A masterful Oscar Isaac brings uneasy charisma to Paul Schrader’s The Card Counter

Oscar Isaac, Willem Dafoe, Tiffany Haddish and Tye Sheridan star in Paul Schrader’s revenge-soaked gambling thriller The Card Counter – streaming on Neon. While it’s a much more controlled type of masculine turmoil, there’s certainly an echo of De Niro’s Taxi Driver performance in the way Tell feels constantly poised for an eruption, writes Rachel Ashby.

The Card Counter opens with a lush close-up of a card table. Emerald green felt, bright primary-coloured chips, and the Queen of Spades. There’s a little bit of grain and warmth to the camera. The whole thing feels tight and focused—all-consuming. Then there’s a pair of hands and a voice-over belonging to William ‘Tell’ Tillich, a former military convict turned professional card gambler, who speaks to the audience about learning to count cards during his ten-year incarceration. The music is slow, dark and brooding.

From the jump, there’s an ever-present tension throughout this latest feature by Paul Schrader (writer of Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, director of Blue Collar, American Gigolo, Cat People, First Reformed) that makes violence feel like a foregone conclusion.

Tell, the film’s protagonist, is a classic Schrader lone-man played with expert slow burn by the masterful Oscar Isaac. Like many other Schrader men before him, Tell narrates much of the film through his inner monologue. Sitting alone in anonymous motels, where he obsessively wraps all furniture in white cotton and butcher’s twine, Tell writes about his past in a small black journal. By day, he heads to equally desolate and nameless casinos where he wins small so that his card counting might go unnoticed.

It’s evident that Tell has something ugly in his past and that this comfortless routine is some sort of self-punishment. Isaac brings an uneasy charisma to this character that bubbles under the surface of his almost sociopathic restraint. While it’s a much more controlled type of masculine turmoil, there’s certainly an echo of De Niro’s Taxi Driver performance in the way Tell feels constantly poised for an eruption.

