Judy & Punch director on her made-up tale about real-life misogynistic puppets

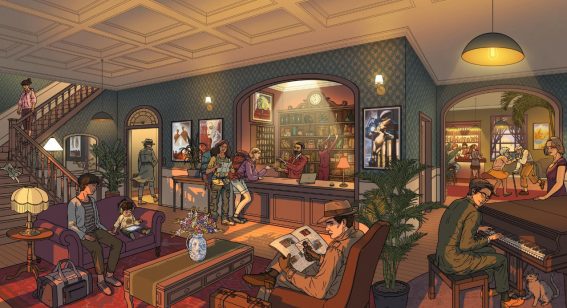

Mia Wasikowska is one half of a puppeteering duo (The Nightingale‘s Damon Herriman is the other half) going through tough times in Australian actor Mirrah Foulkes’s feature directorial debut. Nominated for the Grand Jury Prize at Sundance.

Currently playing as part of the New Zealand International Film Festival ahead of its nationwide release, Foulkes talks to Flicks about the film’s unusual tone, the misogynistic puppet show Punch & Judy, and making up an origin story.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

FLICKS: About 10 minutes into Judy and Punch, you could fool anyone into thinking you’re watching a very dry, serious Tom Hooper-directed period piece biopic but it totally isn’t that. Was it early on that you chose to make it comedic?

MIRRAH FOULKES: I don’t know if it was even really a choice. I started writing, building the world, and it was pretty clear to me that I wanted it to sit inside the kind of absurd, satire world—without being too heavily a counterpoint to the more political elements of the film. It was pretty much from the get-go that I wanted to do that. But through the writing process, the tone led through to what I wanted it to be, in a sense. It sounds a bit spacey, but it kind of developed organically.

There’s a nice parallel between the misogynistic Punch and Judy puppet show itself and that particular era where witchhunts were going on for absolutely ridiculous reasons. You find black comedy in that, which is important, because black comedy can be pushed too far or not far enough. How did you manage to find the balance?

It was a combination of trying to find the balance in the writing, the performance, and then in the shooting style. But I very deliberately wanted to make a movie that felt tonally unusual and that shifted.

It’s not consistent in its tone, I don’t think, and that’s quite intentional. I liked that idea of taking an audience in one direction and then very quickly sideswiping them into another to throw you off. From the beginning, that was something I was interested in exploring because it’s something I’m really fascinated in when I see other films that do that.

And what about the editing process? Were there ways you modified the timing or something to make a joke really land?

We came about really moderating it. At one point, I remember during the cut we were working on the rhythms, pacing—all of this stuff—and I remember stopping and thinking, “Oh, shit. It’s not funny. We’re sucking the humour out of this somehow, we’re working too much on rhythm and timing and somehow we’ve lost some of the comedy.” So then we went in and did maybe two or three weeks of doing a comedy pass going, “How can we make this funnier?”

That was a really interesting exercise for me. I’d never done that sort of thing. And there’s so much you can do in the edit. Comedy’s so much about how you time that stuff out.

You got to tell whatever tale you wanted to, right? It’s not based on the actual Punch and Judy history. I don’t know how widespread the release has been so far but have you had any Punch and Judy fanatics contacting you?

Oh, there’s people out there who are really into it, obsessively into it. Makes me a bit nervous actually when we go to the UK especially because I’m really screwing with the historical accuracy here.

I mean, like you say, it’s a fictionalized origin story. I’m making stuff up. I’m creating something that I think is fun for a movie and speaks to the kind of political allegories that I think are interesting. But it’s certainly not been strict about the history of it whatsoever. So I don’t know. I might have some angry Punch and Judy fans in London but so far, no. Just people that are really into puppets.

Did you know your own voice before starting this feature film or do you think you were finding your voice as you were making this film?

I’ve been thinking about this a lot. I’m not sure that you ever really know your own voice, and this is just, currently, today’s perspective on it. But I have a lot of people say to me that, based on the shorts that I made, and this film, they’re like, “Oh, it’s so you. It’s so of you.” And there’s something so specific about the work that you can do and you can tell it’s your work, and I don’t see that. Perhaps that’s because I’m inside it. And I hope that that’s a compliment in that it means that I’m working from kind of a truth or whatever.

I’m not sure, but I certainly have no sense of what my thing is really. I have no idea what it is.

I can certainly look at other filmmakers that have a really clear distinctive sort of throughline through their work, and I admire that, and I would love to feel like I had that but I don’t. There’s nothing premeditated about the things that I choose in order to try so far.

I guess it just happens. It evolves organically out of the material you’re drawn to and the way that you write if you’re a writer and the way that you make things when you’re a filmmaker. But I have no idea what that voice is, maybe someone else can tell me.

That’s why we have critics, right?

Oh God, that’s a whole other can of worms [laughter]. That’s why you talk to people at the end of the screenings. That’s what I love. I really love trying to get honesty out of people, which is not always easy. But some people are more open and honest and blunt than others. And trying to get a sense of what peoples really genuine experience of the film was like.

It’s easier to be blunt on the internet.

It’s a lot easier, yeah. It’s easier to be cruel on the internet. I don’t read any reviews. I’ve made a very firm rule on this movie. And I think I’m actually a lot better for it. I just decided that it wasn’t a healthy thing for me to do in this very early, kind of fragile creative place for myself.

I don’t know, maybe I’m sticking my head in the sand or something but maybe later down the track I’ll go back and read some stuff but I just didn’t feel like it was healthy. What I felt like was healthy for me was to talk to people after screenings and stuff.

You described the puppeteers in the film as being really into their craft and very serious. I was wondering if Damon Herriman actually saw these puppeteers and maybe moulded parts of his character off them?

Knowing Damon, I wouldn’t put that past him at all because he’s so astute. He’s such an amazing character actor and he’s always just implanting little details into his work. And often doesn’t need to talk about them or brag about them or have you even aware of them. He’s so detailed like that.

Mia Wasikowska had to learn a lot of different skills, not just puppetry but also magic.

And we cut most of it from the film [laughter]. We shot a couple of coin tricks that she did and a disappearing ribbon trick. But so often you trim the heads and tails of scenes and that sort of stuff. If it’s not story, then it’s not essential.

Did you get her to learn anything else?

Oh, I made her skin a rabbit. Yeah. That was tough. She hated it. She hated me for making her do it. And I don’t blame her. I would have had a really hard time doing it as well. It’s pretty awful.

There was also one shot of a dead rabbit with a maggot coming out of its eye. How did you achieve that?

Our trusty maggot wrangler.

So that’s a job?

Yeah. Art department. Yep, yep, yep.

So they just wedge a maggot in the eye and wait for it to wiggle out?

Yeah. We spent a lot of time wrangling, corraling little maggots. I shouldn’t give away all the secrets, but we thought we’d just sit them on the dead rabbit and they’ll kind of burrow in. But they did the opposite—they tried to run away.