How are the Oscars chosen? Answer – it’s complicated

We pull back the curtain on Academy Awards voting.

Every year, there’s much discussion about the Academy Awards—who should win, who did win, and who didn’t even get so much as nominated. It’s not interesting to everyone, sure, but we’ll take it as gospel that you are here so you can better understand the process.

The Academy of Motion Pictures & Sciences is made up of some 7000 film professionals. It’s an organisation divided into branches—the Actors Branch, Cinematographers Branch, Costume Designers Branch and so on. Each member belongs to just one branch, and they’re the sub-groups who determine each nomination. For instance, it’s not the whole Academy you should hold responsible for not nominating Little Women’s Greta Gerwig or The Farewell’s Lulu Wang for Best Director—that one falls on the shoulders of the Directors Branch.

Having said that, it’s not unfair to critique the diversity of the Academy overall. To their credit, they’ve responded to criticism about this in recent years, working to expand their member roster. In early January, 842 new members from 59 countries were invited to join. Of these invitees, 50 percent of whom were female and 29 percent people of colour. This follows large numbers of invitees in recent years, including over 900 in 2018.

As the Hollywood Reporter notes, “It is unclear how many members the Academy has in total. If all of those invited last year accepted invitations, the organization would have 9,226 members, not including this year’s class. As of 2019, the organization disclosed that 32 percent of its members were female (up from 25 percent in 2015) and 16 percent were people of color (up from 8 percent in 2015).”

