If You Make It…Will They Sell It?

The world of film distribution is, suffice to say, rather complicated.

Mind you, the world of movies in of itself is rather complicated. I still, to this day, have screaming matches with hapless film buffs who insist that anything with Steven Spielberg credited as an Executive Producer was somehow ‘guided by his talent’ as if he directed the damn thing himself.

But in saying all that, once a film is actually finished there are just as many ways to get a film seen by an audience (any audience specifically, not just a packed cinema crowd) as there are ways to get a film financed. The politics of distribution are nothing less than a radioactive hot-potato at the moment as this is specifically where issues like piracy, independent vs studio, arguments about money, censorship, release-dates, format, advertising and how-much-a-film-pisses-the-crap-out-of-its-audience comes into play. And on top of this there are some very interesting experiments going on in the world on how people get to see their movies, ranging from Kevin Smith’s infamous distribution of his new film Red State (opening this month in Australia/NZ) to the latest Flicks-sponsored “Make My Movie” Competition currently running.

It’s a pretty murky mire, but let’s dip our toes and see what comes up from the depths to say ‘hi’ as we explore the (very basic mind you) ins-and-outs of film distribution.

To refer to the work of writers Terry Pratchett, Jack Cohen and Ian Stewart: the thing that makes humans completely different to all other species that inhabit this planet is stories. In short…we are the only creatures that tell stories for fun. And like most things that happen in the collective human perception of space and time that we refer to as ‘our lives’, we experience stories as singular ‘events’.

Cast yourself back to the days of primitive man, when life and death were separated by discovery of a particularly dim-witted and tasty mammoth or a rather hungry and unfortunately agile saber-tooth tiger and you’ll find that entertainment was a fairly limited past-time. That is to say it didn’t necessarily bombard us with constant distraction in the way that it does today. However entertainment did exist and it came in the form of things like drawing pictures of the bison you killed to show off to those obnoxious guys who lived in the cave next door, dropping fat drum’n’bass bombs on your skin-and-gourd set and, of course, having a magical story-time session with your local shaman or story-keeper.

And when the story-keeper gathered you all around the campfire, after dinner and perhaps romantically under the glittering stars of the universe beyond, the telling of stories and weaving of tales was AN EVENT. The village campfire was the proto-theater (or cinema / television / media device) and the storyteller was film director, producer, distributor and exhibitor in one. BUT he still needed all of you to sit your ass down for an hour or so in one place so he could tell his story because, as humans, we engage with the telling of stories as singular events that require our full and undivided attention.

Flash-forward now 100,000 years to the modern 21st Century and you’ll find that my (rather simplistic I admit) model still does apply in the modern world. We humans, who have now multiplied and evolved and found whole new media streams to distract us from quality mammoth-hunting time, are still engaging with stories (whether performed, prerecorded or interactive) which now compete for our attention on a planetary scale. And to experience these stories across the ‘global village’ we gather around, either by ourselves or with our friends and family, the proverbial modern day campfires that is the cinema, television or media device screen to have our imaginations stirred and our emotions manipulated and invigorated. But because the ‘campfires’ now relay the story in an indirect way, no single storyteller can call the whole world to its attention in one breath…but because the whole world is now attentive for new stories, it is vastly more economical for that storyteller to address as many of them in one breath as possible. To solve this seeming Catch-22 situation birthed by the invention of such modern technologies as the printing press, the radio, the camera and the Internet, it became apparent that the storyteller had to finally separate him or herself from the duty of distributing and exhibiting their work and focus solely on creating the stories so that others – who had become specialized experts in that field – could then take it to the world.

Or to put it another way: because the storyteller’s campfire is now the size of the planet and everyone around this campfire wants new stories all the time, someone had to come along and make it their job to get the stories across the planet-sized campfire quickly and efficiently and find more storytellers and stories to keep the demand met. Thus was born: THE DISTRIBUTOR.

