Cannes: the Palme d’Or winner, the boo-ed runners-up, and a talking fridge

Sarah Watt concludes her Cannes Film Festival coverage on a very high note—perhaps the highest with a screening of this year’s Palme d’Or-winning film. She also reports on the awards ceremony (from a very bemused crowd of press), some unawarded gems, and a Q&A with a talking fridge.

For more coverage on this year’s Cannes:

Opening Night film The Dead Don’t Die

Early looks at great films

Rocketman and Werner Herzog’s latest

Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood

By Thursday in the second week, with two days to go until the Closing Film, Cannes had noticeably thinned out. Many people left after Once Upon A Time in Hollywood, although if they went without a goodbye kiss from Bong Joon Ho’s incredible Parasite, then they didn’t get the best of the Festival.

This is the Korean master’s follow-up to the recent Snowpiercer (almost universally praised) and then Okja (less raved about, but still an interesting piece of work from a director whose oeuvre defies genre categorisation, other than to say “he’s a visionary” and “things will probably get nasty”).

Parasite invokes both those cries, with the most exquisite camerawork I’ve seen all Festival (even better than Malick’s), incredible performances from Bong regulars as well as newbies, and a killer storyline. The less known beforehand, the better, but it’s billed as a “family tragicomedy” and succeeds on both counts. It also has a strong social message, and in the director’s own words, it’s “A comedy without clowns, a tragedy without villains”.

And then, on Saturday night, it went and won the festival’s top prize, the Palme d’Or.

In the theatre reserved for press to watch the Closing Ceremony telecast live, the crowd erupted for Director Bong. It is truly well-deserved. But the award came at the end of a prizegiving that elicited more bemusement and boos (that’s right, the journalists get a little loose when we’re all in a separate room from the glitzy-dressed stars) than elation—so one can feel good for the humble, open and engaging Korean director, but perhaps less pleased for some of the other winners whose success was met with incredulity.

One such award went to the new social drama from the Dardenne brothers, Young Ahmed—a controversial tale of religious fundamentalism and tolerance, which is both timely and worrying. Some found the story a little on-the-nose (some may find it outright objectionable), but it’s also sensitively shot, naturalistically acted and indisputably illuminating, if helping people to understand each other’s motivations is important to you. The elderly Belgian filmmakers shared the Best Director prize.

Young Ahmed

The crowd was similarly derisive of Emily Beecham’s Best Actress win for Little Joe. I actually thought she was fine, and to be honest I hadn’t been particularly struck by any other female performance in the Competition films.

But when the first Black Woman Director, Mati Diop, won 2nd prize for her film Atlantique, even the faces in the Grand Theatre Lumiére conveyed displeasure. It’s a hard world, filmmaking (and Atlantique is a very solid film—snapped up by Netflix overnight, although to be honest it probably works better in a cinema setting) and of course, get a bunch of critics in one room and they’re bound to be particularly vociferous.

It was pleasing, however, to see Week One‘s highlights Les Misérables and Bacurau share third place. If we’re lucky enough to get those in the New Zealand International Film Festival, they come highly recommended.

Everyone seemed happy with Antonio Banderas winning Best Actor for his 8th collaboration with Pedro Almodovar in Pain and Glory. The actor noted it had taken him 40 years to get an award, and by all accounts, he is outstanding in the film.

This year women were better represented in the 21 films In Competition, and three of their films won prizes—the last being Céline Sciamma’s (Tomboy, Girlhood) 18th-century romantic drama Portrait of a Lady on Fire, which got Best Screenplay.

Portrait of a Lady on Fire

It’s a truly beautiful film, excitingly peopled almost exclusively by women (though bookended by scenes of male extras) and its leads are magnetic. Interestingly, male critics I spoke to responded more deeply to the love story than I did, but it’s still a fine and engaging piece of work.

Another timely female-focused drama (not in Competition) was Share, the first feature from female director Pippa Bianco—a troubling, important and extremely accomplished portrait of a teenage girl whose life is torn apart when a cell phone video surfaces of her at a drunken party. It’s a hard watch, may be triggering for some, but treats its characters and viewers with restraint and realism.

On the more “fun” side of film-going lies the brilliantly witty, imaginative and surprisingly touching French comedy La Belle Epoque. Desiring to relive a seminal moment of happiness from his 1970s youth, Daniel Auteuil’s retired cartoonist enters an immersive world of nostalgia and revelation, with unexpected results. The filmmaking is top-notch, with effortless performances (Auteuil and Guillaume Canet the best in years) and an enormous sense of spirit. It would have made a much better Opening Film than The Dead Don’t Die.

