The violence and emotional gravitas of Coming Home in the Dark

Director James Ashcroft and actor Erik Thomson join Steve Newall for a chat about their impactful film Coming Home in the Dark.

A family trip through the New Zealand wilderness turns into a nightmare when they’re suddenly confronted by a pair of drifters in a superb new local thriller. Upon seeing (what’s remarkably) Ashcroft’s debut, it’s quickly apparent why Coming Home in the Dark has wowed audiences since its world premiere, and justifies Hollywood’s keen interest in Ashcroft as a director (one of his upcoming projects will see Ashcroft adapt Max Brooks’ “Bigfoot horror thriller” Devolution for Legendary Entertainment).

As you’ll find out for yourself when you see the film, there’s plenty to unpack—from moments which physically rock the viewer to a cumulative impact that left everyone in my screening silent and shaken as the credits roll. In the interview excerpts below, James Ashcroft and actor Erik Thomson discuss key topics from our conversation.

THIS INTERVIEW HAS BEEN EDITED FOR LENGTH AND CLARITY

On adapting, and expanding, Owen Marshall’s short story

JAMES ASHCROFT: The short story was such a great initiation. I mean, it was something that I definitely knew I wanted to do, but it wasn’t enough. It was the starting point. I set it aside for a couple of years, actually, until I found something that we could get underneath the actual story—sort of use the short story to speak to and address some of those issues.

That happened quite organically. [Co-writer] Eli Kent and I, we explored a couple of different themes and scenarios to begin with, until we sort of gave ourselves permission to go, “What is speaking directly in that short story?” That then allowed us to find that element of the boys’ homes and that long shadow of institutionalisation. That was always something that I was interested in. I mean, I had family members who have gone through that system before. I produced a documentary about the Epuni Boys Home. So I was interested in that world, but it really came from meeting former residents of the home and former staff. Some of those residents are people who have gone onto be indoctrinated into crime, and some of those men who I interviewed who worked there, some of them have had a very, very long sheet of accusations made against them.

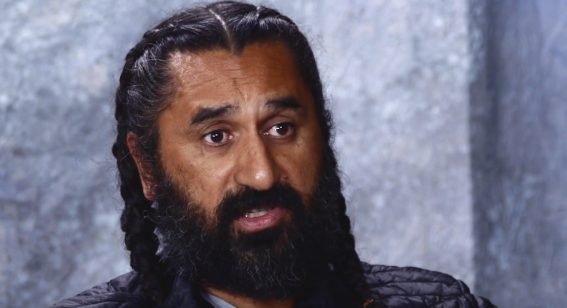

Did the cast know how difficult a shoot this would be?

ERIK THOMSON: I had an inkling. I certainly had an inkling several months out. Several days out, I had far more than an inkling. Yeah, I kind of freaked out because I knew it was going to be really big. A lot of fear kicked in just prior to the shoot, and that was part of the process, and it was kind of a necessary doorway to walk through, in retrospect, to get there. Because, yeah, it was quite emotionally demanding. Demanding physically and emotionally and psychologically.

We had a meeting with the cast and crew at the beginning, and James said, “I am going to ask more than 100% of everyone.” And everyone kind of stepped into that space knowing that we weren’t going to be on social media just hanging out and then just phoning it in. We were all going to get asked to go to a place that we hadn’t been in order to make this film, and we were all willing to do that. It was dark. It was winter. And I was getting dragged out of cars. It was actually happening. We just had to jump in feet first, really. But yeah, the environment helped.

You know that it’s fantasy, but your body doesn’t. Your adrenal system doesn’t know. Your adrenal system kicks in. You’re drawing from your emotions, and after a while, it does have an effect. And I think, from an emotional perspective, it’s probably the hardest job I’ve ever done. On quite a lot of levels, actually, it was probably the hardest job I’ve ever done. I was happy to be in that situation, but it was a demanding production, and I think you can probably see that in the finished product.

