Gaylene Preston and her battle to get Kiwi classic Mr Wrong into cinemas

In an exclusive extract from her memoir published this week, Dame Gaylene Preston details the rejections, ovations, and manoeuvring involved in Kiwi classic Mr Wrong’s difficult journey to cinema screens.

Today, Dame Gaylene Preston’s Mr Wrong is rightfully considered a Kiwi classic, and positively regarded further afield by the likes of Fangoria as a “self-identifying feminist horror film,” but in 1985 the filmmaker struggled to get her groundbreaking pic into New Zealand cinemas.

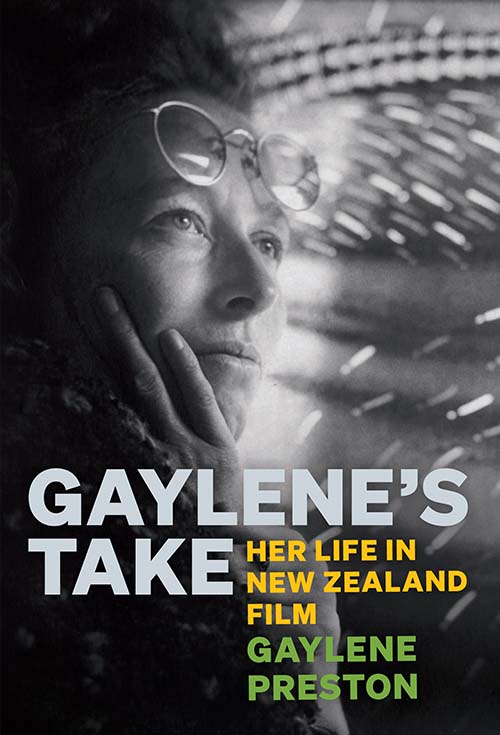

It’s just one of the moments recounted in Preston’s excellent newly-published memoir Gaylene’s Take: Her Life in New Zealand Film (having read an advance copy, I can’t recommend strongly enough that you order a copy here). Also recommended: checking out NZ On Screen’s extensive new Gaylene Preston Collection.

In the exclusive extract from Gaylene’s Take that follows, written in the engaging style that brings Preston’s memoir to life, we hear about the battle waged—and eventually won—to bring Mr Wrong to cinema screens where it would thrill (and chill) audiences:

Truth is, local films come onto the local circuit without the benefit of millions of offshore dollars already spent on publicity. They don’t have Tom Cruise in them. They have John Bates or Donna Reece doing the heavy lifting. Releasing a local film is hard work – particularly when the audience in those days was unforgiving of any local film that didn’t click. We care more about our own culture. We get sadder when something doesn’t work. But if you don’t have the promotional money – the press and ads budget – to run a good campaign, you have to have a lot of resourceful, energetic friends. That’s how Goodbye Pork Pie thundered up and down the country and Smash Palace caught the local imagination, making Bruno Lawrence a local star. But Mr Wrong didn’t have a part for Bruno, and Sam Neill had ridden the silver rocket to Australia and beyond, where he continued a beautiful career. There were no lead roles for Kiwi women that could have made them stars, which meant we had no women’s marquee names.

By 1985 Kerridge and Amalgamated were in the habit of putting local films, no matter how promising, into their cinemas a couple of weeks before the school holidays. This meant that whatever business the film did, when the Disney film arrived off the screen it went. Cinemas tended to still be single screens, so that would be that. Distributors always prove what they know already. If it’s ‘a dog’ but it’s doing good business, it’s still outta there for Disney. All that heartache and pain buried, come the school holidays. ‘Next.’

But, knowing all this – love the one you’re with. We started with Kerridge. We screened a print to them in Auckland in their screening room. Dead silence. They sat like stones. Not even a slight titter. Sad sighs when the lights came up as they scurried back to their offices to leap on their phones and tell everyone how bad it was. Slightly better reaction from Amalgamated. Joe Moodabe said there were some good shots there. ‘But . . . no.’