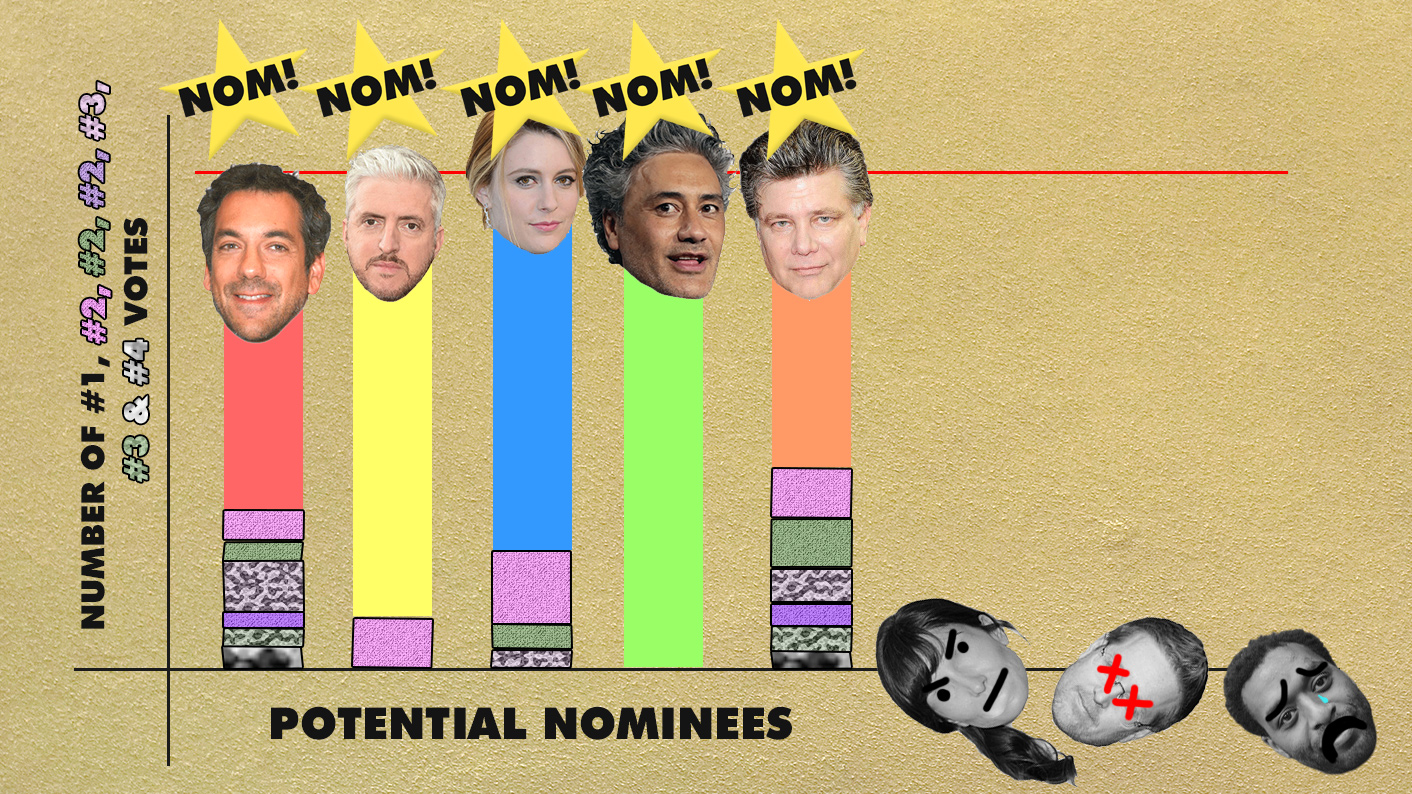

But back to the Oscars. Generally speaking, each branch follows similar rules to finalise the nominees in their respective categories. Accountants PriceWaterhouseCoopers have the perhaps unenviable task of overseeing a complex preferential voting system that sees editors rank their picks of editors, actors ranking actors, and so on. All voting members of the Academy are eligible to select Best Picture nominees, which also uses the preferential voting process. The intention with preferential voting is to reward films with a small but passionate number of supporters over films that just get heaps of #3 or #4 positions on voting forms.

