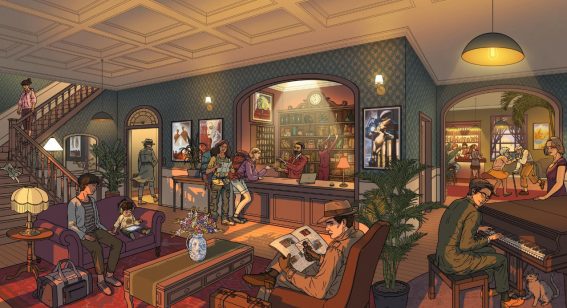

Leave No Trace director Debra Granik on her spellbinding film

Here in Aotearoa for NZ International Film Festival screenings of her phenomenal new film Leave No Trace director Debra Granik (Winter’s Bone) joined Flicks for an in-depth discussion about screening the film in front of audiences, her affinity for non-mainstream lifestyles, and her superb Kiwi lead Thomasin McKenzie.

FLICKS: Do you take the temperature of audiences coming in and out of the room? Obviously, you’re not sitting there hanging out for every single screening of your film, but do you get a sense of a certain bustle or energy from the audience?

DEBRA GRANIK: Well, certainly, if there’s a Q&A, and there was a Q&A. It was really interesting to hear very specific comments and questions about the film. So I feel like that is my main way of understanding what people felt was impactful or what questions it raised for them. Parts that maybe were an enigma or confusing, you get to hear the wealth of ideas. And I think Q&As are excellent because the questions change a lot. It’s refreshing.

I think sometimes in certain phases of trying to promote a film or bring it out into the world sometimes it feels like there’s this one period where the questions might be really similar. Because they have to be. They’re factual. You need to get certain information out about the film. But with an audience, I feel like frequently the questions become very diverse. You can hear a question you’ve never heard ask before. It’s just keeping it very fresh as a responder.

What’s an example of that from the other day, or just at an audience Q&A in general?

It’s not that I have never heard it before, but that when it’s asked in a different kind of voice, a different place, a different time, it was the decision to not include a lot of backstory for them. And then that led to an interesting discussion about the comfort zone.

Some people when they respond to a story need a lot of backstory and really want that. Other people can make the effort or swing with the idea that they’re going to piece it together as the film goes on. It’s very related to how we process information on some level. I was trying to answer it in a way that I’m not leveling a judgement, but I’m interested in what different kinds of storytelling needs are. And so that led, for me, to a good moment of contemplation.

Writer-director Debra Granik

Do you balance the idiosyncrasy of, “I want to make this thing. This is my idea and I’m making it,” versus, “This is what I think people are going to need from it?”

All the time. I am trying to be an accessible filmmaker. If I was a pure experimental filmmaker, or a person who copped the attitude, “This is my genius and who the hell cares who gets it?” I’m definitely operating on a different system. I’m making films that are about ordinary life, and therefore, I want them to have an ability to translate and be accessible to another person who’s just living in the same times I’m living in.

Just thinking a little bit more about the audience question about backstory, and I think to me that might kind of relate to ideas of what the beginning, middle, and end of ‘Leave No Trace’ actually are. And I think for some people, the beginning would be first going into the wilderness. We’re maybe not used to seeing narratives that begin in such an unusual place, I guess, for a broad audience.

Right. And without a lot of context, right? So I think one of the big things that challenged us in editing was it could look like a camping trip, right? We needed to go to great lengths in a subtle way because we weren’t using expository language to define it or to give it a setting. We had to drop a little context so that you understood they were living there, not just camping. Because the first few minutes of the film it could be a camping experience, right? So that was tricky how to get that to be understood.

And for some people it may not even be completely clear until the social worker actually says that upon their discovery. “Where do you live?” And she says, “Here.” That could be the first concrete moment for somebody. It could be earlier. That you see that they’ve gotten groceries in a way that doesn’t look exactly like camping.

The way you’ve shot the environment and the landscape is gorgeous. You’ve captured it in a really stunning way, it dwarfs and almost overwhelms the characters that are in the shots. There’s an interesting scale thing where they are just small creatures in a big environment. Was that deliberate, or is that just something that I’ve taken from it?

Because the forest was of a great height, I knew that it would be visually interesting and dramatic to show the grandeur of that particular part of the forest, and to show that there was a massivity amidst some old-growth trees. And that, of course, is not the entirety of the forest.

Much of forest that looks like that has been felled, so it actually is poignant that they would have to live on a park in order to live in such a grand forest. The actual so-called big forest is mostly gone. So I did want to show its monumentality, and I wanted to inspire that feeling in us an awe. Like, “Wow.” We are much smaller and we’re part of the statistics on that park, they list it. I forget, but 62 mammals. 152 insects. Just in that particular little piece of land on one particular continent. Those are the moments where you kind of almost feel a serenity. Sapien are one of the 62. We’re just 1 of the 62. I did feel excited if the photography could kind of suggest that. I was into that.