By this screening I have a pretty good idea what the outcome would be, and have already shown the film to Bill Gosden, the director of the Wellington Film Festival. In those days, the fledgling film industry experts considered it ‘non-commercial’ to screen your film in the Film Festival. According to the five people who thought they knew, only the pointy-headed who liked reading subtitles went (entirely untrue), and your film would be tainted by those challenging words – ‘art film’ – forevermore.

That festival had been my saviour when I first came back to Wellington from Brixton and was suffering life-threatening culture shock. I was delighted to find that I could go and see a heap of films I would have had to stand in a queue for hours just to get an advance ticket for in London. All I had to do was turn up and buy a ticket at the box office before the show and snuggle in – well, in those badly heated old theatres, I learnt to take a rug and a scarf and woolly hat before basking in the pleasure of the light on the screen.

The Film Festival brought good films from everywhere, documentary and drama, and screened them the length and breadth of the country. At a time when freighting heavy prints in metal tins was expensive and challenging (watch Cinema Paradiso if you haven’t already to see what I mean), this chain of festivals leap-frogged a programme to all the main centres.

Filming Mr Wrong on Roxburgh Street (photo by Thom Burstyn)

Pacific Films virtually closed down their operation for the fortnight of the Wellington Film Festival, and we all just went to the pictures. Bliss. I saw films by Frederick Wiseman and Agnès Varda and, wonder of wonders, actual Australian films. Until very recently it was hard to see an Australian film in a cinema in New Zealand. Unless they had a Hollywood deal, we didn’t see them. It works the other way round as well. They didn’t see ours. Thanks to the festivals, hope for cultural understanding was fostered. I love Australian films, so when it was announced that The FJ Holden was screening and the director was going to be present, I was in boots and all.

Michael Thornhill wasn’t entirely sober when he introduced his film. Swaying slightly, a tinny in his hand, he glared at the audience and spoke slowly, as if to a bunch of ten-year-olds.

‘All those who are media here, put your hands up.’

A couple of brave souls raised their hands.

‘Yeah? – well – here’s all I’ve got to say – if you like it – great – and if you don’t – shuddup!’

Refreshing. Muscular and flawed. Like his film.

But back to Mr Wrong. In our darkest hour, it’s Bill Gosden we turn to. Despite a lukewarm Variety review from Mike Nicolaidi (who later made it up to us big time), Bill got it. Not only that – he liked it. He understood exactly what it was up to and greeted it enthusiastically. Enthusiasm. This was new and good. He wrote that Mr Wrong was ‘a thoroughly spooky good time’ and programmed it. Five o’clock on a Saturday. I was a bit put out. Why not a more prestigious slot, like opening night? But he wouldn’t budge. And he was right too. The best festival directors know their audience.

When we turned up outside the Embassy Theatre (capacity of around 800), the crowd in the foyer was a scrum. I thought the doors hadn’t opened, but the theatre was already seating, and the teeming throng were the punters who wanted to get in but who hadn’t booked. Of course, most of them were my mates. A full house can be stressful for a filmmaker. It’s a rule of nature that the people you care about most are the very ones who turn up late without a ticket. Some were holding $10 notes above their heads, a bit like auctioning seats on United.

I was absolutely knocked out. After the many rejections, this was the opposite to a hairball in your throat. But no time for tears as the start time approached. Mr Wrong has a stunning musical overture by Jonathan Crayford, so everyone could finish their ice creams and listen as the lights dimmed. Let the show commence.

Sharing your film with the first audience is a terrifying and thrilling experience. You sit there facing the screen, but you would be better with a chair beside the screen watching the audience.

Gaylene, Gary Stalker, Trou Bayliss and Alun Bollinger (photo by Thom Burstyn)

The first Auckland screening of our little comedy thriller was a week earlier, in the mighty Civic in Auckland. The Civic was not as mighty then as it is today. Along with all the great theatres, it had fallen into disrepair. Its gold paint was peeling and the blue lights in the panthers that guard the ornate proscenium arch had been dark for years. To get onto the stage I had to walk a wooden plank over the yawning dark of the orchestra pit. Balanced on the railing at one end with the other on the stage, the paint-splattered plank wobbled the second I put weight on it. Could I come around the backstage area? No. There was a fire curtain up. At this moment I was grateful that I hadn’t accepted any of those pre-screening whiskies I had been offered. I walked that plank with my heart in my mouth, wondering how the hell I was going to get back once the film started. It seemed to take forever to get to the stage to turn to face that first expectant crowd.