Of course this is being highly simplistic: the long and noble art of distribution shit-that-people-want-and-need has been around since the days when humans had names like Thag and Kronk, but of course in those days the only thing that needed distribution was stuff to eat, stuff to build houses out of and stuff to stick into other people named Thag or Kronk. Distribution and ‘transportation’ were practically synonymous. With the advent of the wheel and the boat, people made it their business to lug crap around from one place to another in the hopes of getting said crap sold to people who desperately needed it and didn’t have any of it lying around for free. In that essence, you could say that film distribution isn’t anything new; it’s just that instead of hauling spices across the Indian Ocean or cabbages across Medieval Europe…they’re hauling movies to the people of the world.

Ignoring all other media formats (this IS a film blog after all), film distribution is – without a doubt – where the money circulates. Without distribution, filmmakers don’t get your hard-earned spendola and without distribution you don’t get to blow your cash on crap that you probably were better off not having seen. The world of film distribution is, to some degree, a world of power politics, pressure and cutthroat savagery that would make any sea-faring buccaneer proud. If distributors did not have the money and resources, you would not have been able to see the latest movies from Hollywood and beyond and if distributors didn’t have power and influence, your film that you toiled and sweated into creation will never be seen by anyone except your (no doubt) long-suffering parents.

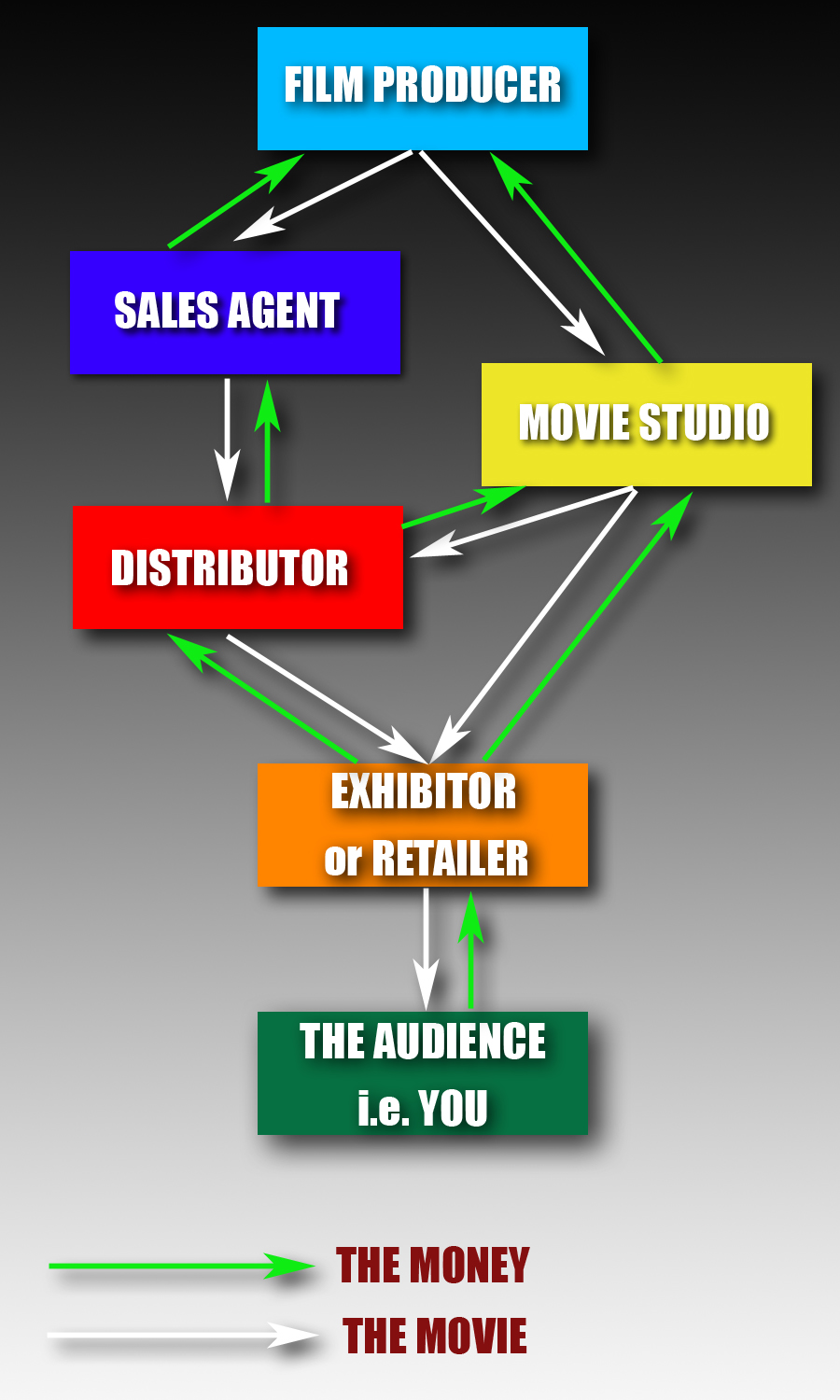

How does it all work? Here’s something I prepared a little earlier:

A couple of important points:

* The above diagram is an ABSOLUTELY MINIMALISTIC and BASIC representation of the film distribution chain. If I were to attempt to draw a flow-chart of a realistic model then it’d look more like advanced dance-steps for this year’s competition-level Cha-Cha.

* The above diagram is a TRADITIONAL model of film distribution and one that is changing to some degree as media conglomerates try to catch up with the modern shape of the Digital Age.

And here’s how it goes:

1) The ‘film producer’ is, for argument’s sake, the modern equivalent of our ancient campfire shaman or story-teller. He’s just finished a movie and now needs to get it out there into the market to make him some money.

2) The producer gives the movie to either the studio that financed it OR to a ‘sales agent‘ who is, basically, like a real-estate agent for films. The sales agent will have the job of selling the film to prospective ‘distributors‘ looking for awesome movies to take out into the market. This transaction occurs in many places: private meetings and deals, film festivals, annual film markets (like the American Film Market) and more.

