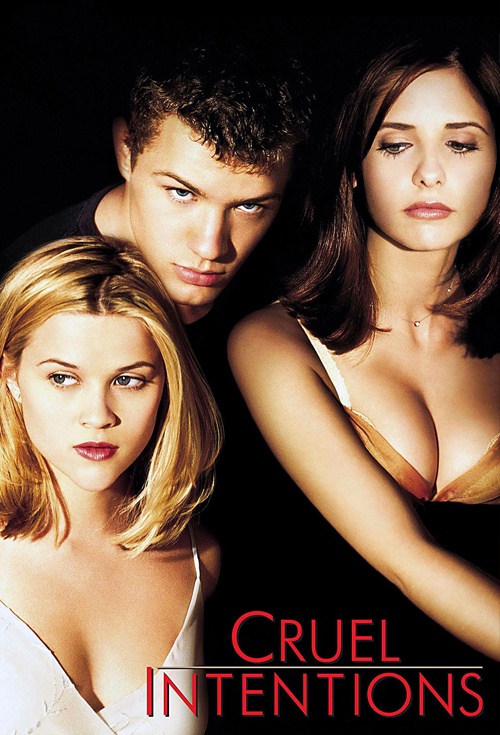

Cruel Intentions is 20 years old, still darkly perverse and delightfully depraved

With Cruel Intentions turning 20, Katie Parker looks back at the darkly perverse and delightfully depraved teen movie phenomenon.

If one were to try and get a coherent picture of adolescence in the 90s only by watching the spate of teen films released by Hollywood in 1999, it would be a rather confounding project.

Was it the raunchy sex farce seen in American Pie? A darkly comic and politically fraught battle of wits as per Election? A smart and sassy riot grrl romance like 10 Things I Hate About You?

Or was it a lush, lascivious and deeply depraved simulacrum of the 18th-century French court, populated by trust-funded prepsters trading in Gatsby-ish aesthetics and storing cocaine in iconic crucifix vials?

Of the many, many teen films released 20 years ago, it is Cruel Intentions that stands out as the moment Hollywood’s teen-movie boom really hit fever pitch—and the most beautiful, bizarre and strangely enduring thing to be born of it.

Directed by Roger Kumble and loosely adapted from the 1782 French novel Les Liaisons Dangereuses, Cruel Intentions follows wealthy New York teens Katherine (Sarah Michelle Geller) and Sebastian (Ryan Phillipe) as they spend their summer playing devious sexual games with their unwitting peers.

Fuelled by their icky yet unconsummated lust for one another, this involves Katherine taking revenge against an ex-boyfriend by manipulating his naive new girlfriend Cecile (Selma Blair), and Sebastian setting out to bang proud virgin, “paradigm of chastity and virtue” and daughter of their school’s headmaster, Annette (Reese Witherspoon)—clearly all good-natured fun and games.

The stakes are raised, however, when Katherine and Sebastian make a twisted wager (rich people love twisted wagers) as to who will succeed in their ghoulish antics—the prizes being Sebastian’s vintage Jaguar or sex (and not just regular sex!) with Katherine, respectively.

Soon enough, people are being blackmailed, teens are being deflowered, gay slurs are being bandied about and hundreds of teens are shaking their heads in slow motion to Bittersweet Symphony.

Campy, raunchy and just a little bit porny, it was darkly perverse and delightfully depraved—and everything one is looking for during the heady, confused, impressionable time that is adolescence.

Seared into my 13-year-old mind: Cecile and Katherine’s creepy girl-on-girl kissing lessons; Tara Reid screaming “There are pictures of me on the internet!!!”; and of course, Buffy the Vampire Slayer gesturing buttwards saying “you can put it anywhere”.

Before Gossip Girl, Katherine and Sebastian were the original upper East Side enfants terribles, slinking around penthouses, nursing Catholic-themed coke habits and ruining lives—their parents shown only (in perhaps best piece of mise-en-scène ever) framed in a photo posing with Bill Clinton.

Given all this titillating debauchery, of course, the film was a commercial and cultural hit, launching and defining the careers of its young cast, coining many an iconic one-liner (“email is for geeks and paedophiles”) and gaining a reputation for being both utterly messed-up and extremely entertaining.

Critics, though, were not so sure. Upon its release, The New York Times called it “exploitative”. The Washington Post deemed its “profound misanthropy” both “depressing and impressive”. Roger Ebert lamented—in an otherwise largely positive review—that “teenagers once went to the movies to see adults making love. Now adults go to the movies to see teenagers making love”.

For a generation raised on John Hughes froth it’s not surprising that, for these adults, Cruel Intentions forewarned a liberally lubed-up slippery slope to moral depravity for horny, guileless teenagers. And now we know they never needed to worry at all.

From the ‘nice jock’ fantasy of To All The Boys I’ve Loved Before, to the sensible sex-positivity of Blockers, to the grimly neutered Five Feet Apart (in which Riverdale’s Jughead literally cannot come within a normal distance of the girl he’s dating), today’s Hollywood teen output has been drastically slimmed down and sanitised. Genuine desire—and all the hellish perversity that goes with it—has been all but erased from the cinematic teen experience.

As such, Cruel Intentions remains more-or-less equally as shocking as it was 20 years ago—and 10 times more ‘problematic’.

To watch Cruel Intentions today, several things stand out as having not aged particularly well: The laissez-faire attitude to consent; the comical rendering of revenge porn; and of course, the unfortunate use of the f-slur tainting Joshua Jackson’s otherwise darkly brilliant turn as Katherine and Sebastian’s flamboyant co-conspirator.

Yet as definitively of-its-time as Cruel Intentions was, two decades on there remains something strangely modern, prescient even, about its transgressions.

Set in a world of dark red, lush velvet interiors cast against the cold, desaturated blue of the outside world and put to a soundtrack of angsty, aching music from the likes of Placebo, Blur and The Verve, perhaps what is most scandalous—and most timeless—in Cruel Intentions is not the rampant teen promiscuity but the sense of nihilism that pervades and propels the film.

It is, after all, not kinky fun that drives the sordid sex games and social sabotage that Katherine and Sebastian carry out but seething, barely repressed contempt: boredom and frustration with artificial niceties of their social lives (“I’m the Marcia fucking Brady of the Upper East Side, and sometimes I want to kill myself”), the teens here are not looking ahead to the brighter horizons of adulthood—which, as that Bill Clinton photo suggests, is not much better.

Instead Katherine and Sebastian live as though they are on the brink of the apocalypse: waging a petty interpersonal war of genuine contempt against their peers, their malevolence is executed not with joy but with grim satisfaction—the desire to destroy a defence against, and manifestation of, an existential dread that is perhaps now too confronting too depict.

As a new generation comes of age on a dying planet consumed with the increasingly futile task of accumulating capital, it is no wonder that studios have made the choice to ply young people with peppy, aggressively positive depictions of teen life—with the world feeling like it might really be ending, even the once ubiquitous dystopian teen drama is perhaps no longer so profitable.

Yet the fact that Cruel Intentions could never be made today isn’t evidence that it has not aged well. Instead, it has only grown more potent—a portrait of callous cunning in which, even when the good guys prevail, the villains remain the heroes 20 years later.