Interview: Ben Mendelsohn Talks the Emotionally Intense ‘Una’

Una sees Ben Mendelsohn star alongside Rooney Mara as the latest in a spate of morally dubious characters he’s played in recent years. Steve Newall sat down with Mendelsohn in Australia while he was there to present Una, and take part in a hilarious, illuminating Q&A in front of a packed house, at the Sydney Film Festival.

The film, adapted from lauded play Blackbird, follows Mara’s character as she tracks down, and confronts, the man who had a sexual relationship with her as a young teen. Una plays at the NZ International Film Festival.

‘Una’ is based on the play ‘Blackbird’, which I haven’t seen, but am aware of its reputation. Had you seen productions of it before the starting on this film?

No, my first contact was reading the script, so that was the first time I’d had anything to do with it. And I got very caught up in it, so it was a very quick yes to doing it for me. Because I knew Rooney [Mara] was in and I knew Beno [Benedict Andrews] was directing it. But yeah, I got very caught up in the drama of reading it and I loved it.

We see your character in two distinct periods of time as the set up to what transpires in the third act of the film. Was there one of those aspects that you gravitated to the most strongly?

No, not really. No. Well, I mean, look, it’s the main body that’s in the play that I think is that’s the meat of the piece and that’s probably, if I was going to say anything, it would be what’s classically defined as the Blackbird-ness of it. The other bits are Beno’s, sort of, cinematic extension of them.

Is it a different process when you’re bringing something that’s got such a strong theatrical component to the screen?

Yeah. I think for Benedict it probably is, more than necessarily it is for us as actors. I mean, you don’t often get those kind of extended exchanges of dialogue in a typical movie. But I think Beno’s concern was we’re making a film here, not shooting a stage, not shooting a play, and so that was a concern, I think, a lot more for him, and the technical side of things, than it was for us. Although, having said that, it’s not typical to be doing a series of long exchanges or extended exchanges.

How do you go about preparing for depicting a character at such a different stages of their life as we’re seeing?

I don’t know.

Like, from the ebullient part where he’s being swept up in what’s happening in the past, to the present version?

I think most of these things are created in context. So I think a lot of that work gets done for an audience by the way he looks and the fact that he’s with the young Una, the period afterwards. And I think, in the same way as people might behave differently if you go out with your girlfriend’s family, to if you go out with guys that you’ve known since you were 15, it’s the same sort of a vibe that happens, I think, when you’re portraying someone in different periods or circumstances of their life. You just kind of have a sense that you’re going to know what to do or try, something that feels more spot on than not.

It’s really important for the film to have sympathetic elements to your character because otherwise it would mean purely being set up as a villain for the piece. Is it difficult to go into a character that’s got such trauma or has done fairly questionable acts and actually build up a sympathetic element to them?

No, no. No. Because I’m not confused, the way I look at the person is not the way that that character is presenting themselves and talking about themselves. So no, there’s no problem for me with it whatsoever. I don’t look at it as my judgement, commentary, opinion, or anything on that. I approach it more as someone trying to make the writing come to life and sort of sing.

So I never, ever, ever, get confused between what a writer is doing in a piece as to what I think about it. Never. Never, ever, ever.

And I see them as very distinct areas of concern. And I guess the thing, if anything, that surprises me is that it would exist as a confusion in adult viewers, not necessarily in young people. I get how that stuff can be sort of automatic. But in a sort of a mature sort of educated palette, that’s where I get surprised. And it does happen a lot, that people confuse the two. But that, to me, that’s the wacky bit.

Right, yeah. It’s the power of the moving image even on a educated or mature mind.

Yeah, that’s it. Or the inability, I suppose, to be reflective about it if they were considering that question. Yeah.

That’s probably not a million miles away from another question I was thinking about. In ‘Una’, basically, the vast bulk of your interaction with Mara throughout is in the context of very heavy dialogue and very heavily thematic work. If you’re turning up to work on set every day, are there moments of levity within that?

Oh, absolutely. I mean, we spend a lot of time laughing, and just hanging out, and just talking, having perfectly pleasant small talk and whatnot in amongst all that. You sort of need to save your ammunition, as it were, for what you’re going to do. And outside of that, you want to take the pressure out and off.

