In season 3, The Great is still an orgy of satire, stupidity, and soul

Unlike many of its period contemporaries, The Great veers away from history for the purposes of wit and imagination.

We’re all drowning in content—so it’s time to highlight the best. In her column, published every Friday, critic Clarisse Loughrey recommends a new show to watch. This week: gleefully ahistorical comedy The Great, finally available to watch in the UK. Huzzah!

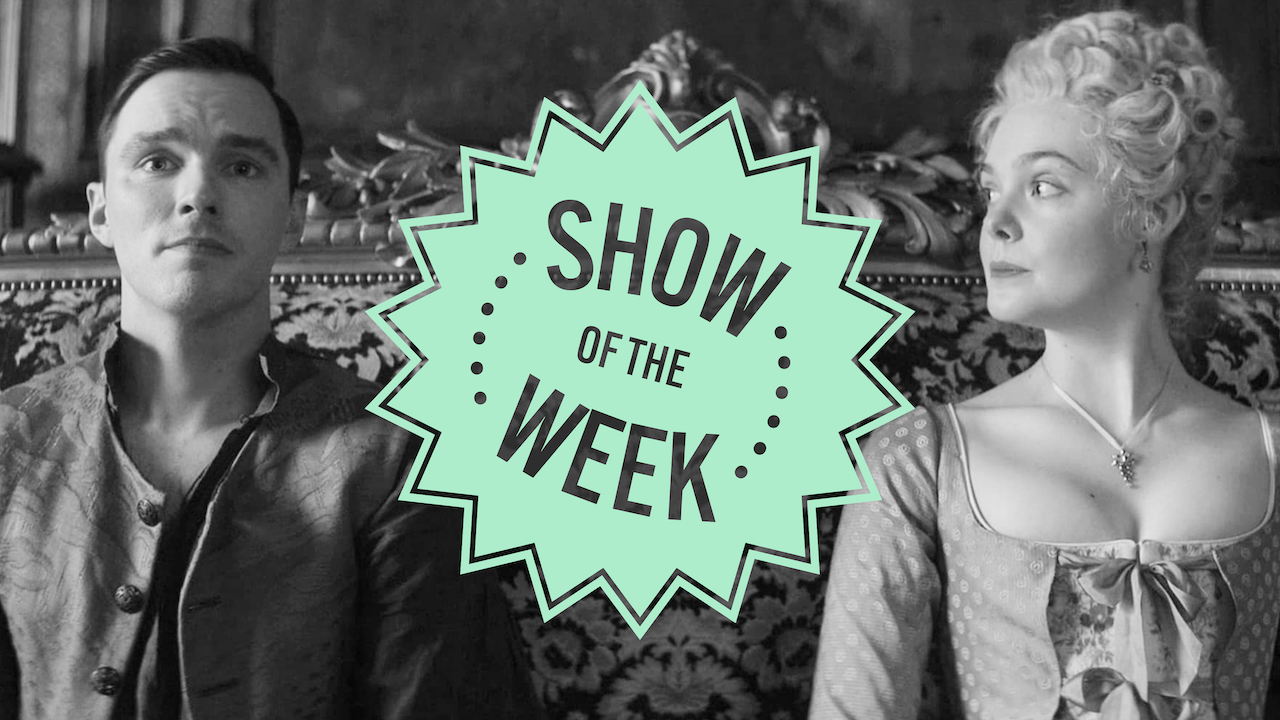

“This is why we’re perfect together,” Peter (Nicholas Hoult) coos to his royal wife, Catherine (Elle Fanning). Each has found a knife under the other’s pillow. With good reason—she has already stabbed him five times, only to discover it was actually his overly-toothed lookalike, Pugachev (also Hoult). He, previously, had bedded and then unintentionally dropped her mother (Gillian Anderson) out of a third-story window.

He is the deposed Russian emperor, occupied now with hunts, orgies, and being unquestioningly adored by all. She is the one who succeeded him, a German idealist married into a nation she’s now determined to reform.

The real Catherine allowed (or ordered) Peter to die while under house arrest shortly after her ascension to the throne. At the start of season three of Tony McNamara’s gloriously ahistorical, yet faithfully spirited invocation of 18th-century Russia, Peter has not only been allowed to live—he’s been allowed to love.

The royal couple have agreed upon a fragile, and psychologically volatile, truce. They are surrounded entirely by courtiers—among them Catherine’s adviser Orlo (Sacha Dhawan), Peter’s aunt Elizabeth (Belinda Bromilow), religious patriarch Archie (Adam Godley), and Catherine’s best friend Marial (Phoebe Fox)—who remain baffled as to how such inexplicable, personal desires could determine the country’s future.

It’s all so deliciously dramatic. So, really, who gives a fig whether any of this self-proclaimed, “occasionally true story” actually happened? Unlike many of its period contemporaries, The Great veers away from history for the purposes of wit and imagination, and not because its creators have convinced themselves that their source material desperately needs to be improved upon.

Bridgerton and its ilk have determined that this era of labyrinthine undergarments and aristocratic manners is dreadfully dull and in need of “sexing up” in order to appeal to modern tastes. And yet, Regency partygoers were known to be fond of games that necessitated they sit on other people’s husband’s laps and steal kisses on the sly. When a TV show aggressively markets itself as a “modern spin” on the past, you can almost guarantee that it’s relatively chaste compared to what really went on behind portico doors.

The Great, refreshingly, presents sex largely as it would have been—as a savvy combination of hedonistic indulgence and political manipulation. Catherine (the real one) became famous for her affairs with younger men. This, in itself, wasn’t at all unusual. Her adversaries instead attacked her with numerous rumours of sexual deviances (one, involving amorous relations with a horse, has become a recurring gag on the show).

It’s quite easy, then, to forgive Peter’s undeadness in The Great when the show’s historical inaccuracies still reflect the spirit of the age, as if they flowed from the pen of Voltaire himself (Dustin Demri-Burns, still languishing around the palace in season three and saying terribly French things). Catherine’s reluctant declaration that every village shall have a monkey feels precisely like the sort of legend that would spread about her. At the same time, the American and British ambassadors’s spat over the removal of “u” from “colour” is a pitch-perfect bit of revolutionary humour.

And McNamara, who’s written (or co-written) each of season three’s 10 episodes, with five made available to critics, has allowed these real figures to become representatives of the chaotic battle between desire and duty. Progress is almost always hampered by the selfishness of the elite, even when they attempt to conceal it behind specious ideology. It’s met equally with distrust by a people so abused by their rulers that they can longer tell good intentions from bad.

But The Great is deeply humane, too, as Peter’s caviar-addled heart softens in the presence of his infant son, while Catherine’s hardens with every illogical barrier she faces. The Great, in short, is an orgy of satire, stupidity, and soul. Huzzah!