Erik Thomson

On the cast as an ensemble

JAMES ASHCROFT: I can’t imagine anyone else other than who’s in the cast. Those roles are all cemented. I loved the look of all four of them together because it’s almost like, well, an Englishman, an Irishman, and a Māori man walk into a bar [laughs]… other than being cast because they’re all the best at what they do.

To me, it wasn’t necessarily intentional, but it’s a great representation—Māori-Pacific, Pākehā, English-Scots. It’s a great ensemble piece, but everyone got the role because they were the best actors. Where it really worked out well was that it became a great ensemble of collective energies, and it was just very pleasing to watch. I loved watching them. It was a proper ensemble film, and it was nice to see, again, last night, that it’s hard to say it’s any one character’s film. I think you do walk away going, “It’s those four characters.”

ERIK THOMSON: Daniel Gillies had done so much work on his character [Mandrake]. It was so different from him, and he really worked and worked and worked, and I was kind of feeling like, “Shit, have I done too much…” or, “I haven’t done anything…” I mean, all I have to do is kind of react honestly between action and cut in the given situation. I couldn’t really prepare for the role. But Daniel really characterised it: his teeth, and the look, and really stepping away from himself as the protagonist, really. So I was super impressed with where he went and how he took that character.

Matthias [Luafutu] has a back story, personal back story, which loops into some of the stuff that we’re dealing with. He embodied, in many ways, the world that we were inhabiting. And his presence in that car, sitting beside him, there’s a weight, a huge amount of gravitas that he employs, and that was amazing. And Miriama [McDowell], her ability to just jump, emotionally… Everyone was just so committed, and that inspired me.

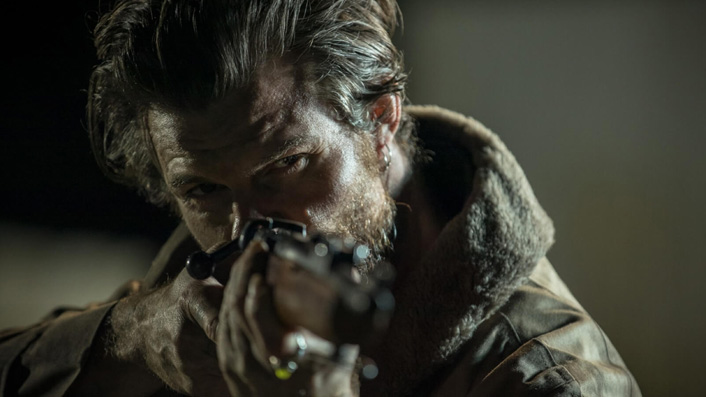

What’s driving Daniel Gillies’ character Mandrake

JAMES ASHCROFT: My feeling and Eli’s feeling was always, Mandrake especially, when we meet him and Tubs, it’s like they probably haven’t got long to go in this world, just in terms of how life has unravelled for them. His callousness and disdain for everything is about being seen, about making a mark, about recompensing in his warped view. He does make his actions very unforgivable, which they should be. That’s what we’re sort of striving for, is to sort of have someone do the most reprehensible things imaginable, and still start to question and get into a conversation about what those motivations are. It should be difficult to reconcile because people are difficult to reconcile.

Daniel Gillies

On one specific, shocking act of violence (you’ll know it when you see it)

JAMES ASHCROFT: We had resolved to move forward with that moment, but that was the one moment that funders and market partners always questioned first, like, “Well, can we not..?” But again, the intention of it, and Owen’s story, is very pure and clear and affects the whole. It’s the catalyst for the entire film in many ways, and thematically, too. So we felt very clear about that. But yes, it was a gratifying moment to see the audience react and to hear gasps.

ERIK THOMSON: When I read it, I just went back and forth over that bit of the script going, “Fuck, did they just do that? Did they just do that?” And I knew that the courage and the audacity it clearly set the intentions of the filmmakers at that point. It was going to be unapologetic, which was very exciting and scary.

