Kiwi Filmmaker Sarah Cordery on Noam Chomsky, Israel, & Her Film ‘notes to eternity’

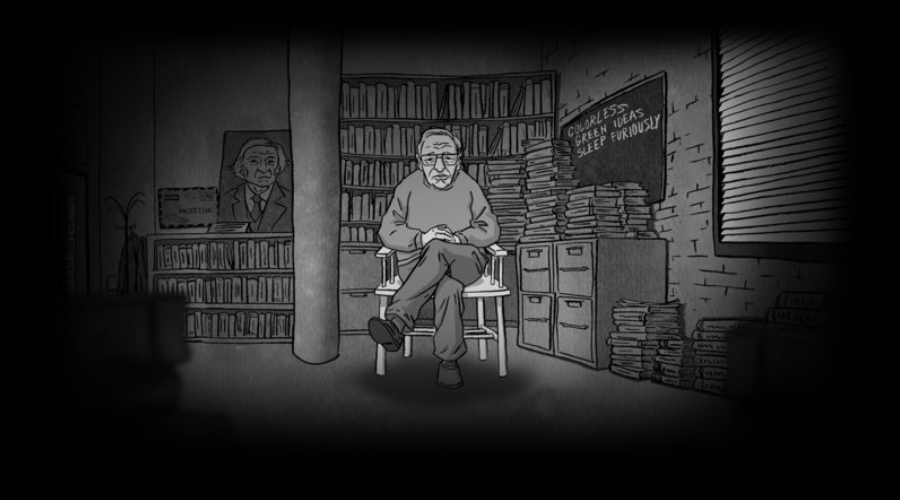

The minds of renowned critics of Israeli policies – Noam Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, Sara Roy and Robert Fisk – form notes to eternity, a documentary from New Zealander Sarah Cordery exploring the personal and historical perspectives to their arguments. It is currently playing in cinemas nationwide, so we picked Cordery’s brain about the feature.

FLICKS: How were you feeling about the project at the beginning, the middle, and the end of it?

Sarah Cordery: Well, at the beginning of it, I realised the massive agenda I had in front of me, and I went at it hammer and tong in terms of research. When I actually started filming, I had sort of a cast of thousands that I was looking at. I felt it was something that was going to define itself once I’d got well into it, and that’s indeed what happened.

In the middle of it, I was pleased with how things were progressing, but I was also very frustrated because the enormity of taking crews overseas and approaching this subject with the depth with which I wanted to approach it, in the way in which I wanted to approach it, of course was prohibitive in terms of cost and logistics and things. So there were times when I felt like, yeah, this project was just too huge and I needed more financial assistance, I guess.

At the end of it, which was like yesterday, I’m very relieved [chuckles].

How has the shape of the film changed over that time?

In terms of the way in which I’ve structured [the film], each character has their own separate part. There [are] no overlaps.

I mean, Sara and Norman refer to Noam Chomsky, for example, but aside from that, there’s no direct conversation that’s going on between the characters. They have their own little worlds within these five chapters. And so that was something that came to me as I went along.

I felt that these were such strong individuals and they had such individual stories to tell and different approaches. I think as well that Fisk said to me once that he doesn’t want to be part of any group. And I can identify with that, and I wanted to keep their individuality intact within the film.

That is a very interesting viewpoint of Fisk’s. And I think when you look at a lot of his coverage, it does focus on the problems of group-think or being a part of a contemporary alliance of some kind and how that can change.

Yeah, and so he feels that when activists come to all his talks in droves, and they ask him direction, he says, ‘it’s not for me to tell you what to do’. He doesn’t see that as his job. And so in a sense, yeah, I really wanted to respect that.

It also plays into the issues of perspective and memory and identity and recollection of things that I play with in the film in various ways. Well, they there if you look for them, the notion of subjectivity and ways of framing the world. Hence, the film is quite impressionistic, which may surprise some people – being an issue film and also having these strong thinkers on this issue – to make it that way.

There’s so many entry points to this topic. You can approach it from your pre-existing political or cultural standpoint; you can approach it from a journalist’s standpoint, or an intellectual standpoint. What’s your entry point?

My trajectory was always to make a film at some point; it was just a matter of on what and when. And when I went to the Middle East, I didn’t go with the intention of making a film; I just went to have a look, basically. And I was very interested in the aesthetics of landscapes [chuckles], funnily enough.

It was rather an inarticulate interest, and it’s become clearer to me now what that was about. But the West Bank in particular encapsulated that, and I had this opportunity of driving through the West Bank. I had a job when I first arrived teaching English at the British Council, and they wanted me to go up through the West Bank every day, in their car alone, to Nablus and hold a class there.

And so I had this opportunity, a unique opportunity, on my own to travel through this landscape. I mean, I wasn’t tabula rasa but I didn’t go with any particular agenda, and I think that’s a strength in the genesis of this film – that I didn’t go over there to tell a political tale. I just went there and I observed.

