Scorsese’s black comedy After Hours is one of the best films of the ’80s

Among Martin Scorsese’s filmography, After Hours has been receiving more and more praise – and now comes back to cinemas in 4K. Aaron Yap digs into why the 1985 black comedy deserves to be seen as one of Marty’s best (if not the best).

Back in 2019, I was tasked to compile a list of Top 10 Martin Scorsese movies on Flicks. I crowned his 1985 film After Hours at the top, noting it was “my most-rewatched Scorsese”. Upon publishing the list, the comments section quickly fired up, recoiling at the glaring absences of Taxi Driver, GoodFellas, et al from the selections. The decision to omit some of the greatest and most universally lauded films of Scorsese’s career was a conscious one, and the reasoning two-pronged.

The list represented a desire to showcase Scorsese’s extraordinary versatility—the often-overshadowed diversity of his output—and suggest another channel for discourse that isn’t centered on the crime/gangster cinema that he’s widely attached to. It also reflected a gradual shift in my personal relationship with Scorsese’s filmmaking.

Over time, our tastes and perspectives change. Age, experience and knowledge do the darnedest things to us. I might have once held Taxi Driver in the highest esteem above all else; there is a reason why it’s usually cited as a gateway Scorsese film for many, as opposed to say, Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore. Today, I’m reaching out and embracing After Hours more. And I don’t think I’m alone.

This odd, nutty black comedy, made away from the bureaucratic auspices of a studio system, was produced at a professional crossroads for Scorsese as a filmmaker. In 1983, plagued by budgetary issues and the pressures of external forces, the production of his passion project The Last Temptation of Christ was pulled. This, following a challenging shoot prior with The King of Comedy, and its subsequent box office failure (“Flop of the year”, Scorsese remembers Entertainment Tonight! declaring), left him in a space of spiritual and creative void.

Tim Burton was once attached to direct After Hours, and one could thank him for relinquishing the gig in order for Scorsese to step in, as its modest scale offered Scorsese an ideal opportunity to reset. With its uncredited origins in a Joe Frank monologue, the student script by Joseph Minion arrived via Mean Streets’ Amy Robinson, whose producing partner Griffin Dunne also plays the film’s protagonist Paul Hackett. The production behaved like a scrappy, bootstrapped indie. The budget was relatively low, the crew small, the shooting schedule fast and frantic. Watching the film, you can feel Scorsese rising like a phoenix from the ashes of creative collapse with a renewed sense of purpose.

It’s easy to see how Scorsese could have discovered a kindred soul of sorts in Paul Hackett, a Manhattan word processor whose escalating misadventure over the course of one night assumes the shape of a tumbling, feverish nightmare. A brief encounter with the alluring Marcy (Rosanna Arquette) at a coffee shop tempts him with the promise of romance (or otherwise), but from the moment he ventures into SoHo in a manic, surreally sped-up cab ride, Hackett is whisked into a series of awkward, darkly funny interactions with eccentric, mysterious strangers who never appear as they seem.

Not even his date with Marcy later in the night starts off as planned: instead of seeing her, he first meets her friend Kiki Bridges (Linda Fiorentino), a vampish sculpturist working on a macabre papier-mâché piece that resembles, rather ominously, Edward Munch’s “The Scream” (Hackett, the office drone that he is, mistakes it as “The Shriek”). Kiki lures him into assisting her with the sculpture, before he gives her a massage that puts her to sleep. However when Marcy does finally show up, whatever glimmer of spark shared between them extinguishes, leaving a muddy pool of mixed signals and uncomfortable revelations that eventually sends Paul fleeing into the rain-soaked streets.

After Hours encapsulates a terrifying, unrelenting energy that Scorsese has likened to “anxiety dreams”. Located somewhere between the dread-infused Kafka-esque horrors of Roman Polanski’s The Tenant (of which Minion cites an influence) and the “yuppie nightmare” cycle masterfully portrayed by Stanley Kubrick’s Eyes Wide Shut, the film exists in a heightened, fever-dream state unencumbered by narrative logic, and driven by Freudian fears.

