds. Our planet isn’t at risk of being destroyed by the click of a button, it is a destruction that is happening slowly in the background. And I think this is part of the challenge we need to address when it comes to getting people to respond to this issue.

I see the story of Greenham Common as a clear example of how we can make change in the face of existential crisis and how it can work, and that is why I think this film is so important for people to watch right now.

What were some of the ways the contribution and commitment of these women were minimised by media or the status quo?

Some media, although not all, had a slanted angle in the way they portrayed the women, showing them as overly emotional, irrational, and naive in their political views. Lord Heseltine, who was formally Margaret Thatcher’s Minister for Defence, referred to the women as “wooly minded” (this was a witty reference to their hats). His view, which reflected the view of the conservative government, was that the UK needed the missiles for defence, the Greenham women stood in the way of this message.

There was a special unit set up by Heseltine to disseminate misinformation about the women, it was called DS19, and in the film we show various examples of how it manifested in the press, featuring articles and newsreels about the peace camp being infiltrated with Russian spies, the women being man haters, burly lesbians, and abandoning their children.

Some of the descriptions of the peace campers were so extreme and outlandish, that the women couldn’t help but laugh at it, using these negative portrayals as creative material for their songs, actions, and hand made zines.Thank goodness they had such a great sense of humour!

Do you have thoughts on how we can apply the lessons of this protest movement to present – or future – issues?

It’s easy to feel pessimistic about the situation we are in right now. What does real change look like when we are not at the negotiating table with political leaders making the rules and regulations on climate change and nuclear weapons?

I am sure the women at Greenham Common could have felt similar when thinking about the cold war, but their story shows us that everyone can have influence. Their story also demonstrates the importance of hope, a hope that is not naively idealistic, but one that is cemented in the belief in humanity and that celebrates the power of community and shared vision.

It can be very magical when people come together and do something collectively. It can have a profound impact on us personally and reshape our entire way of seeing the world, that is what we see in this story.

The Greenham Women also called out sexism and violence against women and children, and they discussed issues around racism, inequality and police violence. What is happening now with the Me Too Movement and Black Lives Matter appear to be a continuation and development of those struggles.

During production, what was the biggest hurdle you had to overcome?

Each film has a unique mountain to climb, and this one was particularly challenging for so many different reasons. We also had Covid to contend with, which made the archive and editing process more labour intensive.

The story has so many different elements and layers, which is why it is so compelling, but also why it was more challenging than other films I’ve worked on to write.

There were endless ways to convey the history, and so many personal stories to choose from. Knowing which parts we would leave in and which parts were for another film was a big responsibility. I felt a duty to everyone involved in the peace camp, but at the same time to our audiences, and I knew that in the confines of a 100 minute film I couldn’t do it all. I also really wanted to reach a younger audience, not just the generation who lived through through the cold war, and so I had to think about what context and information they would need to understand the story.

Thank goodness for the amazing team of creatives that I got the opportunity to work with, especially my editors Margot Francis, Simon Coldrick, Tim Woodhouse, and John Gilbert (you can see I was pretty spoilt in that department!) Our researcher Phoebe Shum also made a significant contribution to finding the archive, and the film wouldn’t be the same without the work she put in.

Each woman I interviewed was exceptional, and some of these people didn’t end up in our final edit. This was not anything to do with their personal stories or their performances, it is merely the fact that there are still probably about other 10 films that could still be made on this subject.

For you, what was the most memorable part of this whole experience?

Well, that question is really easy to answer. Meeting the women who feature in this story was more than just a privilege, it was an honour to behold.

Having had the unique opportunity to sit with them for several days at a time and hear their stories, not just hear, but really, really listen. Listen and attempt to imagine.. What would it have been like to live through that experience?

For many of the women, it has been such a defining chapter in their lives, and it has continued to shape how they are as people since. Pretty much every women I met and interviewed is still engaged in activism to varying degrees. And the spirit and magic of the peace camp lives on not just in their lives but in their children’s lives, and in their communities. Rebecca Johnson puts it so well in the film when she says:

“The other major impact is in the hearts and minds of every single women who ever got involved and all the partners and children, which includes a whole lot of men and a whole lot of boys growing up who were connected to every single women who ever went to Greenham, whether she went for a day, or she lived there for several years. Greenham had an impact in how we live our lives.”

Having had so much time to soak up the women’s stories and to relive them through the medium of cinema, the Greenham women story as also widened my own perspective and my feelings on activism and protest. Now I can see so many more ways I can be an activist through my films and still make work that is cinematic and moving. At the end of the day, making movies is hard work, and so they may as well say something important, and make a real difference. That is why I hope you all see this movie!