I mean, how do you react? Thinking as an actor, how would you react if that kind of thing happened? I remember really knowing that there would be just an overwhelming disbelief, and I can’t even put into words what the correct response would be—that the primal would take over. And being open to that primal and allowing that to kind of come through, from an acting point of view, was scary and kind of liberating at the same time because how do you act it? You had to kind of live it, just really, really rip that bit open.

JAMES ASHCROFT: Technically, there’s very little violence that’s shown directly on the screen, and we definitely don’t glorify it, but I think that’s because there’s a banality to it. It’s cold. It’s indifferent. It’s economic. And I think, that way, the violence is more in your perception as a viewer, and that makes it much more visceral and confronting rather than a semi-pornographic approach to exploitation of violence.

NZ’s flavour of horror and the influence of our past

JAMES ASHCROFT: I love horror, and I love thrillers. I love psychological horrors, psychological thrillers. Because genre approaches certain subjects and things that are a little tricky to address in just a purely dramatic way, and you can unpack them in a way that’s going to open people’s mouths with screams and gasps to stick something serious down their throats to consider. Italy has Giallo as its brand of horror to do with repression and corruption in politics and religion. And I often think of what’s New Zealand’s flavour of horror, and I think it’s very much tied into that banal, punitive nature that we have in our society as an advent of colonisation because, there, it’s something that I find really fascinating to unpack.

ERIK THOMSON: There was just something very much about taking the character of Hoaggie, the white, middle-class man, and turning him back, and just making him face that past as a metaphor of actually looking back and looking at this kind of different era. Where things were dealt with a certain way, where the government owned everything, or the state owned everything. A huge amount of sins were done. And we all knew. We all knew about the boys’ homes. Like [Erik’s character] Hoaggie says, people believed that they deserved it.

Miriama McDowell

Establishing the visual style of the film

JAMES ASHCROFT: I credit Matt Henley, our cinematographer, with that. Matt and I have been working together over a number of years—this was his first feature as well. He had turned down a couple of features to focus on this and debut with this, so I’m glad his work’s being really acknowledged and recognised. Matt and I, we did eight short films together as a warm-up towards this.

We both have a very sort of similar taste. We used two primary references for this, which was to do with the duality in the film, which is light and dark. So it was the paintings of Grahame Sydney. And the paintings of Daniel Unverricht, who uses all those things and does these nocturnal landscapes.

Where’s that space between night and day? That’s what we were looking for, and every moment, whether it’s humorous, whether it’s dramatic, how can we always be getting that sense of night and day being at play at either end of the frame. What was great about working with Matt is that we had that shorthand. How do we look for the beauty in every image, no matter how grotesque?

I have been in the most beautiful places in New Zealand. On the land, the sun shining high. There’s no wind. It’s beautiful. And every now and then, I’ll get a shudder of feeling that sense of space, isolation, claustrophobia, and it doesn’t matter what happens. The land’s indifferent in its beauty and its ugliness to all that goes on on it. But it does retain, like burned toast, it retains the smell of it.

Working towards another Owen Marshall adaptation

JAMES ASHCROFT: Look, I like Owen’s writing overall. I met him the morning after he had won the Prime Minister’s Literary Achievement prize to speak to him about Coming Home in the Dark and The Rule of Jenny Penn specifically, thinking, “He’s probably a bit hungover. He might be a soft touch.” And he just said, “Okay—well, that’s great. I think that’d be good if you go and make those two films. They’re the two darkest stories I’ve ever written, so I guess that says a lot about you.”

I mean, my sense, at the least, I’ll always lean to the darker side of the material, like genre, because you can pack things in it in an interesting way. But ultimately, as with The Rule of Jenny Penn, it’s the tone, the characters, and the insight into a moment or an environment that is so idiosyncratic and opens your eyes up to something that you thought you knew but you never really looked closer and then contemplated the fragility of life that is always there. There’s no surety there.