But I’m also very conscious that you don’t want to aestheticise suffering and oppression and that’s very clear that that’s what’s going on over there. And land is always very politicised. So my entry point was looking at the marks of the ongoing process of erasure that are very apparent there. I mean, it’s a very broad inpoint, but that was my inpoint, if that makes sense to you [chuckles].

For sure. What we’re used to seeing of the landscape and environments is times-of-conflict news reel footage more than anything else. It’s quite refreshing to see just shots of a highway and some landscape in your film. But apart from the actual degradation that people have to live among, did being in the native environment help shape your thoughts about the conflict and occupation?

Yeah, definitely. I mean, as I said, I went with this very broad interest. You know, how the land bears the marks of this erasure – it’s like an open wound. And when you start to explore that, the layers of history. There’s a whole lot of things that feed into that.

But what struck me probably most acutely was it’s a very diurnal thing. It’s not the stuff that you see in the news reel footage. It’s just this everyday grind, the little things. It’s the little things that add up and more so than the obvious violence. And that to me encapsulates the devastating consequences for the Palestinians. It actually unpicks just the very fabric of their everyday life, just the ordinary things.

The film took shape in response to this erasure and also the historical and political narratives that have enabled that. I started to explore that quite deeply, and that led me to people like Fisk and Chomsky.

I think partly because you haven’t set out to make a polemic on the subject, you give your subject a lot of time to breathe, and you give the individual subjects within the film time to breathe as well. Because they’re academics, because they’re verbose is it difficult to mine through for the content that you need to make your documentary?

Not in my in-person interviews with Noam Chomsky – I did six of them – not at all. But in terms of mining through his public talks in particular and also reading his material, I found that very difficult.

I think it was in Manufacturing Consent possibly, where he refers to this, or in Rebel Without A Pause that– his aim is to be ‘boring’. It’s not his aim to entertain and he doesn’t like the cult of the personality. But in fact, he’s a very engaging person in person. And he’s a keenly civil man. Yeah, I found it difficult [chuckles].

If you look at my workbooks and my transcriptions from his talks, I had this quite idiosyncratic way of mining my way through it because he goes off on multiple tangents all over the place, and hanging onto it and trying to navigate through it for the film, that took me time, yeah. Definitely.

The film that may often come out of this process is really just looking for bites from its contributors and bites that support a narrative that’s already in place, right?

Yeah.

So perhaps in the context of a ten-minute interview with some of these talking heads, the director has a very specific objective of what they want to get, whereas you’ve approached it really if anything, completely the other way around.

Yeah [chuckles]. That’s astute of you. And maybe it’s just completely obvious. Yes, I’m actually proud of it. I’m proudest of that because I think that it’s often in those spaces between image and idea that the greatest potential for understanding and revelation come. So I wanted to kind of absent myself.

At the end of my interaction with the region, I had very strong ideas about it, but I feel part of my job was to take myself out of that. That’s why I’m not a John Pilger type figure in my film or anything like that, and I don’t have his status. But you know, I think some people might want to plant themselves in there in ways.

If I’m there, it’s just in a jokey sort of way. Yeah, I noticed there was a reviewer who saw a test screening at the NZIFF in Dunedin and he honed in on this: the space that I create for people to express themselves and also for the audience to find themselves within that.

And the space for your subjects to dictate what ultimately shapes the film rather than you just cherry-picking the perfect quote to support the structure.

Yeah, a lot of that came from spending time with Chomsky and reading Chomsky. His absolute distaste for concision, which happens in the current media environment – necessarily perhaps. But just people taking events out of their wider context. And I think that’s what happens all the time with the Israel-Palestine thing: much of what you see is just these little cherry-picks used to shape a particular narrative.

And it was really difficult – at times, I was tearing my hair out – to just try and create a film that didn’t do that. That’s why I say I’m proudest of that, because it was so difficult [chuckles].

In the case of Robert Fisk, he’s a fellow that can oftentimes be difficult to read because he has got such a way with words, of painting a tragedy and really conveying anger and suffering through his writing. And obviously with him on the ground and being able to walk through scenes of death and destruction, boy, that really ramped it up for me, and that was some of the hardest stuff in the film for me to watch. For you shooting it, what was that like to actually walk around some of the sites of mass killings?

Oh, awful, awful. But he was a dream to work with in many ways, in that obviously he’s used to doing this as a journalist, just expressing his thoughts on the ground. So when you talked about was it difficult to cut him and Chomsky– Robert Fisk, no, because he kind of understands the medium and because he is so surefooted in his delivery, it was just easy. And that’s why I let him have those particular scenes like the Qana scene.

I think in the film festival screenings, we didn’t even cut it; it was just one long uninterrupted scene. And it’s virtually that still. Sabra and Shatila also. I just felt that that encapsulated who he was and how he is in that environment. But, yeah, personally, I find watching that Sabra and Shatila stuff just devastating. It’s terrible.

