I’ve Always Wanted To Do That: Valentine’s Day at Hanging Rock

By recreating classic movie moments that look so cathartic onscreen, Eliza Janssen hopes to improve her own life. This Valentine’s Day, she just had to try the ethereal outback ascent seen in Peter Weir’s seminal Aussie new wave film Picnic at Hanging Rock.

“Whether Picnic at Hanging Rock is fact or fiction, readers must decide for themselves. As the fateful picnic took place in the year 1900, and all the characters who appear in this book are long since dead, it hardly seems important.”

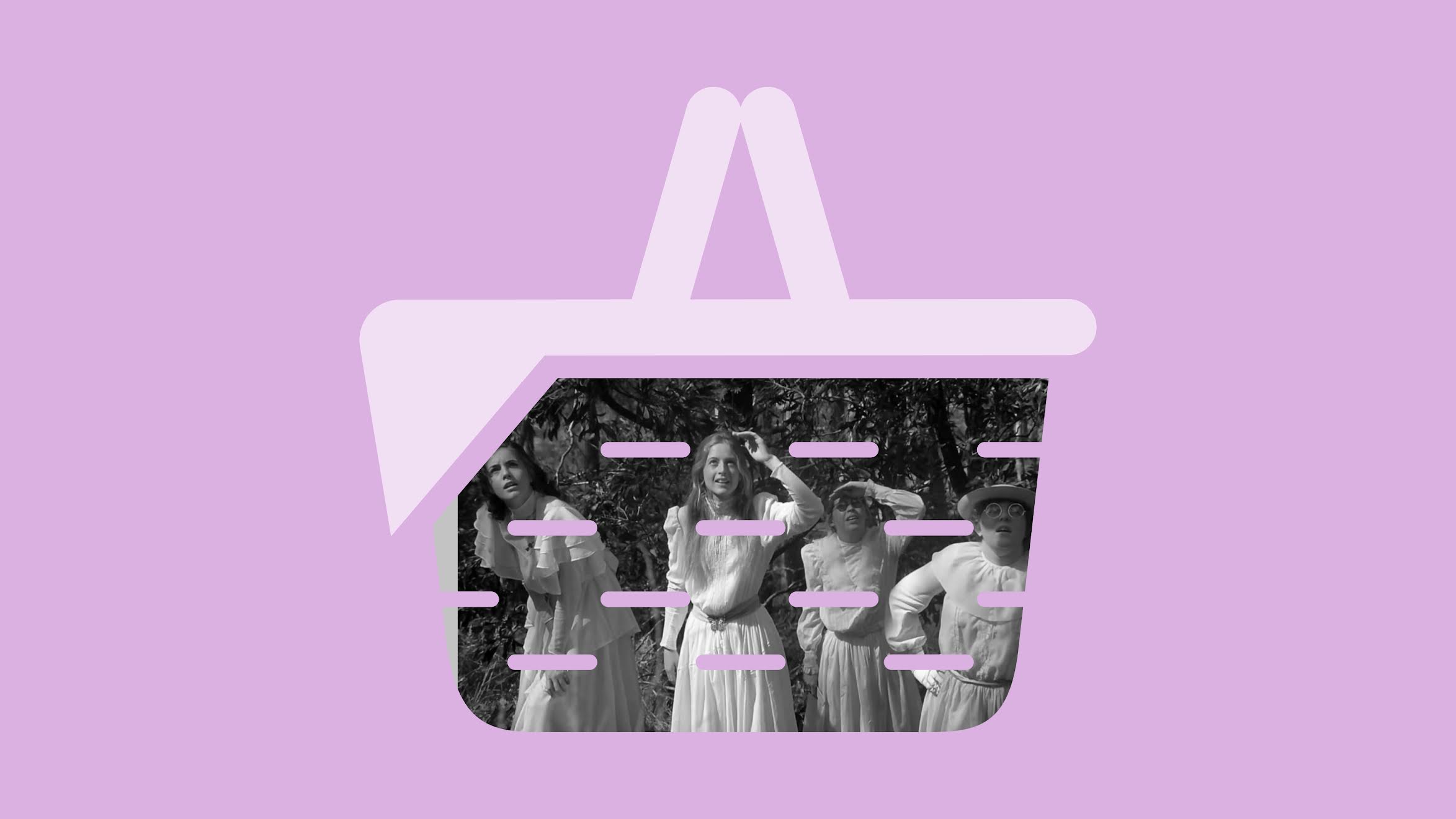

So begins Joan Lindsay’s novel, adapted with dreamy romanticism by Peter Weir in a 1975 film that opens on a title card with the same impish dismissal of historical accuracy. Makes it hard to shame anyone for believing the haunting events are factual: they can truly seem like some Victorian horror story of ‘the colonies’, lost to the tides of time.