3) Once the distributor has the bought the rights to on-sell the film, he will then take it to ‘exhibitors‘ (individual movie theaters or major cinema chains) to see if they will screen it. If the movie isn’t very popular with the theaters, the distributor might offer a ‘package deal’ where a cinema will get a set of films they really want to screen for a cheaper price, but only if they also promise to screen a few films that aren’t selling very well. Anyways, eventually the film finds itself at a theater and you go to see it.

4) Once you’ve paid for your ticket to watch the movie, the cost of that ticket is then broken up and the money works it’s way back up the film-chain. The theater pockets a percentage of your money, then the distributor for his services, then the sales agent and, eventually, the filmmakers.

5) If the movie was financed and owned by a ‘major studio‘, then the studio will often play the role of distributor as they have private deals with many movie-theater chains. Like distributors, a studio may extort a theater to buy less-popular films on their slate in package deals in order to have the privilege of screening mega-blockbusters that the theater really wants. If for any reason a studio doesn’t have a per-existing deal with a city, country or region’s cinemas then they’ll hire distributors who know that local market to sell their films for them. And, of course, sometimes a studio will distribute films which they didn’t make or finance at all (examples of this include famous independent blockbusters like District 9, Paranormal Activity or the Star Wars prequels).

6) Lastly, you can replace exhibitor with ‘retailer’ which can be your local video store, DVD shop or an online service like iTunes or NetFlix.

Of course…there is a problem with this model. And I’m sure you can guess what it is.

'Arrrr'

The short version: piracy.

The long version: modern technology is (supposedly) making it easier for filmmakers and the audience to infringe on the economic model that distributors and exhibitors live off.

Prior to the access of high-speed, semi-decent quality video and audio via the Internet (and don’t fool yourself kids, the ability to get actual high quality video and audio for movies and TV shows is still out of your reach), distributors and exhibitors were the gatekeepers of media content. They guarded all the doors, they held all the keys and the audience (you and me) obeyed their instructions on how, where and when we would be able to watch our favourite show or see the latest film. But with the rise of online video and file-sharing, that power is slowly being taken away from them. The consumer is now slowly taking control of when, how and where they’ll watch their media content: no longer do they have to wait for their local TV station to get the latest episode of Dr Who or their local multiplex to screen the next Harry Potter film. If your local distributor/exhibitor doesn’t provide for your demand, then simply reach out into the net and take it for yourself.