What challenges do you have shooting in an environment like that? One thing that strikes me is it looks so great on the screen. There’s textures and nuances in an environment that I would imagine look incredible with the naked eye, but is it difficult to capture in a shot in a way that evokes the same feelings?

That’s the magic, and potency, and pleasure zone of using lenses, right? Because they amplify or distill what we see. So you’re quite right, our vision is, what, 180 degrees, kind of? And so then with lenses, we decide what we’re going to focus and ingest. We can make that wider. We can make that narrow. We can make that macro.

We can see a spiderweb in a way that you can’t really walk up and see a spiderweb, right? You can’t walk up to a spiderweb and see it both up close and large. You can see it up close and see a small segment, but then to see it projected, you get to see the full geometry, but you also get to see the iridescent colors that are displayed when light hits the silk. So all this extra augmentation are what lenses do. They allow us to see what the human eye can start to see and they amp it up for us.

There’s a lot of visual pleasure in filming the natural world, of course. And I had to be careful to not go into National Geographic world, right? Meaning there’s a point in which nature photography doesn’t appear that you’re finding it sort of on your own accord. I love seeing anything David Attenborough’s ever done. Anything that Nat Geo’s ever put out. And I’m someone who will always derive pleasure from seeing nature photographed. But in terms of naturalism, you can’t actually start to populate your film with so much of this imagery because it would start to seem like, “Oh, wait. It’s not possible for them to really encounter those things.”

The film had me thinking about how many narratives there are about running away. New Zealand’s got our versions of it. The expression “going bush”. And it’s romantic and it’s attractive. But obviously, in your story, it’s not really so much the allure of the environment. It’s a push away from society rather than a pull to that.

Do you feel that the film pushes against some of those romantic notions?

I think so because as you say they’re trying to pull out from something. So it’s not just a lifestyle change, or an expedition dare. It’s not like saying, “Let me climb a mountain.” Get some expensive gear and do this because it’s a personal challenge. And I’m not trying to diss those things. And there’s films about people that try feats. An ascent to a tall mountain, or hiking a very large amount of trail. Or even introspective journeys, right, where someone’s had to seek out a challenging lifestyle because there’s some issues they’re working out. And to some extent, that’s what’s happening here.

This individual who is traveling in this part of his life with his daughter is feeling alienated from the business as usual of a mid-sized American metropolis, or a city, or town. And he’s saying, “Okay. The way that I calibrate, the way that I can make my life work, the way that I know how to operate well and be a good teacher to my daughter is to live a very reduced and simplified lifestyle where I know how to operate because the amount of elements I’m trying to sort through are delimited.”

He’s also wanting very much to go against some of the pressures of consumer capitalism. He would like to live with less objects with less material weight. So in some ways, he’s trying to be undetected. He’s trying to find a niche where you could live maybe more in accordance to your own thoughts of what would make sense for your lifestyle. But if you’re not a person with property, you don’t really get to choose that, right? Someone who would like to live an alternative lifestyle who owns a little parcel of land can go do so. They can set up some solar panels. Their needs for energy and shelter can be satisfied, and they’re not going to be booted off their own parcel. But he’s in a different predicament.

Ben Foster’s character has put his daughter in a specific situation, but this is a story of her finding how she fits in. That’s another thing that goes against, I guess, some of those more romantic versions of running away from things.

He’s showing her one way, which it to extricate and to simplify, and then she has to go on her own journey of curiosity, which is really what we call coming-of-age, right? To be curious about what are the choices on this planet. How do people choose their method of existence and their survival techniques? So she’s been shown one set from him, and then, of course, like a positive Pandora, she’s going to be opening these boxes and looking in like, “I see that. Oh, I see that. Oh, I’m noting this here.” And then she’s got to adjudicate and feel her way through, “what draws me?” So you’re absolutely right that she has to then go through this kind of seeking phase of, “how am I going to put my life together?”

That performance conveys so much of the emotional narrative of her character. There’s so much conveyed through nuance. And she’s able to depict a really strong emotional life by not doing very much.

How do you direct for that? Did you see that latent in her as an actor, and then how do you direct that to get that result on screen?

So Thom, as a young woman, is absolutely, I would say, by nature a curious person. A receptive person. She’s not jaded. She’s not like, “Been there. Seen it.” Or, only in her device. She’s always looking. Always making observations in her real day-to-day life. And she brought that to the character. So she’s not someone who just has her head buried in one part of human life right now called social media or whatnot, so I didn’t have to somehow come up with big tropes to dig that out of her. She comes with that. And so I think it’s very visible on-screen.