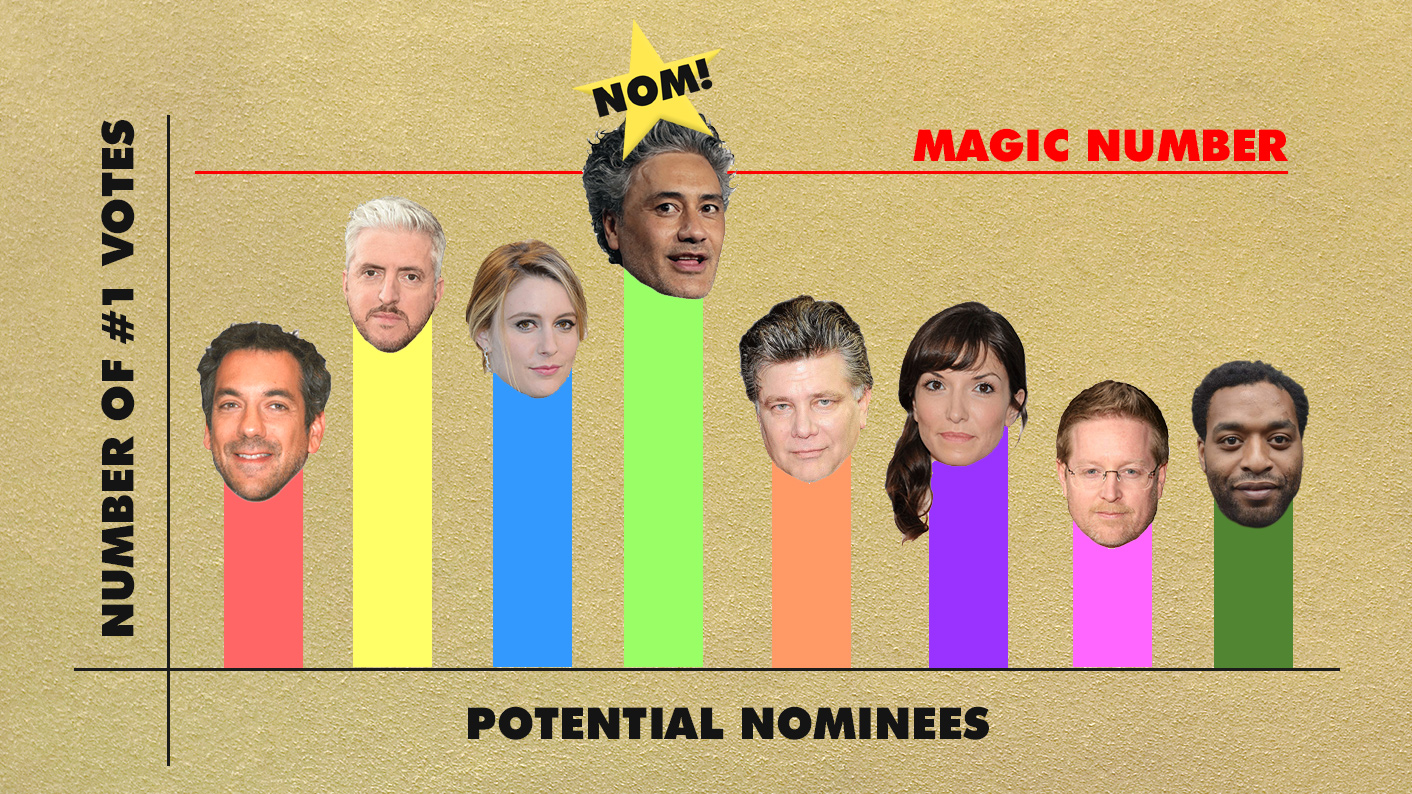

Here’s how. Once the ballots are in, for each category PriceWaterhouseCoopers calculate a “magic number”, which is the total number of ballots received in the category, divided by the number of potential nominees plus one.

Say 501 ballots were received for Best Adapted Screenplay. With 5 nominees for that category, the accountants divide 501 by six (five potential nominees plus one). That equals 83.5, rounded up to 84, which is the “magic number”.

The ballots are placed into piles based on the first placed choice. One pile will have all of the Best Adapted Screenplay ballots that have Taika Waititi in first place, another pile has all of the Best Adapted Screenplay ballots that have Anthony McCarten in first place, and so on.

If any of these piles are greater than the magic number (in this example, 84 votes), that film becomes a nominee and the ballots are set aside. So, if Waititi received 94 #1 votes, he’s in and those ballots are no longer considered.