I did not feel like Michael Thornhill. I felt small and silly. How could I have been so audacious as to think I could present myself as a proper filmmaker – one of the gang? I wasn’t Roger or Geoff or Vincent. What if those smiling excited faces turned to not excited at all? I was convinced they wouldn’t like it. All indications were that this could be my first and last sortie into dramatic storytelling. Should we have stationed people on the doors to lock them all in? However, just when all seemed hopeless, those childhood elocution lessons kicked in. You put your feet on the ground, and you breathe and slow down. I can’t have been very convincing though. One article in the Auckland Star described me as ‘a skinny little bookworm in blue jeans’.

And they also described the film as having a standing ovation. I must admit it was pretty awesome. The crowd began laughing early on and the laughter grew more and more hysterical, until at one moment towards the end the Civic erupted in a big laugh followed by an ear-piercing scream. The sound of grown men screaming in the movies was something I hadn’t heard before, and I’m here to tell you there can’t be too much of it. The rest was a blur. I thought that some people were sitting down clapping while others were standing up to put their coats on, but once it was in the Auckland Star – a standing ovation it was ever after.

Joe Moodabe had said that if it did all right in the Film Festival, Amalgamated would look at distribution. ‘At last,’ I thought. ‘At last we will get this film all the way to Invercargill.’ We steamed down the country in the festival, packing it out all the way to Dunedin. But no. Amalgamated said that we had ‘stacked the audience’ (meaning we filled the seats with our friends), and anyway, now too many people had already seen it. This is just plain silly – well, it was in the case of Mr Wrong – but those sentiments live on today. You need to know that distributors still hold very firmly to these opinions despite all evidence to the contrary.

By July 1985, though Lindsay Shelton had sold Mr Wrong all over the world and we were completing the US deal, we were still on our own as far as our home territory went. However, there was one stone left unturned. Masters Cinemas was a very small chain, owned and operated by Lang and Maureen Masters. They had two theatres in Christchurch and one in Wellington. Not exactly a national reach, but beggars can’t be choosers, can they? Their Wellington theatre was small with no street front in Cuba Mall above a Jazzercise club. It was managed by Kerry Robins, co-producer of Goodbye Pork Pie and Utu, whose sisters, Pat and Veronica, I have told you about. Being married to Bruno Lawrence and Geoff Murphy, they worked tirelessly for their husbands. They mothered the Murphia – the tribe of Murphys, Robinses and Lawrences who continue to populate crew lists. Kerry took on Mr Wrong with enthusiasm, if not a little guilt. He was vaguely implicated in the episode that got us tied up in the High Court.

Nevertheless, Kerry is whānau, and had been instrumental in making Goodbye Pork Pie an enormous success, and I was sure he would make Mr Wrong a memorable splash – even if it was with only one print in one cinema. The marketing budget was pretty well non-existent but, fuelled by our Film Festival success, Robin and I managed to line up a veritable tsunami of national-reach publicity, including the cover of the New Zealand Woman’s Weekly for Heather Bolton. A date was set. Friday September the 13th. On top of the WW, we had an article in the Listener with a good review, and I had designed and hand screen-printed a hundred posters with Chris McBride at the Media Collective. We had three thousand flyers printed with the opening date on them, ready to go into letterboxes. All set.

When the phone rang, I was putting flyers in envelopes to post to schools. Kerry sounded shell-shocked when he delivered the bad news. The cinema was closing immediately. The Jazzercise club had bought it. Masters was closing up shop at the end of the week. I put the phone down and just sat there stunned for a very long time.