Then I think the fact that she was in a different environment, as a Kiwi trying to do this entire imagining in Oregon. Like you say, there’s some resemblance. The forest can visibly look a little bit like there’s some kinships here with the emerald green, and the moss, and whatnot and the sword ferns. Be that as it may, she had to listen to different accents, and different dialects, and different idiomatic things, and idiosyncratic things. And so she had to stay attuned. I think that also helped.

I think the fact that she was a foreigner made the Thom-ness of it, who’s feeling like a foreigner sometimes in these new environments, right? She doesn’t have it all wrapped up. She doesn’t know everything that the other teens that she meets know. And so maybe those two things really facilitated her being able to take a really fresh take on her journey and then you feel that on screen.

There’s a lot of time where it’s just her on screen. When you’re working with basically your actor’s emotional responses to what’s happening around them, so it’s not dialogue driven, and it’s not even necessarily very action-orientated.

Do you find that in edit, or do you know what you need from each specific scene in terms of exactly what that mini emotional arc of the scene looks like?

It’s both. Some of it you may not know if you’re going to use it or not, but you might say, “Oh, look back. Just look back. Just take a glance behind you.” And sometimes that one little look back, you realize, “Oh. It was hard for her to leave. She looked back,” or whatever. So it’s a mixture.

What I’m trying to say is it’s a mixture of knowing at the time that it would be good to get something, and then in editing maybe it’s inadvertent that it’s just a pause in the filming, and you see a moment where Thom is looking down, or she’s stealing a look at someone, and it just was a moment that was kind of interested chill. That you weren’t directing, but it happened. And then the edit you’d say, “Oh my God. Let’s just use that. That’s great. She just stole a look over there, and you realize that she’s actually concerned about [inaudible].” So it’s absolutely a mixture.

I think only the likes of someone like Hitchcock or Kubrick could ever really say, “Okay. That was on a shot list. Every single thing that you see in my film was premeditated.”

Where their actors are marionettes being maneuvered through?

Yeah. And so in edit you find a lot of ways to fix something or enhance it that you didn’t know at the time. And similarly, at the time you try your damnedest to get some things that you realise are quiet moments that could help convey a moment that the person’s experiencing, the character on screen’s experiencing, or that it would give you the viewer a moment to just have your own thoughts circulate and register them.

Do you have an affinity for people that are making a choice not to participate in mainstream society? There are communities we see depicted during the film that are warm, and welcoming. So I wondered if you had a sort of personal affinity for some of those lifestyles or attitudes?

I do. I really do. It takes a lot to go against the grain. It takes a lot to get in touch with what you might really want or value I feel for most people. There’s a lot of dangling distractions. Not sirens, but the equivalent of sirens.

A lot of things that we’re told could guarantee our happiness or could really facilitate it in terms of something new, something better, something bigger. A bigger dwelling. The next edition of X, Y, or Z. The next model of something. A phone that was smarter than the last one. And so to figure out what it is that you might really relish or might really give a foundation to some of your day-to-day for many of us takes a lifetime to know what that is, or lots of your life. So when people identify some of those things, I’m really interested. When they make a discretion, when they make a choice, or even when it’s just dictated by survival, I’m interested in that too. Scrappy survivors, on a project prior to this one, brought me into contact with a community that inspired the community that’s depicted in Leave No Trace. It was an RV community where I filmed a documentary with a character named Stray Dog. A lot of what you see on-screen in Leave No Trace is very inspired directly – very directly – from some tableaus that I witnessed in his RV park.

A final question before we wrap-up: as a filmmaker for you personally, is it interesting to travel half way around the world to showcase an actor from the place that you’re taking your film to? From media appearances, to just how an audience responds to “that’s a New Zealander on the screen”?

Oh, totally. Very, very. As cheesy and corny as it is, I’ve been repeating this last 48 or 72 hours, cultural exchanges really work. They just really do. It was so refreshing and novel for the crew. They really responded to Thom. And there’s another filmmaker colleague that came with Thom to be of assistance to her – not her assistant, but a collegial relationship – where Thom could have just some really grounded support by an older mentor. A woman named Claire Van Beek. She’s an Aucklander. And she was present. And the crew was so happy to meet them. It was just like this new element. And not just the novelty. Many of us are attracted to someone who speaks differently than we do. Has their own accent. It perks up the ears, right?

You’re hearing your mother tongue pronounced very differently and that’s just got a novelty to it that never gets old really. It was really positive. I was just delighted that all these Oregonians were so happy to meet Claire and Thom. It’s powerful to meet people that have not shared the same home country [laughter].

I don’t want to make too much out of it. I’m just saying it was a positive thing. It was a positive infusion. And I do think that, as I said, that the fact that Thom was an outsider to where she was filming brought this beautiful quality of distillation and a nonjaded approach. Really, really, really lucky to work with a New Zealander.