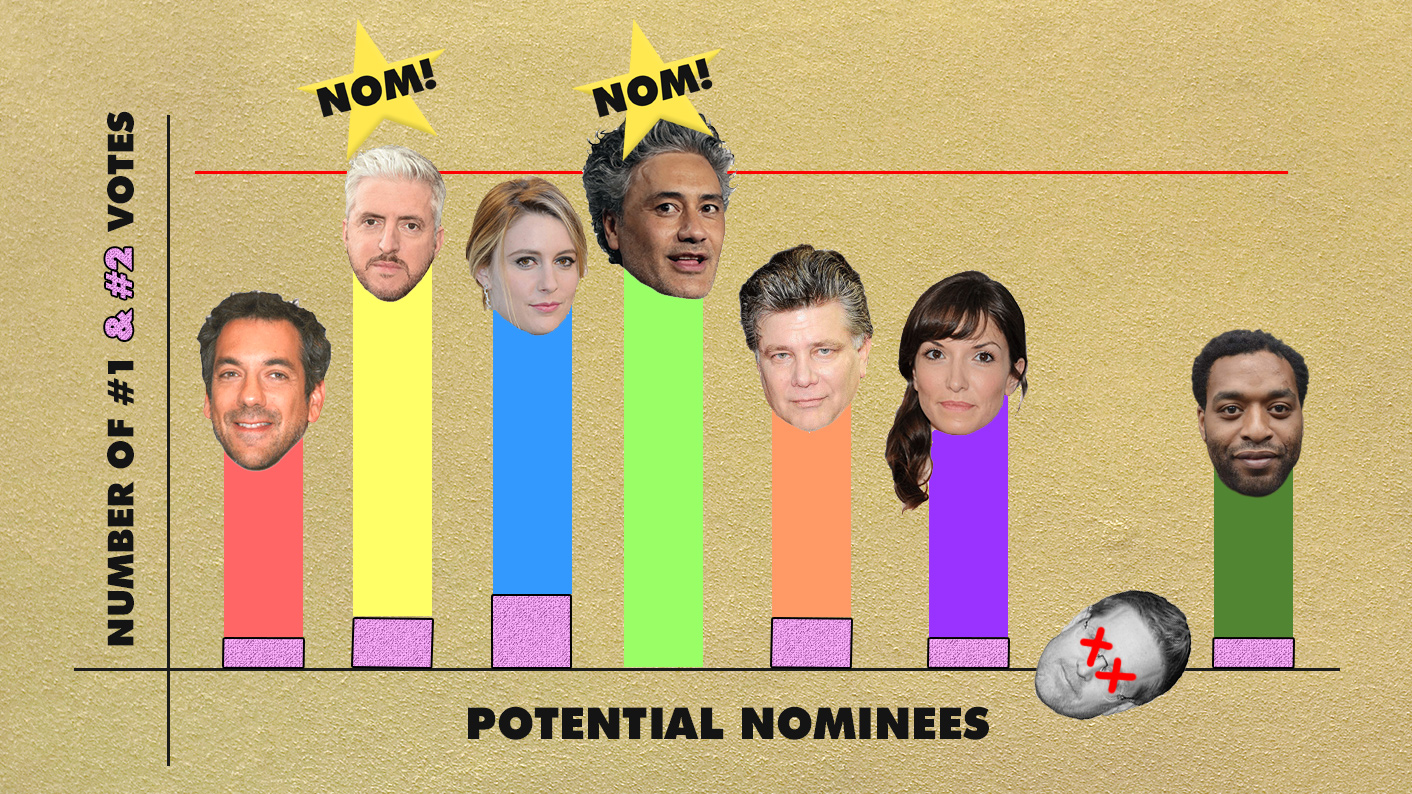

Next, the prospective nominee with the fewest first-placed votes is eliminated from consideration, and those ballots are redistributed based on those voter’s second-placed choices.

Say Anthony McCarten was stuck on 74 #1 votes. These ballots on which he’s ranked #2 are then added to his pile, pushing him closer to the magic number and being nominated.

