How A Star Is Born is making Hollywood great again

If you consider that it’s been over 40 years since the last iteration of A Star is Born—the film having been reliably produced every two decades since the 1930’s—Bradley Cooper’s just-released remake starring himself and Lady Gaga is practically overdue.

This latest adaptation makes four versions to date of the film (or five if you include an extremely similar picture called What Price Hollywood? made in 1932 by George Cukor). Previously: William A. Wellman’s 1937 original; the 1954 Judy Garland remake, also directed by Cukor; and most recently the 1976 Frank Pierson-helmed Barbra Streisand vehicle.

Though minor details have of course changed, throughout each of these translations the main elements of the plot have remained remarkably intact: A woman, brimming with tragically untapped talent, is plucked from obscurity by a successful, powerful (alcoholic) man. Seeking to both court her romantically and cultivate her professionally, he ensures that her star quickly rises. As she ascends, however, he falls. Melodrama and misery ensue, culminating in a tragic, cathartic crescendo.

In 1937, Janet Gaynor’s North Dakota farm girl Esther Blodgett aspired to be nothing more than an actress; when the film was remade 17 years later as a comeback vehicle for Judy Garland, Esther became an equally talented singer and dancer; In 1976 the acting part went out the window altogether, with Barbra Streisand’s Esther Hoffman, an undiscovered lounge singer turned rock star.

Now in 2018, the role has morphed into Gaga’s waitress-with-the-voice-of-an-angel Ally (who has no last name, apparently), an ordinary girl whose music career has so far been hampered by the size of her nose. When Jackson Maine, a flailing rock/country perpetually drunk singer shows up and says “but I think you look great!” (or words to that effect), however, they fall in love and she rockets to stardom.

At a time when we’ve all just become painfully aware how many Hollywood careers are the result of transactional sexual and romantic relationships, one could argue, A Star is Born is a risk; even more so when you consider that the Marvel movie-consuming public aren’t exactly used to spending 2 hours staring at peoples faces in extreme close-up while they do little other than sing and cry.

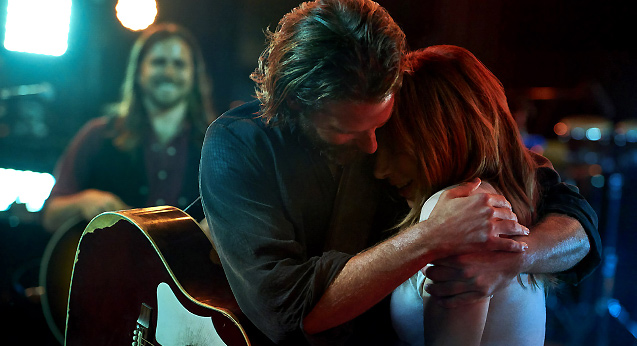

Yet, as many, many reviews have noted, for the most part, this amounts to an unexpectedly decent—and wildly popular (see the weekend box office figures)—cinematic experience. With much credit going to Gaga and Cooper’s fine, naturalistic performances and a selection of actually good songs, it is also a fantasy: one where success corresponds with worth; where fame, talent, and artistry are connected; where all-consuming, toxic, codependent relationships are romantic; and (perhaps most unbelievably) where alt-country is wildly popular.

For a self-serious actor (and now ~auteur~) like Cooper and a notoriously self-aware performer like Gaga the attraction is clear—these roles are the perfect vehicle for not only prolonging lore and inciting nostalgia, but also for pushing a new agenda: the idea of authenticity.

Every version of A Star is Born has been made as a restatement and reinforcement of certain values, and with every new iteration these are re-calibrated and warped to suit the industry that is itself apparently being critiqued.

Here, as cynical and destructive as Hollywood may seem, there remains an inherent dignity, even nobility to Ally and Jackson’s individual talents. Where, in the previous films, the male lead is undone by jealousy and emasculation in the face of his far more successful spouse, Jackson is instead merely disappointed that Ally gives in to the demands of her slick British manager and sells out to mainstream demands. Coupled with his alcoholism and a tedious tinnitus subplot, this version of the character portrays stardom as a kind of tortured, soulful artistry while also making palatable what is not really the healthiest relationship.

It’s a romantic reframing to be sure (particularly compared to Kris Kristofferson who unloads a firearm at a helicopter and bangs a random journalist trying to snag an interview with his wife) but the effect is deeper than just endearing us to Cooper.

By eliding the melodramatic angle of jealousy and competition between the couple, and recasting their pain as an indication of creative genius, another layer is added to the Hollywood myth that lies at the heart of A Star is Born—and in doing so, Cooper indulges not only his own nostalgic fantasy but ours.

However much grit and realism are ostensibly injected into the world of celebrity here, it is still brimming with old Hollywood romance. While compared to its predecessors, the 2018 film advances things stylistically and aesthetically (Cooper loves his extreme close-ups and lens flare) and pays brief attention to signifiers of the modern world (YouTube is referenced once, Halsey briefly cameos) such temporal markers are kept to a minimum.

Instead, the world outside of the central relationship barely even seems to exist—a lack of context that renders things weirdly timeless, placeless and apolitical. Money, influence, even Ally and Jackson’s uneven dynamic are not even really acknowledged. That stuff, Cooper seems to say, is trivial—as if we haven’t all just been reminded that the power imbalance between a young, unknown woman and a famous, wealthy, and deeply troubled man a decade her senior is not insignificant.

In fact, the easiest critique to be made of Cooper’s A Star is Born is that, compared to earlier incarnations, Gaga’s female lead has perhaps the least agency out of any of them. Feisty and fiery in the film’s first half, by the second she is barely a feature, baffling Jackson with her sudden commercialist bent and acting on the instructions of whichever man happens to be around her at any given time. Jackson meanwhile is a noble figure, by the end basically martyred in exchange for his spouse’s success.

Retrograde as they may be, however, for Cooper these issues are distinctly non-political—the Hollywood experience, the sanctity of stardom exempt from the banal complexity of contemporary values. Arguably, for audiences, this is the fantasy: here amnesia is a relief not a concern. Just like in the golden days of Hollywood, the film is an escape—an influx of over the top emotion over a particularly drippy couple a welcome respite from not only the increasingly elaborate and ubiquitous ‘cinematic universe’ but also from our own lives.

2018’s A Star is Born is the ultimate fantasy because it willfully forgets everything one might think its predecessors—and our own troubled times—have been trying to tell us. Instead, it imagines authentic artistry as synonymous with stardom, a selfless expression of the soul sent into a thankless void.

Like the film itself, while this thought is on the surface a bit of a bummer, it’s not hard to see the appeal.

With celebrity increasingly democratised, and the industry itself looking increasingly poisonous and corrupt, A Star is Born is like an allergic reaction to such transitions, and an appeal to a desire that Cooper makes cannily universal: To make Hollywood great again.