Jan Fisher (front) and Heather Bolton (right) hanging washing (photo by Clare Clifford)

There was only one place left – the Paramount on Courtenay Place. On the bright side, it was well-positioned, and it could take six hundred-plus punters. It came alive at Film Festival time, but for the rest of the year it sat sadly on Courtenay Place, screening soft porn in the afternoons. It was owned by Merv Kisby who had a second, more successful, suburban cinema in Brooklyn. The Penthouse was one of the last family-owned and run cinemas in the country. But Merv was put out. He wasn’t happy that we had put our film with Kerry. Not that he had uttered a word to make a bid. But when the Masters deal fell over, he wasn’t in a hurry to return our calls. We just couldn’t get to talk to him. His office was sympathetic, but he was clearly not answering our phone calls or coming to our party. Time was ticking by and there was only one option left – we were going to have to make him an offer he couldn’t refuse.

We needed to buy his cinema for a week or two and get this film launched. It’s called ‘four walling’. Not unheard of, but hugely risky. The producers rent a cinema for a season and take the financial risk. They cover all costs and pocket the profit – if any. We were running out of options fast. We had to secure the Paramount for Friday the 13th. The date was in black-and-white in the Woman’s Weekly and the Listener.

I knew Merv was a gentleman of habit. Every weekday at five o’clock he would cross Courtenay Place to go to his friend’s record shop. They’d lock up and go to the pub.

At quarter to five one wet Wednesday, I lurk behind the record stacks. His mate knows I am there with no intention of buying, but what can he do? I hunch down and wait. Sure enough, in comes Merv. I leap out and greet him like a long-lost friend.

‘G’day, Merv! I’ve been trying to reach you,’ I say, with more confidence than I am feeling.

Caught on the spot, he mutters a gruff hello.

‘You will know we are looking for a theatre to screen our film in. How much for the Paramount for two weeks, starting in ten days?’

Merv doesn’t really want our film in his cinema. We will be a nuisance, he is sure. But the thought of some actual cash is too much for him. He names an astronomical sum. By this stage I would accept any price he utters.

‘Six thousand dollars.’

I stick out my hand and look him in the eye, beaming, ‘Done.’

He hesitates, then shakes on it and immediately goes into reducing what we are buying. We could have his projectionist and one ticket-seller person. That will be it. We’ll have to look after the cleaning. Cleaning? The least of our worries. All that floor-scrubbing and dusting of dressing tables we did for our mothers in our childhoods was going to come in handy after all.

Next morning, he hit the phone.

‘Do those girls know what they’re doing?’

You can be pretty sure what the answer was.

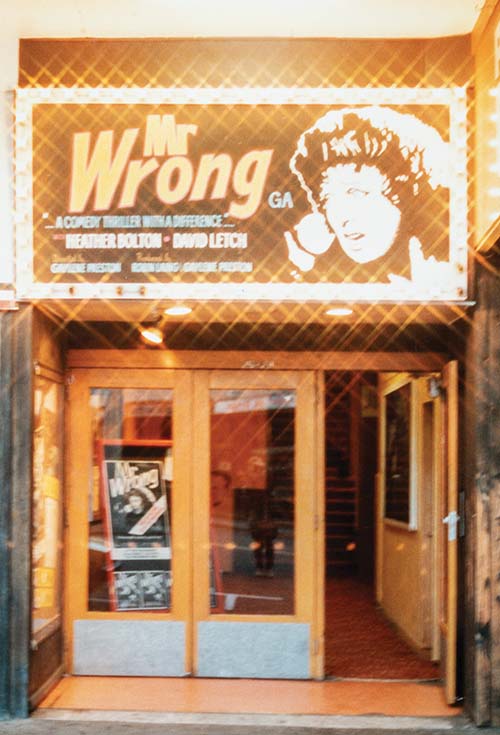

So that’s how I ended up holding the ladder pulling down Danish Dentist on the Job from the Paramount front hoarding to replace it with our brand-new billboard for Mr Wrong. We tested every light bulb while a small army of schoolkids did a letterbox drop of Mount Victoria – it was our friends who wanted to see it when all was said and done – and every journalist that turned up to interview us wanted to know why we were launching this festival hit in the porno picture house. So we told them. I got a letter from Sir Robert Kerridge asking me to cease and desist from spreading misinformation about them in the media. He was fairly famous for never putting anything in writing, but this letter was from him not a lawyer, because he knew I hadn’t. I had just broken the big secret deal that keeps us filmmakers in pubs complaining – if you do them down publicly, your next film has no show. That’s the fear. Well, given how hard it had been to make this one, I wasn’t thinking of making another, so I was fearless. But the bullies rule. The Weinstein factor.