I think it’s a real waste of energy and emotional intensity to sort of try and artificially sustain that kind of stuff in between times. I mean, I’m sure there are people that might attempt that but I think it’s ill-advised and I think it’s actually counterproductive. I think it’s a misreading of what it is you’re doing there.

I guess to some extent, because we’re following your character through a fairly narrow period of time, that you’re working with one portion of your range as an actor, right? And so then the nuances become very, very important. Was that one of the things that interested you, those small variations?

Yeah. But that’s sort of something that I think you get to do when you go to work. If you get more than one or two goes at something then, more or less, hopefully you’re starting to trying to perfect the pitch and tone, or you’re trying different things out. So that’s always one of the joys about actually getting to do scenes, and again and again, is hopefully you try different kind of bits and pieces and approaches.

I think I just missed you in Twizel. I went down to ‘Slow West’ for a few days when that was shooting in New Zealand. It seemed like the approach on that film wasn’t really so much about trying things as director John Maclean knowing exactly what he wanted just going, “It’s like this. Do it. Cool. Done. Done for the day.” With ‘Una’, is it different working with a director who’s got more of a theatrical background?

Well, I mean, they’re different. They’re different propositions. And so, I guess yeah, with Beno, we did a lot more sort of time around the table at the start of things as you would in a theatre production. But then, what we didn’t do was do the period where you move into the theatre and start figuring out who’s going to be moving where. So, yeah, I think for the days that I did on Slow West, they were very, very wordy days, too. So I probably turned up to Slow West not prepared enough to be doing those big tranches of dialogue and found it during it. Whereas with Una, I knew my way around the words very well and, yeah, that’s my answer.

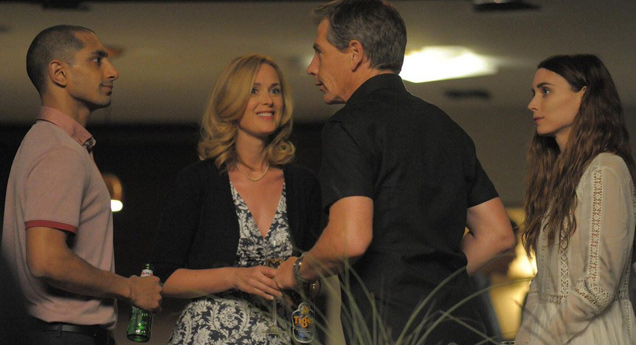

They’re different propositions for sure. Speaking of which, it was interesting to see you and Riz Ahmed sharing screen time. I don’t know if you do in ‘Rogue One’.

We don’t.

Were you in that environment with him? Or was this the first time you’d spent together on a set?

Are you talking about Star Wars, or are you talking about Una?

I’m curious about the contrast between a big film and and a small film.

Well, it’s sort of more fun and whatnot on a small film. But I didn’t get enough time with him on either of them, for my taste. I loved Riz. We shot Una before we shot Star Wars as well.

I thought it might have been funny to have gone through that big experience together and then do this little thing.

Do the big one and come back and do this… No. And it goes to show that we were incredibly fortunate to get Riz for Una, as we were with a lot of the cast on Una. So no, I didn’t really spend any time with him on Rogue One, as in we’re doing scenes together and stuff.

I guess it’s probably not really at the forefront of your mind while you’re making the film, but you’re about to show it to 2,000-odd people in the State Theatre here in Sydney. That’s a lot of people to be going through a pretty tough journey together. At what point do you start to think about the viewer and what that collective experience might be for them?

They’re the first people. They’re the only thing to think about. Everything else is irrelevant. It’s all about the viewer. That’s the only thing you think about. And I mean, the whole thing is about the viewer. They are the alpha and the omega of any of these things. So they’re always at the top of my mind. What do I think about them going through this bit or that bit? Well, I don’t think of it like that. But if I read something and I think it’s thrilling and it might work, then that’s the viewer. So it’s always the viewer. The viewer’s the only one that matters. We don’t matter. It’s the people watching it.

Ben Mendelsohn was a guest of Sydney Film Festival and Vivid Ideas.

Flicks Editor Steve Newall travelled to Sydney Film Festival as part of Vivid Ideas courtesy of Destination NSW.

‘Una’ plays at the NZ International Film Festival