Naturally, this is a scary scenario for a lot of people.

There are three-fold events occurring that is threatening the old distribution model (as shown in the flowchart above): the first is that in the 21st Century, the digital-cavemen around the campfire can only have their hunger satiated by instant gratification. The second is that this demand for instant gratification is threatening the infrastructure, relationships and power-hold distributors and exhibitors once had and grew fat and happy on. The third is that the shamans and story-tellers of the world are now feeling that they’re being deliberately distanced by their distributors and exhibitors from the campfire and some are taking matters into their own hands.

If this were commentary on the spice trade of the 13th Century, the merchant ships carrying goods from Asia to Europe would be greeted with the sight of consumers zipping past their sailboats on Jolly-Roger-flying high-speed hovercraft, laden with their own loot they bought from the manufacturer, while taunting at the merchant vessels for being too slow and too expensive. Literally, distributors seeing consumers and suppliers engaging in business without them facilitating the transaction or making their percentage. And, if you think about it, a thousand years of distribution infrastructure and dependency has made these people the most powerful organizations in the world. Record labels are distributors. Movie studios are distributors. And of course they’ll fight tooth and nail to protect their investments. They’ll sink your hovercraft long before they’ll buy a fleet of their own and find a way to get your spices to you faster than you could on your own. The ethics are superficial, it’s about money and everyone is trying to save as much of it as they can. In response to these seemingly violent shifts and changes in the film distribution world, there’s been response from the shamans and storytellers (i.e. filmmakers) who suggest that we’re about to enter a brave new world of ‘self-distribution’. This buzzword has been the rally-cry for armies of frustrated filmmaker for generations who lament at the fact that audiences won’t see their stuff because the people who can distribute it think it’s unsellable or potentially too hard to try. Self-distribution is a prophecized holy grail that promises to level the playing field, give penniless artists a voice and install a 24 hour ice-skating rink into the seventh level of Hell.

In short, a paradigm shift.

This, for my personal opinion, is a mixed-bag of genuine advancement and inaccurate vapor-hype. The advent of nearly-free content (because nothing is truly free: the Internet costs you money, has a carbon footprint and obeys the first and second Laws of Thermodynamics) produced by people who merely want their Warholian 15-minutes Of Fame has opened up the possibilities of easy-online-distribution of media content. However, the problem with this is that it’s still distribution and distribution still takes time, energy and incurs hidden costs which the filmmaker/shaman has to take into account and will interfere with their dedicated career of being story-tellers. Like a Renaissance mummer troupe, filmmakers who self-distribute now must hitch up their virtual (or real-world) wagons and take their product around the global campfire themselves, generating their own advertising, finding venue after venue to perform and exhibit their work and ensure that the exercise doesn’t economically collapse their business in the process. The ability to launch media content simultaneously in theaters all across the world (as often happens with mega-blockbusters like Harry Potter or Transformers) requires a technological and expertise infrastructure that only the financial resources of an established distributor can afford. Young, penniless, Internet-pirate shamans who self-distribute do not enjoy that sort of exposure and must find other means to generate demand for their product which can easily be shouted down by $300 million worth of marketing.

Examples of self and alternate-distribution models are already here for film:

Outspoken, cult and geek-filmmaker Kevin Smith (aka Silent Bob) caused a bit of a ruckus at the 2010 Sundance Film Festival when he announced that he would be self-distributing his latest film – a religious horror thriller Red State – in a publicity-stunt event where he suckered many powerful distributors into a fake auction for the rights to his film (perhaps to rub their faces in it). Smith announced that he would be testing a business model of a filmmaker-distribution company (entitled Smodcast Pictures) and taking his film directly to Direct-To-DVD/Video-On-Demand retailers after a very brief ‘roadshow’ of screenings around the USA. Smith felt that it would take a celebrity with media power to prove such a model could work before unknown filmmakers could attempt it for themselves – in short cutting out distributors altogether and giving many filmmakers the chance to be accepted or turned away by retailers and exhibitors directly rather than have their work be screened by distributors and be cut out of the financial back-end of their own movies. Smith can’t be faulted for his pragmatism which is rather in-line with his controversially outspoken stance on the film industry in general. And true if Smith’s model proves successful and then some unknown nobody filmmaker somehow manages to replicate his success (the odds of this is rather difficult to predict admittedly) then a potential floodgate could open up for filmmakers to self-distribute their films.

