Amy Poehler brings inescapable teen averageness to life in Duncanville

Amy Poehler voices both a teenage boy and his mother in new animated sitcom Duncanville – watch it now on Neon. Liam Maguren digs into a moment of enduring personal shame to highlight how much he reluctantly related to this tale of constant—and hilarious—punishment by the puberty gods.

One school trip, we were taken to a local ice rink. Us kids were instructed to skate in an orderly circle. If anyone dared to, they were allowed to break from the group and try to jump the ramp placed strategically in the centre. It looked intimidating, yet possible, so I skated up to the ramp confident and preparing for praise from my peers, only to bail like flung pizza dough in front of their judging eyes.

Here’s the thing about landing flat on your back in an ice rink: you don’t stop. The lack of friction means you can’t do anything until you come to a halt, leaving you at the mercy of momentum. I’ll never forget that ten-second slide of shame.

See also:

* Everything new coming to Neon

* All new streaming movies & series

I share my tale of Icarus to highlight how much I reluctantly related to Duncanville, Fox’s new adult-targeted animated comedy about a painfully average teenager whose attempts at being The Man is constantly—and hilariously—punished by the puberty gods.

The first minute of episode one wastes no time embarrassing Duncan in his own dreams. Out-climbing Alex Honnold during a free solo of an imaginary rock face called The Devil’s Ass, the noodle-armed Duncan proudly declares: “The mistake everyone made was training, that’s why I didn’t.” This unearned hubris rings pathetically true in the mind of an unspectacular teenage boy, as does the moment where he (almost) makes out with Wonder Woman.

The show’s focus on Duncan and his inescapable averageness drives Duncanville, setting it apart from similar animated series about nuclear American families. While the rapid-fire pacing of its humour will feel familiar to fans of Fox’s similar hits like Family Guy and Bob’s Burgers, the gags and stories have a distinctive slant thanks largely to Duncanville‘s three creators.

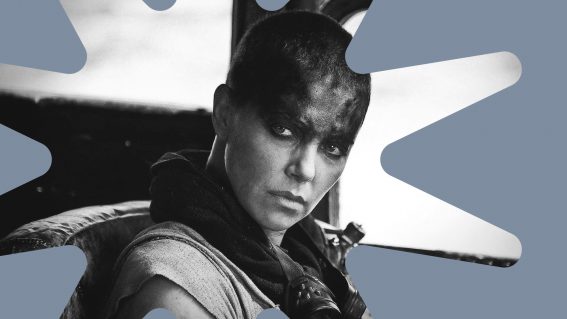

The most bankable name is comedy superstar Amy Poehler—co-creator, co-writer, and duo-voice actor on Duncanville. Channelling Nancy Cartwright’s legendary work as the voice of Bart Simpson, Poehler provides a superb mouth for the show’s leading lad. Had I not researched this beforehand, I wouldn’t have pegged Poehler as the not-quite-broken voice of Duncan.

Duncan’s mother Annie, however, is very obviously Poehler in the best way possible. Think Leslie Knope as a parking warden and you’ll understand Annie’s aggressive enthusiasm for both parenting and criminal justice. Naturally, the relationship between the fumbling son and the overprotective mother leads to many verbal tugs-of-war—a solo double-act that Poehler called “an existentially fun exercise.”

Duncanville‘s other two creators, Mike Scully and Julie Thacker-Scully, are arguably more prestigious names in the realm of American animation. The pair have been involved with writing and producing episodes of The Simpsons since the ’90s, cementing Duncanville in storytelling experience other off-the-wall comedies lack.

Don’t get me wrong: I love a good Family Guy chicken fight that lasts ten minutes for no reason, but it’s refreshing to see Duncanville not lean heavily on randomness and absurdity. There’s so much cross-generational angst for the show to explore that it doesn’t need to travel far from its focus for the sake of a good laugh.

Perhaps the angstiest of the lot is Duncan’s ponytailed father Jack, voiced by the lord of dorky dads Ty Burrell (Modern Family). With his heart tied firmly to pop culture of the past, Jack comes off as a kind-hearted pushover blissfully unaware of the changing world around him. It’s not that he’s in denial about no longer being cool, he simply unaware of it, making him the ghost of Gen X future.

Unsurprisingly, he can’t relate to his kids on a social level, let alone a social media level. Even when middle-child Kimberly offers to be her dad’s one and only Facebook friend, it’s “not from my real account, of course.” Jack’s quick to say “I’ll take it.”

Then there’s youngest Jing, merely a few years old, who shushes everyone to listen to a story on her news feed. Jack’s response? “Oh, that kid loves her Breaking News.”

Observations about generation gaps aren’t new, but Duncanville finds new ways to mock them. Importantly, every generation finds themselves the butt of the joke at some stage, so while it’s obvious to snicker at parents’ lack of technological finesse, it’s more universal to taunt a teenager for their lack of life experience.

By keeping its finger pointed at the latter, Duncanville stays locked on a painful but pivotal truth—most teenagers aren’t outstanding. And you know what? That’s OK. But instead of simply saying that, Duncanville seems committed to punishing its lead character for trying to prove otherwise. To me, a grown man still haunted by an embarrassing ice-rink incident from half his life ago, that’s good comedy.