Everything Now’s premise is some classic John Hughes fare

We’re all drowning in content—so it’s time to highlight the best. In her column, published every Friday, critic Clarisse Loughrey recommends a new show to watch. This week: Getting young and reckless, crossing off a teen’s bucket list in Everything Now.

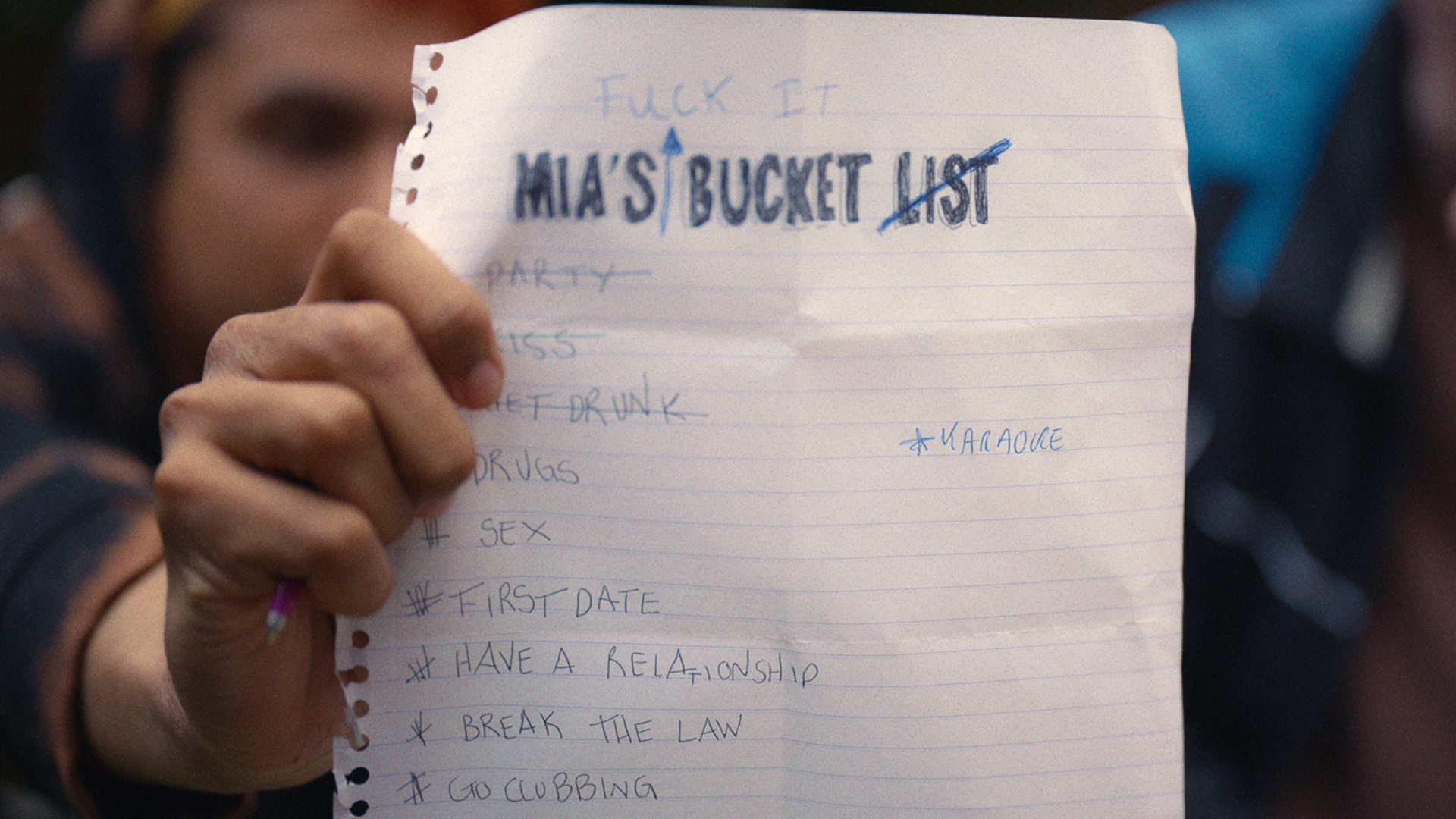

The premise of Netflix’s latest teen series, Everything Now, is some classic John Hughes fare: Mia (Sophie Wilde), who’s about to turn 17, realises that she’s fallen drastically behind her peers when it comes to the traditional rites of teendom. She hasn’t had sex, she hasn’t done drugs, she hasn’t gotten drunk, or done a petty crime. So, she writes out her list, gathers her squad (played by Noah Thomas, Lauryn Ajufo, and Harry Cadby), and starts on the weighty work of being young and reckless.