Smith himself cites he was inspired by Mel Gibson’s self-distribution model for The Passion Of The Christ which rejected by all major studios and so Gibson released the film with his own money and focused his marketing mostly at churches who were encouraged to market the film among their own congregation. This targeted micro-marketing and micro-distribution is another key focus point for the ‘new digital age’ of filmmaking where under-resourced filmmakers don’t use blanket advertising to help their movie find an audience, but instead systematically hunt down their ‘ideal audience members’ and focus on them specifically. A recent example of was in the critically-lauded film independent drama Winter’s Bone which started to build online hype about the power of their product by first systematically showing the film to communities in the Ozark Mountains where the film was shot and takes place.

In this manner, movies are becoming more ‘personal’ in their approach to the audience and, thus, shamans are reaching across the campfire to shake their audience by the hand. Even movie studios are getting into the online-and-personal-game: Paramount Vantage’s distribution model for their mega-hit Paranormal Activity was to run trailers online and in movie theaters asking for audience’s to ‘request’ the film to be screened in their city on the movie’s website. If 100 people from any town or city successfully requested the film, the movie would play there. And if 1 million people requested the film then Paramount would open the movie nationwide…and they did. Why? Because if you personally went to the film’s website and requested to see the movie then it is very likely that you would make the effort to go and see it. And, because we don’t like to sit at the campfire by ourselves, most of us would bring a friend…or five. And that is why Paranormal Activity was one of the biggest hits of the year despite the fact that it was an amateur movie shot by a first-time filmmaker, but distributed by a studio who had a genius plan up their sleeves.

Another way films are becoming more personalized is the advent of ‘crowd-funding’ – i.e. asking your audience to give you money to make the movie they want to see. Crowd-funding is something of a sensation that a lot of people are trying to cash in on (excuse the pun), but like anything the execution only matches up with the quality of the idea being presented. Filmmakers are trying to make specialty products for highly discerning customers so you have to have something decent to offer to convince someone to part with their money. Luckily, there are quite a few people who have some pretty awesome shit to sell.

Iron Sky is a Finnish crowd-funded feature film project which promises a tongue-in-cheek science fiction epic where the Nazis (who fled to a secret base on the moon in 1945) return to wreak their vengeance on mankind with a fleet of flying saucers. Currently in post-production, the film has gained a legendary status on what the power of crowd-funding can achieve with the right project. I mean c’mon, who wouldn’t pay money to see a movie about MOON NAZIS? Crowd-funding has also allowed projects of a very specific and catered taste, that studios and commercial filmmakers wouldn’t be interested for lack of financial returns, to be made. An example is this beautiful (and now fully funded) project by VFX artist Christopher Salmon who wanted to adapt celebrated writer Neil Gaiman’s haunting short story The Price into an animated short film:

So the digital age and the Internet has changed the distribution game. The effects of this has already (with much screaming and protesting from record labels) taken effect in the music industry, revamped and reshaped the gaming industry and is now taking its hold on the world of television and feature film. But will self-distribution and the perceived “power” of the Internet give filmmakers that elusive break they’ve craved for so long?

