Dune: Prophecy defies prequelitis, adding more spice and sorcery to the sci-fi saga

10,000 years before Denis Villeneuve’s films, the origins of the Bene Gesserit are explored in new series Dune: Prophecy – premieres on NEON November 18. Dodging the pitfalls of most prequels, it’s a seamless extension of the Dune universe, says Steve Newall.

(Contains spoilers for the Dune feature films)

Sequels, prequels, requels—Hollywood can’t get enough of reminding us about things we used to like. We’ve been hit in recent years by a wave of nostalgia IP mining past decades (not all of it bad, it must be said). But too many of these new projects seem to miss the point of what the originals are about, combined with a fervour to reduce the potential of boundless creative universes to simplistic storylines, all too often revealing [new character] is [old character]’s [child/parent].

Stuff all that child’s play, says Dune: Prophecy—think a bit bigger, already.

Premiering in the same year as part two of Denis Villeneuve’s superb adaptation of Frank Herbert’s saga-igniting novel, there’s been no time for nostalgia to form (well, of Villeneuve’s Dune, anyway). Even more enticingly, the new series doesn’t just focus on a previous generation, or try to cast a young Oscar Isaac lookalike—Dune: Prophecy is set a whopping ten thousand years before the events of the two films. 400-odd generations. Take that, Gladiator II, Scream, however many Star Wars you choose to mention, etc.

The sisterhood of the Bene Gesserit—reverend mothers to some, space witches to others—has a vital role to play in the Dune feature films. The pics reveal ten thousand years of bloodline manipulation to produce the Kwisatz Haderach aka Timothée Chalamet’s Paul Atreides. His genetics, training and experiences on Arrakis create a powerful entity who can see into both the past and future, and who ends Dune: Part Two by (cynically?) exporting jihad to the rest of the known universe

But waaay before that, as Dune: Prophecy chronicles, human society had to reestablish itself after overthrowing thinking machines and conscious robots. The structure of (and infighting between) semi-feudal society, based around the Great Houses (Atreides, Harkonnen etc) is perhaps more reminiscent of Game of Thrones in this show than in the films—though Ned Stark and co. never had to come up with decrees like “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind” after any of their wars…

How recently this overthrow of artificial intelligence is, and the related distrust in it ever gaining the upper hand, has a huge role to play as Dune: Prophecy unfolds. As well as providing context to the intriguing mix of high and low tech in the films, this strict rule against AI explains why humanity has needed to pursue other forms of computational power in biological fashion—seen in the Dune films as mentats (human computers) or the space guild (space-folding interstellar navigators).