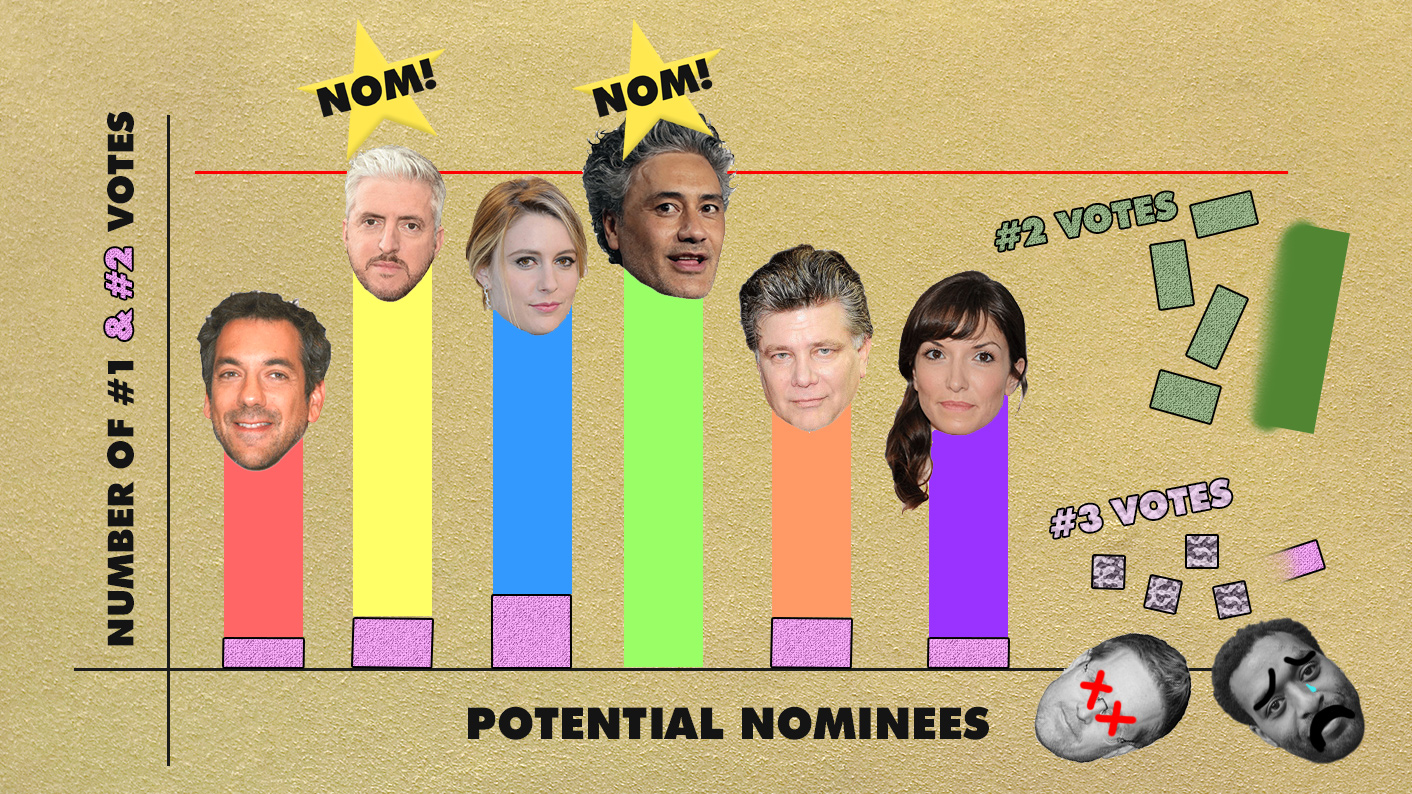

This process gets repeated, over and over. The ballots with fewest first-placed votes (the smallest piles) will one after another be redistributed to other piles based on the voter’s third, fourth or fifth choices as needed.

By ranking in the middle, or lower, on voters’ ballots than films that only received low vote totals and were then eliminated, other potential nominees can end up with these ballots and hit the magic number.