Well…if they want to direct the next Batman movie then answer is a flat out no. You’re not going to be ‘discovered’ and ushered to the head of the queue. The world doesn’t work that way. And if there is some suggestion that distributors will be gone for good then that’s equally ludicrous – self-distributing filmmakers will always diverge into people who are good at making films and people who are good at distributing them and the latter of those people ARE, by definition, distributors. The methodologies are changing and a lot of ‘old-school’ people who are unable to keep up with the new world will have to throw in the towel. And of course if your film is total bollocks then no amount of self-distribution pep-talking is going to make your audience want to watch your monstrous creation (young filmmakers please take note here: if distributors turned up their noses at your film then don’t be surprised if a paying audience does the same!)

But amidst all this chaos and confusion and changing ethos, just like in the old days, genuinely good filmmakers and genuinely savvy digital age distributor/exhibitor (and/or any other hybrid) organizations will always find a way to turn an honest buck and transform the campfire into a place of wonderment and magic regardless.

Before I go, there’s one more thing I want to address and this one is very close to home! As some of you may be aware, Flicks has teamed up with Ant Timpson, the New Zealand Herald online, the New Zealand Film Commission and NZOnAir to create THE MAKE MY MOVIE PROJECT. As another example of the divergence of online marketing, distribution and crowd-sourcing, the project sets out to award $100,000NZD to the best proposed feature film project as voted by a panel of industry professionals AND the public who get to give their own opinion on what they would like to see. Harkening back to the days of William Castle and Roger Corman where films would be made and sold on the strength of a poster alone, Make My Movie asks filmmakers to pitch their projects via a teasing synopsis and a self-made movie poster in order to tantalize the judges and the public.

Even purely as an exercise in taking the nation’s temperature in terms of what young filmmakers want to make and want the public want to see, there are some fascinating entries and fun-looking projects that speak for all tastes. Projects like This Papier Mache Boulder Is Really Actually Heavy, 90 Minutes and The Book Of Bees really capture the imagination on what is possible with such a tight budget. And of course when there’s no money, there’s always room for gore and scares with horror projects like Never Be Enough, The Copycats and Infection. And there’s room still for romance, drama and even war films. Granted it’s not all good perfect as there are a slightly worrying number of entries that couldn’t be possibly shot for a million dollars, let alone $100,000 and there are a few entries which can be hard to decipher given the writing style of the synopsis and posters.

And of course, because I have to use my platform for shameless self-promotion, I highly endorse you check out my submission Number 8 Wire – a survival thriller with a difference and a fair bit of Kiwi ingenuity on a lethal level!

To vote for your favourite projects, simply click one (or ALL!) of the Facebook, Twitter and Google Plus icons on the right-hand-side of each film’s page. You can, of course, vote for as many films as you want, there’s no sign-up and you certainly won’t get any spam! The top 12 films will then go into a second voting round through the month of November and the winning film will then be picked, produced and released sometime in April next year! And this is purely possibly only by power of the Internet, social networking and the new dynamics introduced into the world of classic film production and distribution.

So…what will the future hold for us?

It’s too early to say as the money-people are still struggling to come to grips with the new tools and pitfalls before them. The access to films will no doubt increase both in speed, immediacy and variety in the near future and already we’re seeing flow-on effects in our movie houses where the focus is moving away from content delivery to comfort delivery, turning our traditional campfire into a luxurious experience that rivals our own living rooms and laptops. The threat of Hollywood’s marketing machine may diminish as films from lesser-financed markets became easily available online (or perhaps they won’t?) and the tide of amateur film and home-made content will be stemmed as audiences grow to reward high quality content and tune out the lesser-made cries for attention. Ultimately there’s no real vision yet and while this is seen to be part of the problem, there is an exciting electricity in the air as the future rolls towards us one day at a time.

But if history teaches us anything, we know that these changes will not make the world nor the market of film a fairer place…merely that it will shake things up enough for a very different group of story-tellers to have their turn in the sun. For my part, I would advise everyone to stay away from the utopian hype and snake-oil promises that people are making about digital distribution simply because the technology is changing too fast to form any sort of accurate picture about the future. But, at the same time, there is opportunity to bask in the potential of the glorious changes it will bring and the imminent future peaking over the horizon that will ensure that, no matter what happens, people will be working their arses off to get you your movie-fix in record time.

Thanks for reading.

(and don’t forget to vote!)