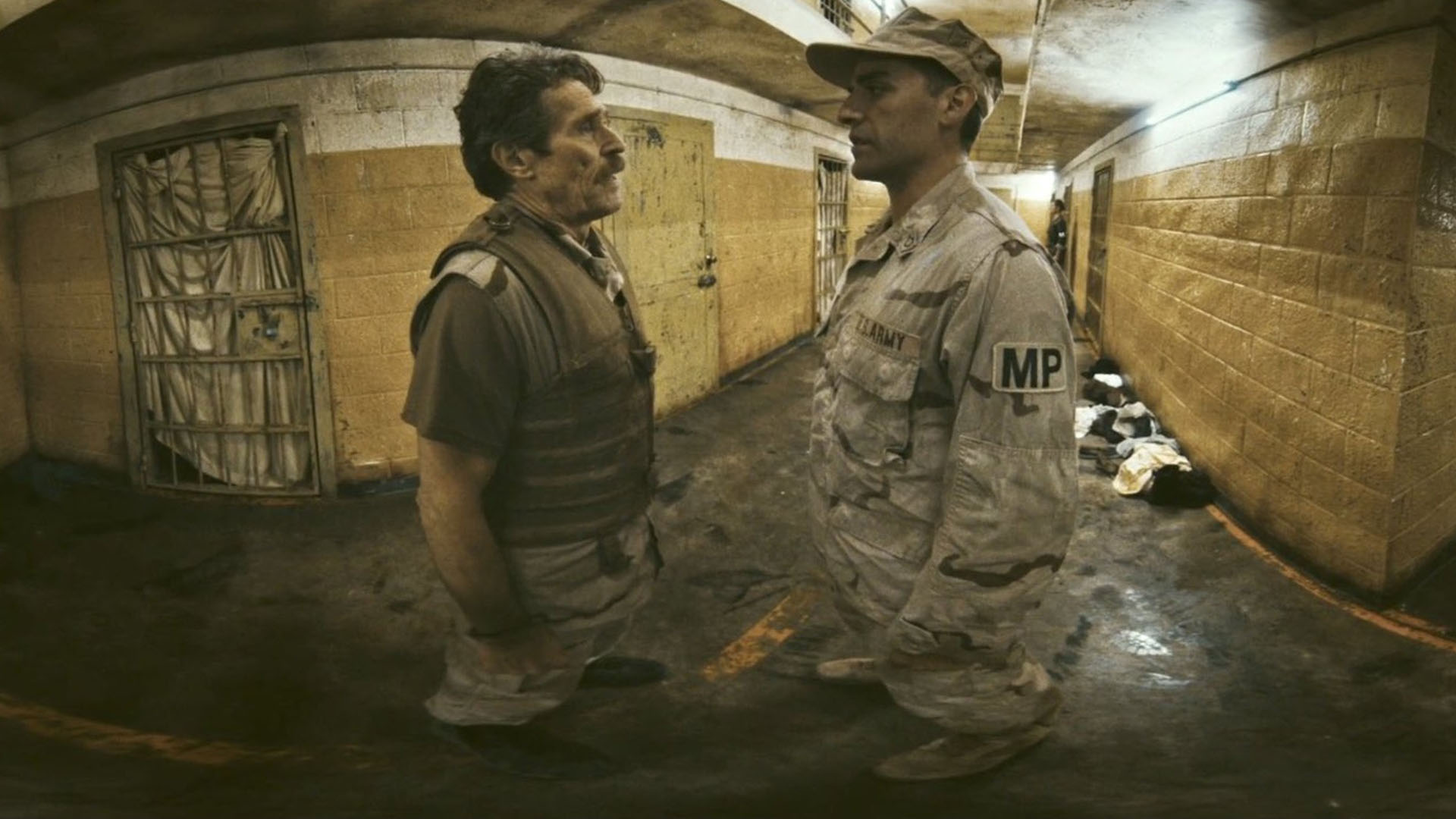

At one of these faceless casino complexes, Tell stumbles upon a seminar run by a Major John Gordo (Willem Dafoe) and we soon discover the reason for Tell’s decade behind bars. Gordo, it transpires, was Tell’s supervisor while he was a soldier involved in the brutal torture of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. Unlike his inferiors, Gordo walked away from those atrocities without consequence.

Tell’s nightmarish rememberings of the torture are some of the most visceral moments of the film. A wild fish eye lens roams the prison corridors to the sound of yelling, heavy metal music and barking dogs. The sprawling chaos of these scenes is a stark contrast to the tautness of the present day of the story. The violence is blunt and hideous. It’s horrible to watch, but impossible to look away.

Guilt and blame are arterial themes in The Card Counter. Tell struggles with his own agency, restricting himself with routine, and it’s evident that he feels the weight of his past actions heavy on his shoulders. The need to absolve himself of Abu Ghraib—or perhaps to just give someone else the chance to move on from its ugly legacy—is evident in Tell’s somewhat surprising decision to intervene when, at Gordo’s seminar, he meets a young man called Cirk (Tye Sheridan). Cirk holds Gordo responsible for the dissolution of his family: his father was also a soldier at Abu Ghraib who violently enacted his trauma on his family before eventually killing himself. Cirk has a very half-baked plan to kill Gordo, and Tell feels compelled to help him away from such a violent path.

There’s a fatalism to the construction of the film that makes this redemption quest feel doomed from the start. As Tell and Cirk travel together through middle-of-nowhere America the closeness established at the start of the film intensifies into claustrophobia. Each grubby, bleak casino with its empty sports bar seems identical to the last, creating a constant monotonous churn.

Within this grim setup, relative lightness is brought to the story by La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), a woman who runs a card stable which Tell agrees to join with a goal to finance Cirk out of his revenge plan. Haddish’s teasing and personable portrayal of La Linda are a good foil to Isaac’s outwardly phlegmatic Tell. Haddish and Isaac have great chemistry and their budding flirtation provides a brief but tantalising sense of hope. A scene where the pair walks hand in hand through a surreal light display is moving for its uniqueness in the film. It is a singular illuminated moment that feels ultimately dreamlike.

The conflict between personal accountability and structural inevitability is omnipresent. While Tell evidently feels he deserves to be punished as a “bad apple”, Cirk’s frustration is at the “poisoned barrel” of the American war machine. Conscription might have led Tell to be involved at Abu Ghraib but his self-loathing stems from the horror of discovering his own aptitude for violence while there. This awfulness is the rub that keeps absolution an impossibility for Tell. Because how can you move on from something as abject as torture?

As others have pointed out, much like Schrader’s 2017 feature First Reformed, The Card Counter has a notable Bressonian influence. There is a fable-like quality to the story which allows for certain leaps in the narrative that might otherwise jar. Tell and Cirk’s unlikely pairing works because we understand the bigger lesson Schrader is trying to impart about guilt and redemption. Tell’s purgatory life is unsustainable and an opportunity must be presented for judgement to be passed.

In many ways using a poker film to tell a story of war trauma is an obvious step for Schrader in his ongoing interrogation into the corruption of the American dream. You can play the game with skill and luck but, at the end of the day, the house always wins.