The day we opened, we went down to the cinema half an hour early to find a queue already stretching to Cambridge Terrace. Holy cow. We’re in the money. But when we got to the top of the stairs, there was hardly anyone seated. Merv’s box office woman was multi-tasking, selling a ticket then rolling an ice cream, selling a ticket then rolling another ice cream. We pulled up our sleeves and quickly mastered the ancient Kiwi art of making chocolate-dipped ice creams, and the session started almost on time.

The film took off, and everyone did indeed have a very spooky, very good time. We returned $11,000 plus that week, and grew the take in the second week. Merv took our film on, and we even ordered a second print for his far more respectable Penthouse.

I was thrilled about this. The Paramount had two very old carbon lamp projectors that were antique even for 1985. This means that the light fades over time, and if the projectionist isn’t onto it, the screen can go entirely black. This happened a couple of times during our Paramount season. I found out by accident. My neighbour, Meriol Buchanan, an actor I knew, plays a small part in a scene where she turns up to buy the car but her dog won’t get in it. She got a couple of complimentary tickets and went with her daughter, who worked in the industry. I came across her at the supermarket and said how much I had enjoyed her performance. A cloud crossed her face, then she said, slightly querulously, ‘I suppose that was an artistic decision with that scene, to not see me. An artistic decision, the sound but no picture.’

During the screening, the screen had slowly faded, going black just before her scene. It lit up again immediately afterwards, when the projectionist replaced the carbon lamps. If the film wasn’t haunted, it sure as hell had a life of its own.

The other thing about the Paramount projectors was that they worked in parallel with one another. When one twenty-minute roll ran out, the other projector took over with the next one. This led to a lot of film handling. Sometimes the beginning and end of print rolls would sparkle like sandpaper. The Penthouse, on the other hand, had a platter. The film gets loaded onto one huge horizontal plate and hangs in space as it winds through the projector gate before rolling onto the other plate. At the end of the process the film is ready to be threaded up for the next screening. Far less damage. No rewinding, no handling. I hadn’t seen the second print, so I went up to the Penthouse to check it the first time it screened.

I slouched in my seat among an excited six o’clock audience of suburbanites, looking forward to the first time I would see the film without a roll change at twenty minutes. Away we went. I was feeling really pleased with how it was looking when, right at the roll change moment, the image froze and Mr Wrong melted in the gate and burnt.

Silence. The lights came on. I leapt out of my seat and went up to the projection booth, where Merv was none too gently hacking at our pristine print to splice it together and shove it back onto the platter.

‘It’s never happened before,’ he told me.

I hate it when someone tells me that, but this is what he said happened. He is indeed a man of habit. After he set a film going and all was well, he liked to eat an apple. When he was finished, he always threw the core out a little top window in the projection room onto the street below. In this case, the core had bounced on the window frame, ricocheted back, hit the film hanging on the platter and dislodged it, so it stopped. Hence the freeze and burn. Heath Robinson, eat your heart out.

Should we, right at the beginning, have had the film blessed – before it was even a mark on a piece of paper? Was the title a jinx? Was the ghost of Mary Carmichael actually embedded in it? Well, if it was, she has a great sense of humour. The film travelled the world, and I heard that dogs in the cinema at the Munich Film Festival growled at the screen every time David Letch – who played the villain – came on. And when it went wrong, it always went right. A young distributor, Mark Christiansen, picked up the film and it screened in the Academy Cinema in Auckland for seventeen weeks, ‘right up the arse’ of Kerridge, according to John Hart, who ran the theatre.

I popped in to see him during the season. We were chatting in his foyer when his ears pricked up and we heard that laughing, blood-curdling scream emanating from the cinema.

‘They’ll be out in twenty minutes,’ he said, and put on the coffee pot.