Grand Tour is a beautifully aloof film, adrift from time and space

The critically acclaimed and award-winning Grand Tour is a wonderfully strange experience. Luke Buckmaster dives in.

Portuguese auteur Miguel Gomes’s new film Grand Tour has a beautifully aloof way of capturing cities, feeling out of time and out of place. Like its protagonist Edward (Gonçalo Waddington)—who doesn’t want to marry his fiancé, so he flees, embarking on a voyage across Asia—the production, which won Best Director at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, is adrift and enigmatic. It appreciates fine details, conjuring many compelling images and moments, but also has a vague shape-shifting quality, vaporous and cloudlike—as if the film is forming and reforming in front of our eyes.

It’s a period drama, of sorts, beginning in 1917 in Myanmar (still called Burma at this point), though Gomes’ isn’t too concerned about historical accuracy. Sometimes quite the contrary: in one scene for instance a man in a Manila karaoke bar sings Frank Sinatra’s My Way, which was released in 1969. Nor is Gomes concerned with plot, or even plot momentum. Instead of following a straight linear line, the film seems to travel in zigzags, stepping to the side of reality—in the moment but not quite there, or there, but not quite in the moment.

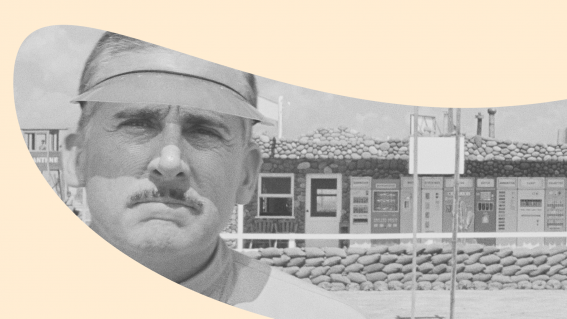

Opening images of a fairground set the visual tone: documentary-esque but also lyrical and slightly surreal. A narrator informs us that Edward hasn’t seen his fiancé for seven years, and struggles to even remember her face. Early on there’s a forlorn shot of him standing in the rain, getting soaked, holding a bunch of flowers, again typifying the sorts of visions we’ll see going forward. Most of the film is presented in smoky monochrome—coarse, grainy, misty—like it was shot in the glow of moonlight, though every once in a while it switches to colour for no discernible reason.

Given how well Grand Tour works as a mood piece, and its unconventional approach to narrative, one hardly feels inclined to describe the story using twee turn of phrase like “finding yourself,” though there’s an element of that. Edward says, at one point, “I lost my nerve and ran away.” His fiancé Molly (Crista Alfaiate) follows him; she has soft features, looks like a silent film star, and becomes more prominent in the second half. Molly’s pursuit stresses Edward out, but that anxiety isn’t really passed on to the audience: you don’t feel the intensity of his circumstances. Even when we’re close to the protagonist, sharing his space, it feels like we’re observing him from a distance.

Edward tallies up various countries during his “grand tour”—travelling to Singapore, Thailand, The Philippines, Vietnam, Japan and China. Depictions of various cities, including Shanghai and Tokyo, feel paradoxically both fresh and old, like the film has assumed the mindset of a person returning to a familiar city they lived in a long time ago, caught between observing what it’s become and remembering what it once was. This is where the film moves: in a dreamy space between real and actual, present and past. Gomes is drawn to scratchy edifices and images of nature, visions of which creep into more modern, city-based environments, giving them an almost spiritual hue.

There’s lots of lovely flourishes, some of which come out of left field but still feel like parts of a smooth cohesive whole. One occurs about 30 minutes in, when we see a young man singing on the street in Saignon. This shot is fused with visions of dancing and festivities, the scene existing in two moments swirled together. These sorts of mashed up images have been deployed in cinema countless times before, though this particular flourish reminded me of F. W. Murnau’s use of expressive montage in his 1927 masterpiece Sunrise: A Song of Two Humans, combining visions of bustling nightlife with the feelings and thought dreams of the characters.

Watching Grand Tour is a little like experiencing a trance. And not your average, mind-numbing, quack-induced trance: it’s a nice, lovely trance. This film has no sharp edges, and not all of it makes sense or follows a decipherable logic. That’s part of the appeal.