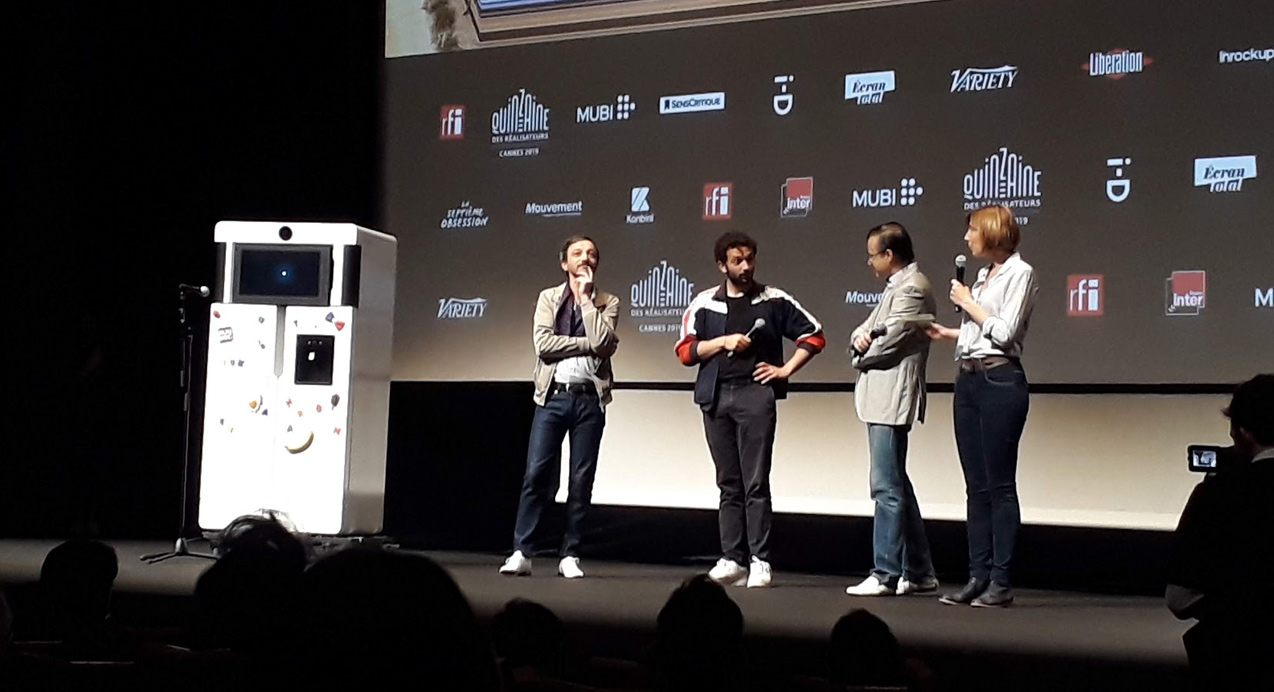

Similarly entertaining and even more bizarre in its conceit is Yves—the story of a loser, a wannabe rapper whose life is turned around with the help of an artificially intelligent fridge (the titular Yves). Sounds crazy, no? Yes—and ecstatically crowd-pleasing, with laughs-out-loud galore.

At the Q&A after the screening, Yves even joined the actors on stage and answered his own questions.

Q&A with the cast and whiteware of Yves

Unawarded but impeccable in all aspects of its production was Terrence Malick’s A Hidden Life—a somewhat gruelling but utterly compelling three hours about a young Austrian farmer conscripted into the Nazi army during WWII, whose conscience will not allow him to swear an oath to Hitler. It can be added to the long list of “issues movies” at Cannes.

(This is not a critical term, because if film isn’t used for higher purposes than pure entertainment when the world’s in the state it is, then there’s something very wrong. Actually, I’m not alone in this view, with the president of this year’s Cannes jury, Alejandro González Iñárritu, saying “Cinema must try to raise the global social conscience”. Hear, hear.)

In that same vein, Ken Loach tackles injustice and exploitation of those in desperation, in his typically brilliant yet low-key film Sorry We Missed You. Despite the performances sometimes veering towards “acty”, and a litany of familial and economic blows which batter our protagonists, it’s a heartfelt and extremely moving piece, horribly relevant and resonant.

Italian film The Traitor also tackles big, real-life issues with its overlong and over-talky true story of a Mafia informer who had hundreds of former colleagues put away in the 1990s. It doesn’t touch Goodfellas heights in its execution, but it speaks of truth and courage, and the performances and period design are reminiscent of Olivier Assayas’ long, detailed Carlos.

And that about sums up the films that I saw this past fortnight. It was, as you can tell, a mighty Cannes. Now Quentin is back in the edit suite, adding 30 minutes to his overlong film, and I’ve travelled on to Italy for a break. All New Zealand audiences have to do is hope we see the best of these offerings in our own, closer-to-home festival from July. Bonne projection!