Mia’s your perfect, totally clueless teen protagonist. She signs up for a theatre class to impress a pretty girl (Jessie Mae Alonzo’s Carli), even though she can barely stammer out a single sentence. She goes to the mall to get a high-femme makeover from the popular girl (Niamh McCormack’s Alison) flashing daddy’s credit card. She gets the sex talk from her desperate-to-be-cool mother (Vivienne Acheampong), who starts pulling rampant rabbits and condoms out of a secret stash she’s clearly kept saved for this very moment.

But, Ripley Parker’s eight-episode series, in truth, has something a little different on its mind. Everything Now is a show about how the experiences the movies told us we share, barely start to reflect the reality of the ones we do: the way we look at our bodies in the mirror, our feelings about sex, the way a relationship with a parent can shift suddenly and without notice.

Mia hasn’t had sex, done drugs, or gotten drunk at a party because, for the last seven months, she’s been in treatment for anorexia. And, instead of being able to protect that baby bird vulnerability of reentering society, she’s had to run headfirst towards some vaguely defined “old normal”—otherwise she’ll have to spend the rest of her school days being known only as “the anorexic girl” everyone calls “brave” because they’re incapable of seeing the human being behind the illness.

It’s tricky, to root something so real and painful within a genre known for its frothiness. Still, Parker has found a miracle worker to carry out her vision: Wilde, an Australian actor whose breakout arrived earlier this year with A24’s horror Talk to Me. She played another Mia there, one haunted by literal ghosts, but not so dissimilar in character. Both are young women in moments of crisis, who are untethered and riddled with self-doubt, who lash out and mistreat those closest to them, and yet are so much kinder and stronger than they believe themselves to be. Wilde lets every contradiction swim around in those big, brown eyes of hers.

Everything Now is so much better an exploration of anorexia than we’re used to precisely because it isn’t fixated on turning Mia into a saint or treating her psyche like a maths equation. In fact, her mother, in a session with Mia’s doctor (Stephen Fry), rails against the toxicity of social media, convinced its impossible beauty standards are responsible for her daughter’s illness.

Mia rolls her eyes. That’s not even the start of it—she’s reached this point because her mother is so overbearing in her life that she feels like she’s “freezing in her shadow” and because she’s seen her scrape uneaten meals in the bin. She’s like this because she’s terrified of sex, because she feels she’s “incorrectly feminine,” because it’s overwhelming to be a body constantly perceived by the world. Everything Now doesn’t ascribe motivations, because there’s no “catch-all” solution to what happens when your own reflection makes you feel sickly.

And neither is the journey out of this hellhole something you can track in a three-act structure. It’s really no spoiler at all to mention that we, at one point, see her relapse. Thankfully, the way we talk about eating disorders has matured enough that it’s almost universally acknowledged that recovery isn’t a straight line. But Everything Now, in particular, also doesn’t feel the need to assign a specific trigger moment. It doesn’t happen because a piece of clothing feels too tight, because someone said the wrong thing, or thrust a giant piece of cake in her face (although all these things happen). Mia relapses because she’s trapped in the centre of an emotional maelstrom.

It’s chaotic and, at times, her family and friends get caught up in the destructive path. Certainly, she’s not to blame for her own illness, but the series is often at its most moving when it acknowledges that seeing someone you love fall sick in this way can take an enormous toll. Mia’s brother is emotionally neglected by his parents; a close friend feels like the sacrifices they made to help her haven’t been acknowledged.

All those John Hughes movies were meant to be a comfort, because they presented an affirming hierarchy of identity for a group of people desperate to figure out exactly who they were. A teenager could define themselves as the nerd or the party animal, the victim or the bully, the slut or the virgin. But Everything Now embraces the genre, only to offer a more substantive alternative—that the teenage dream doesn’t have to make sense, and it definitely doesn’t have to be easy.