There’s that environment I think probably just broadly being in the region walking around with a camera, it must come with maybe concerns, or certainly it would be an atypical environment to be walking around and shooting in, yeah?

Yeah, in various ways it is. I think in the film– this is probably not what you’re asking, but I wanted to be very clear that I’m not telling the story for the Palestinians, so I tried to foreground the way that the camera’s just passing through the land, which is effectively what we were doing.

I talked earlier about not wanting to aestheticise suffering. It’s something that’s familiar in the canon of colonisation, where a particular group of people are framed in a certain way. And in a sense, I’ve tried to highlight that by questioning whether or even implying that at some level we may be doing that. Like the tracking shot through the ‘Beach Camp’ refugee camp in Gaza, for example. I don’t know if you picked up on that or not. But, yes, just in terms of working on the ground, which I think is what you’re asking, yeah, it was.

Yeah, I suppose I’m just guessing that it’s an environment where a camera with a lens and where the idea of an audience taps into a very, very long legacy of coverage of the region and the various arguments that people are trying to convey to the outside world.

Yeah, and there is that scene in Sabra and Shatila where that kid says, “It’s a Jewish broadcast.” And then the old woman accuses us or just says, “You’ve taken our land,” and all of that. Yeah, it’s what a camera signifies to them. And at one point, I think one of the crews I was with in Gaza, as we’re leaving after an interview – you know, sort of things can turn on the head of a pin – we were sort of pelted with pebbles. And these are all understandable reactions.

But, yes, all the time, I felt conscious of– and we discussed it with Moussa, Norman Finkelstein’s friend. We had a camera in his home, for example, and he was very relaxed about it, but it’s the same deal really. It’s like, “What are you doing?” So I let Norman tell that story: what are we actually doing coming back each time documenting the suffering? I find that quite a powerful thing in the film. But Norman has the courage to actually say [chuckles], “What if I stopped doing this? Nobody would buy my books,” and things like that.

It’s like there’s a whole industry involved in that, and it is a mecca for the news media, and they can seem like vultures on a carrion a lot of the time.

Absolutely. Another one of the environments that’s charged with high level of tension in the film are the Q&A sessions where people are barraging Chomsky with some very interesting requests, like, “Will you join me in reciting the Pledge of Allegiance?” What a strange environment. Does it legitimately feel like it seems in the film, like people are attending deliberately to tear strips off the speaker?

Yeah. Yeah. There’s definitely that, and I asked Noam Chomsky about that on one occasion and he said, you know, people leak stuff to him about these organized attacks.

It’s often the same people doing it. And sometimes there’s these concerted efforts to attack him. That’s why one of the early scenes is that professor from Boston University walking along the road with a captive student going to a talk by Chomsky. Somebody had told us about it, so we went there, and it was Hillel House, which I don’t know if they’re in New Zealand, but on campuses around America, it’s where young members of the Jewish community can congregate. And so this was at the Boston University Hillel House, and they all had their placards, getting them ready, and there was talk about how they would respond to the questions, et cetera, and I saw them at various different talks. They’d come and they’d ask their questions and some more adroitly than others [chuckles].

Is it Chomsky’s reach that brings the negative attention? Is it that he’s a figurehead for the intellectual criticism?

I think he just frustrates the hell out of them because he keeps his cool, as you see in the film. And he treats everybody with respect, even the guy, the Pledge of Allegiance guy. Everybody else was falling about laughing at him, and Chomsky takes him on seriously. And I think it’s just that he refuses to be pigeonholed. Yeah, I don’t know. He just has this reach and has done so for a significant amount of time.

I mean, he’s come in for flak from both sides. You know, even from some Palestinian activists. He comes under attack from them because of his position on the right of return and the one-state settlement that many of the more radical Palestinian activists are advocating.

In the film I think this is what you’re getting it – he says growing up, he aligned with various leftist groups, et cetera. And then at the end of that spiel, he says, “And then I just did it on my own.” And I think that’s what he does. He’s unique. He just ‘does it’ on his own, and you can’t pigeonhole him easily, or he won’t be pigeoned. If you take him on personally, he a formidable debater. I mean, I guess you can do it in a media environment, with sound bites but yeah that’s another story.

I’m going to leave you with one last sweeping question which is after the process of making this film about a region that has millennia of conflict, but in terms of the subject of this film, about a century of state-based grief – the erasure of a people; all the awfulness that you’ve witnessed – has it affected how you see New Zealand’s colonial legacy?

Well, definitely, the analogous situation, Steven, to this film, and the Native Americans and also what happened here with Maori. Yeah, I do feel that quite keenly, and perhaps more keenly at a personal level how it must feel for Maori who have experienced such loss.

There’s a raft of unforgivable things and unrecognised things, and I think, yes. I think the film speaks to that, and it speaks to other colonial situations, be it in India or the Native Americans, wherever. It’s the same story; it’s a very old story, and they have things in common. The commonalities are “uncontroversial”, as Noam Chomsky might say.

‘notes to eternity’ Movie Times