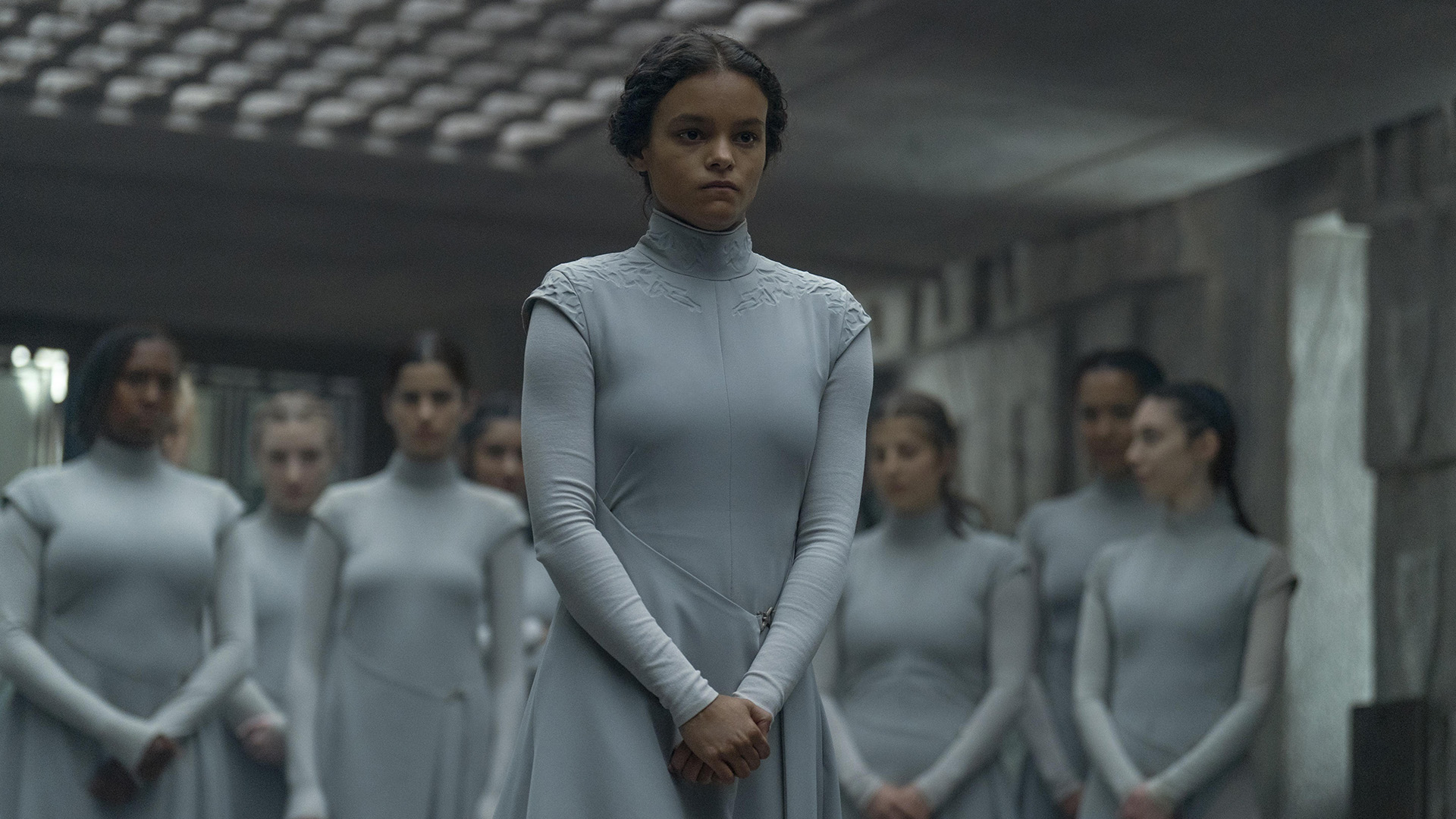

Then, of course, there’s the Bene Gesserit—depicted in Dune: Prophecy soon after its formation as the Sisterhood. As the series begins, Valya Harkonnen is at the helm—her sister Tula a Reverend Mother supporting her. Just as Villeneuve’s films benefitted from superb casts, Valya and Tula are brought to life by actors with incredible screen presence. Emily Watson (Breaking the Waves, Punch-Drunk Love, Chernobyl) is chilling and determined as Valya, while Olivia Williams (Rushmore, Dollhouse, The Crown) conveys pain and vulnerability as her sister.

In the “present” of Dune: Prophecy, the Sisterhood is primarily concerned with consolidating power by appointing Truthsayers to each of the Great Houses. Trained to detect falsehood, they secretly work in cooperation with one another, to guide the Houses in the direction the organisation desires—and to control and propagate the bloodline that will be their work for millenia.

We see the early days of sisterhood “sorcery” here, in a fascinating expansion to the universe of the films. The origins of the commanding “Voice” are explored, as is the technique of Spice Agony, used by the Sisterhood to connect to the generational knowledge of their ancestors. If you wanted to know what Rebecca Ferguson’s character experienced in Dune: Part Two, it’s shown in terrifying fashion here—a mausoleum filled with scary apparitions of the past… some of whom still hunger for vengeance.

Alongside Watson and Williams, Jessica Barden and Emma Canning play younger versions of the same characters, depicted in flashback, carrying out morally questionable deeds as they struggle to right historic wrongs to the Harkonnen family. Each is a great double for the older versions of their character—but none of these four escape without moral stains of their own, their actions foreshadowing Harkonnen and Bene Gesserit misdeeds to come.

In fact, if the first episodes of Dune: Prophecy are anything to go by, the Sisterhood seems to be built on some rotten foundations—and the Voice, as it’s used here, is both chilling and stemming from a place of personal trauma and despair.

Those deep-voiced commands are far from the only sorcery rearing its head here. Desmond Hart cuts an enigmatic figure who’s survived many tours of duty on Arrakis—including, apparently, being swallowed by Shai-Hulud, the great sandworm of the desert. Hart lost an eye to the encounter, but he’s come back with so much more—including a religious devotion and some unexplained abilities of his own. As Hart, Travis Fimmel initially comes off as a Jason Momoa-alike, but is soon channeling a lot of his character Marcus from sadly-cancelled sci-fi series Raised By Wolves, who had similar experiences with resurrection and supernatural powers.

Vanya and Desmond are destined to clash, both directly and in their manipulation of others—most notably Mark Strong’s Emperor Javicco Corrino, ruler of the Imperium (but always needing to assert authority over the Great Houses). In this regard, things do get a bit Game of Thrones-y in terms of plot and also the look of the shadowy palaces in which much of the scheming and intrigue take place.

But while Dune: Prophecy’s first eps don’t show a lot of Arrakis outside of Hart’s short flashbacks and assorted other visions plaguing the Sisterhood, the show feels like a seamless visual extension of the screen universe created by Villeneuve. It’s an unforgiving place, breeding unforgiving people—seeing the Harkonnens chopping up furry whales amid a grimly freezing landscape shows the brutality that will continue to be at their core, for instance.

On the other hand, there are also cool space limos, appealing space drugs, and the odd space sex club—so things aren’t all bad. Hey, it might not be true for all the show’s characters, or the future victims of Paul Atreides’ jihad, but for viewers of Dune: Prophecy, I foresee the best is yet to come…