Even the visitor centre at Hanging Rock, nested in rural Victoria’s Mount Macedon, plays coy as to the story’s authenticity. 123 years after the setting of Lindsay’s novel and Weir’s enduringly bewitching film, my mum and I are bamboozled by large text on the building’s walls, seemingly touting that three schoolgirls and their teacher did disappear from the rock’s summit.

We’ve been meaning to do this as a Valentine’s Day excursion for ages, driving a quick 50 minutes from Melbourne’s CBD into the stinking hot summery landscape of Macedon. Little did we know that the rock was formed of igneous volcanic layers of mysteries upon enigmas upon bizarre coincidences, evoking a sense of wonder just as tangible as the tale’s intangible nature.

We know that Lindsay wrote the novel over a feverish two-week period, dreaming the plot at night and writing it without pause during the days “like a demon”. We know that the time fuckery of the tale begins right from that first page (the calendar of 1900 shows that Valentine’s Day should’ve been on a Wednesday, not a Saturday), quickly setting up one of the story’s most evident themes, of ancient memory and the fluidity of time.

In Hanging Rock: A History by Chris McConville, the 6-million year old mamelon (a volcanic formation suggestively termed after the French word for “nipple”) is described as an important ceremonial site for its original Wurundjeri custodians. “Marriage…initiation ceremonies…and the inter-clan practice of exogamy (marriages across territorial boundaries) made Hanging Rock critical to ensuring stable inter-group connections,” McConville explains. This goes completely unmentioned in film or book, save for the eerie similarity of the girls’ disappearance taking place on Valentine’s Day—the invading culture’s day of romantic significance.

Save for a third-act suicide by forgotten student Sara Claybourne, Picnic at Hanging Rock is never violent—explicitly, at least. The film adds disturbing, masochistic dialogue exchanges, such as a doctor intimately inspecting wimpy survivor Edith after the ordeal and declaring her “intact”, and one gardener joking that the missing girls may have been “kidnapped, or…you know”, trailing off with a wolfish smirk.

But modern viewers might find what’s not said or shown more dark than anything we do see: who lived and perhaps died here, so that the abusive Mrs Appleyard and the nearby town’s landed gentry can tramp on the ancient lands, in whalebone corsets and clattering wagons? Gheorghe Zamfir’s ear-and-heart-piercing panpipe music suits the environ far better than their diegetic classical compositions, so stuffy and out of place against the bush’s unknowable depths.

The more I gaze at the rock, though—on screen, page, or even in person standing below it—the more it reminds me of one of my other favourite, endlessly interpretable movies, The Shining: in its gauzy, atmospheric profundity, it’s really about anything and everything. Class, gender, repressed eroticism and queerness, indigeneity and colonialism…all captured through a literal veil of glamour by Weir, who filmed his new wave Australian classic with a bridal veil over the lens to achieve that ethereal aesthetic.

After rewatching the movie, my mum and I were prepared to pant, sweat, and scream our way up and down the rock. Alas: the path up to the summit is extremely accessible, with practically every dirt path between the massive formations ground smooth by centuries of foot traffic. Once we’d snacked on berries and our own shabby recreation of the schoolgirls’ St. Valentine cake, we made it up to the summit and back within 40 minutes.

It was a perfect day (until our car got a flat tire on the way home), and I’m alternately relieved and bummed out that I didn’t sense any of the magnetic, infinite evil that some visitors have experienced before the rock. My February 14 basically went like a more boring version of Lindsay’s novel and Weir’s film, as if Miranda, Irma, Marion and Mrs. McCraw just toddled back to the group anticlimactically after lunch. I can’t recommend the trip enough if you happen to be near Melbourne sometime: within an hour, you could be out past the airport, wandering up amongst prehistoric eucalypts and ferns in your own dreamy “display of tomboy foolishness” that the girls’ headmistress so sternly warns against.

Super-fans might be aware that Lindsay released the excised original ending to the book in 1987 (“chapter eighteen”), but as with any work founded on such potent, poetic mystery, Picnic is best left as just that: one big, romantic unanswered question. The answer I’m really dying to know is why the hell Picnic at Hanging Rock is so difficult to stream anywhere??! It’s enough to send a girl screaming down a mountainside, lace trim flailing in the hot February breeze.