Interview: Francis Ford Coppola on Apocalypse Now: Final Cut

The legendary director speaks with Steve Newall about his iconic film.

40 years on from making his Vietnam masterpiece, director Francis Ford Coppola revisited it (again) – and talked to Steve Newall about it.

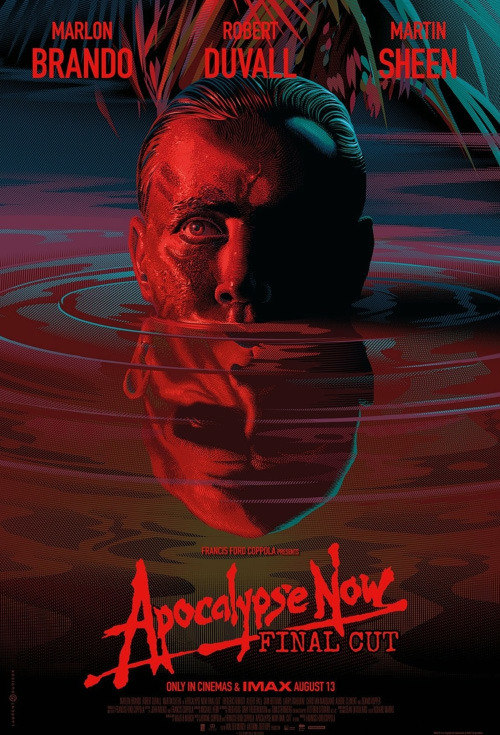

The definitive version of the 1979 classic, Apocalypse Now: Final Cut is a 4K restoration from the original negative and is available this week to add to your collection at home (on DVD, Blu-ray, and 4K UHD).

Legendary director Francis Ford Coppola spoke to Steve Newall about overseeing this new version of the film, and how time has altered attitudes to the film—both the public’s and his own.

We also have copies of the film to give away. Find out how to enter at the end of this story. Update: entries closed.

This feature first appeared in the NZ Herald to coincide with NZ International Film Festival screenings of Apocalypse Now: Final Cut.

For four decades now, Francis Ford Coppola’s Vietnam epic Apocalypse Now has made a mockery of industry unbelievers’ predictions of disaster during its infamously troubled production.

The film some Hollywood folks thought would never be completed has been hailed as a masterpiece since making its tortured way into cinemas in 1979. But as its 80-year-old director explains, it hasn’t truly been finished until now. Apocalypse Now: Final Cut is a new version of the film—its third—described by Coppola as “wonderful” and painstakingly restored from the original negative for maximum audience impact as the picture celebrates its 40th anniversary.

Jarring news footage may have brought the Vietnam War into living rooms, but Apocalypse Now hammered the reality home on the big screen. Exhaling a little psychedelic smoke into the fog of war, the film captures the surreal insanity and its confounding (and a little intoxicating) impact on the psyche. As Coppola tells us, this heady, confusing brew proved too much for the film’s distributors, who thought it too weird ahead of its initial release.

“We were under pressure to try to shorten it and to make it a little more ‘normal’ if I could use that phrase,” the director says down the phone. “We did the best we could because when a film first comes out you have no idea whether it’s going to live or die. It’s like a new baby that’s born and you have no way to know. And so I tried to make it as short as I knew how and as least surreal as I could.”

“Well, the film did come out and it did survive and it went through its first years growing and growing in audience acceptance”.

Having recently noted that “the avant-garde of yesterday is the wallpaper design of today”, Coppola recounted the experience that led him to reinstate previously unseen footage in 2001’s Apocalypse Now Redux. When, as the director describes it, he “took a peek” at it years later, playing on TV at an English hotel, his conclusion was that the film didn’t seem that weird to him by contemporary standards.

So, what’s it been like for Coppola to watch people and culture catch up to his films?

“I am very fortunate in that most of my films—with the exception of the first Godfather which was a hit from day one—most of my films have been released to a somewhat mixed reaction. There are people who find it interesting or there are people who don’t like it.”

“What has happened is, of course, over the years most of my films have withstood the test of time. And I’m very blessed in that people 40 and 50 years later are looking at films that I made as a young person and had received a much more qualified first reaction. Now, these films have become more classics and therefore they’re perceived better by the audience now than they were when they first came out.”

While Redux may not have been too weird for a 21st-century audience, its pacing proved a problem with some 49 extra minutes being added to Apocalypse Now’s already-substantial running time. “It was interesting” says Coppola, “but over time I started to think as a substitute version it was a little too long”. Final Cut strikes a balance between the two previous versions of the film, and Apocalypse aficionados shouldn’t be concerned that Coppola has followed in the footsteps of some of his New Hollywood contemporaries by over-tinkering.

“There are many, many, many parts of it that are exactly the same as in both films but it is more balanced. The overall experience I feel is much more effective because thematically and dramatically it is all-inclusive. In other words, it has sequences that the first version didn’t have but then again it doesn’t have sequences that the long version has. In my opinion, what it has is essential to its theme and story.”

Not many of us have the luxury of going back to what we were doing forty-something years ago as Coppola did when revisiting Apocalypse Now. The process may not have been as much of a nostalgic exercise as one might expect, but the way the director describes it hints this is to the audience’s benefit.

“When you’re working on a film there’s always two realities. There’s the reality of the scene within the story and there’s also what’s going on on the set all those years ago and if what was going on on the set is very depressing or you were scared or you were in trouble or you were arguing with your wife… Whatever it was, time is a beautiful doctor and as 40 years has gone by I don’t remember so much the emotions of actually the day of shooting and I’m more in the story as the audience should be.”

So are you seeing Kurtz more than you’re seeing Brando in scenes, for instance?

“Yes, of course. The director tries to put himself as more in the view of an audience and not think of who the personalities were. A motion picture is an illusion and you’re trying to create an illusion for the audience so the audience can embrace it and the audience is who contributes the emotion. The emotion’s not in the film, the emotion’s in the audience and the film is the magic illusion that seduces them into expressing it.”

Speaking of seduction, at the time we spoke, sabre-rattling in the Persian Gulf very much gave the impression that the United States was spoiling for a scrap with Iran, and trying to suck the public into supporting an attack. I asked Coppola if his 40-year-old film, which shaped so much of how we still picture war today, holds any lessons as another unwise conflict and potential quagmire loomed.

“Well, I always wanted Apocalypse Now to be a film about morality and about the strange way that morality is expressed and how morality is often used by very righteous organisations which then perpetrate the most horrible sins. So to me the key sentence in the script and what I thought Apocalypse Now had to examine was the sentence—and pardon my bad language—there’s a quote where he says, “We teach the boys to drop Napalm on people and yet we won’t let them write the word fuck on their airplanes because it’s obscene.” That to me is the gist of what I was looking at in my examination of morality.”