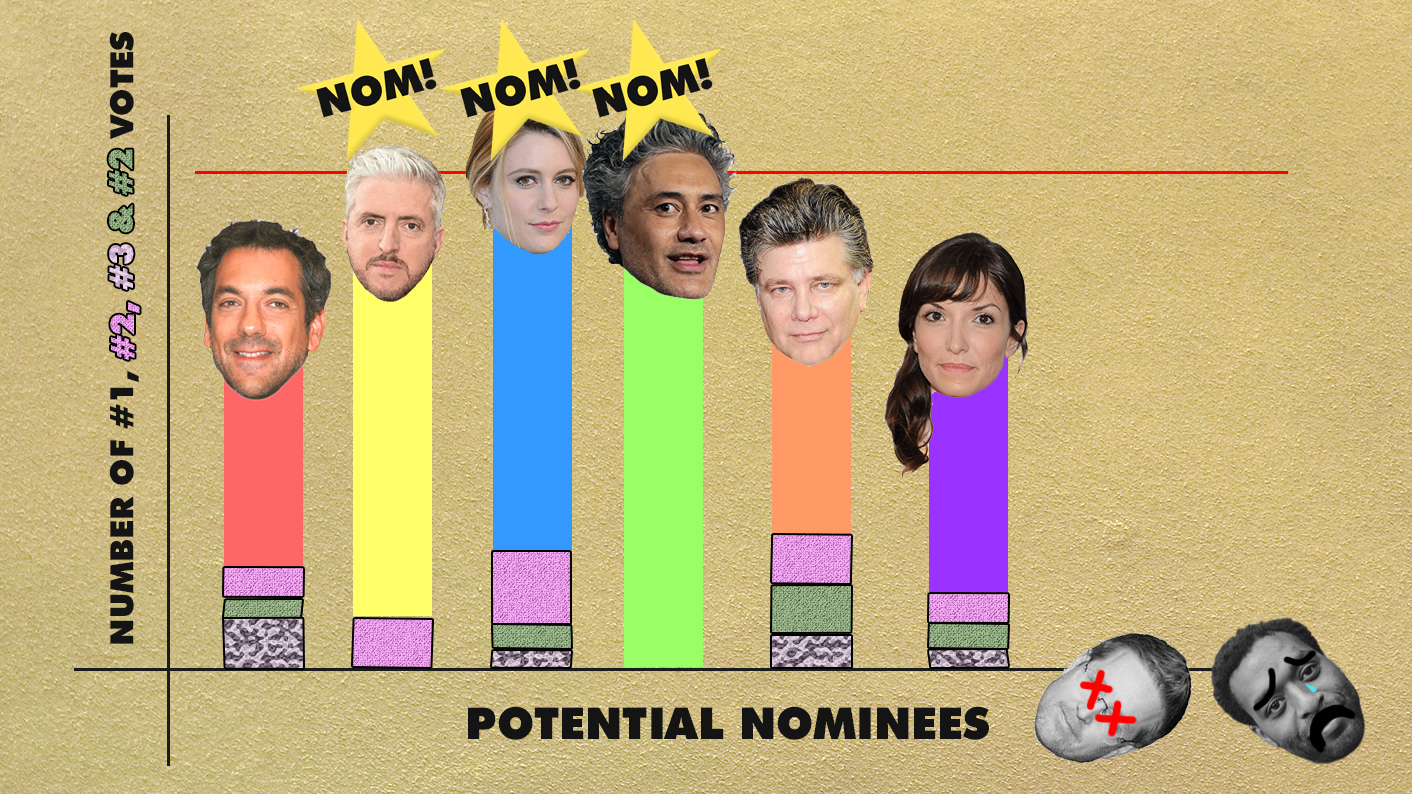

Nominations are finalised when five nominees hit the magic number (which is recalculated throughout the process as ballots are voided) or when there are only five nominees left in contention.

Are you still with us? Spare a thought for those who have to oversee this process for each category. It’s even more complicated for Best Picture, because every Academy member can vote (as opposed to just the Actors Branch voting for actor nominations etc) and because there’s a greater number of nomination slots.

So, that’s the nomination process in general. There are a few departures from this. The official rules provide that “Each branch or other designated committee shall be permitted to formulate its own special rules, provided the final ballot presents not more than five achievements in each category, and that nominations and final voting in each category are restricted to active and life Academy members.”

The International Feature Film award (previously known as Best Foreign Language Film), for instance, has a different shortlisting process: “The Phase I International Feature Film Committee will view the eligible submissions in the category and vote by secret ballot. The group’s top seven choices, augmented by three additional selections voted by the Academy’s International Feature Film Award Executive Committee, will constitute the shortlist of ten films. The Phase II International Feature Film Committee must view the ten shortlisted films and vote by secret ballot to determine the category’s five nominees.”

Likewise, Short Film Awards and Best Makeup and Hairstyling are examples of unique shortlisting processes, but still utilise the preferential voting process. Interestingly, both of these selection processes require voters to have seen all of the films shortlisted in order to vote on the final nominations (you’d think this would be the case with all categories—but no).

That’s the process taken to get to the full list of 2020 nominees. The good news is that—for the most part—voting for the actual Oscar winners is a straightforward ballot. It’s not restricted to branches, so actors can vote for Best Editing, writers can vote for Best Director etc. It’s a big ol’ democracy. Each voter gets one vote per category, with little requirement to have seen the nominees (Short Films and Documentary Feature being exceptions to this, though we suppose some people just lie through their teeth and say “oh yeah, I saw them all”).

Best Picture is the big exception. That’s the only category in the final ballot that uses preferential voting. That’s how a film can swoop in and win Best Picture against the flow of the night. In a polarising field, a film scoring a few #1 spots and mostly 2s and 3s after that has a fighting chance against other nominees that are love or hate. Consider Parasite vs Joker through this lens. Hopefully all that explanation above about the preferential process will make your Oscar tipping this year for Best Picture more successful, and explain the eventual winner.

Now go and have a stretch, hydrate, get some fresh air. We—and the Academy—have kept you here for far too long.

The Oscars take place on Monday afternoon, February 10 (NZ time). You can watch the awards ceremony on TVNZ Duke.