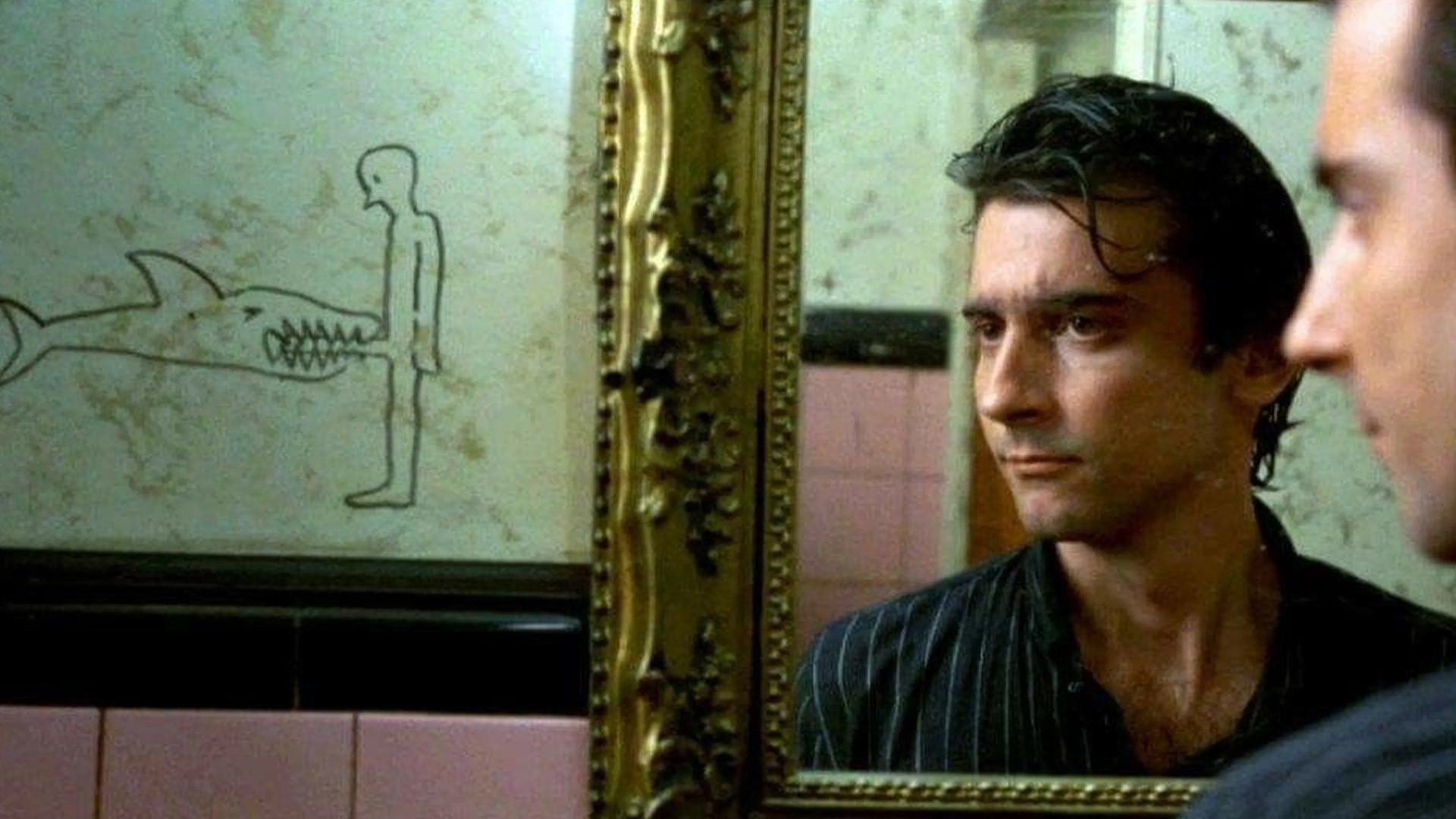

Signs of emasculation dog Paul wherever he goes, punishing his horned-up, and out-of-his-element disposition. No funnier is this exemplified visually than the scene where he sees, while at a urinal, a crudely drawn graffiti of a man whose penis is devoured by a shark. SoHo’s empty, lonely streets, where only dive bars, underground nightclubs, and a spate of burglaries show signs of life, encircle him like a suffocating maze, ushering him from one strange coincidence to the next. It’s ultimately a cosmic conspiracy of his own making, and Scorsese shoots this whole thing with a breathless kineticism that befits the thickening whirlwind of sweaty desperation and paranoia.

After Hours might be the tightest movie that Scorsese has ever made—it’s certainly the last one that has come in under 100 minutes. While its lead character haplessly spirals out of control, the filmmaking is anything but. Michael Ballhaus’ striking, resourceful cinematography, Thelma Schoonmaker’s flab-free, vice-like editorial grip, Howard Shore’s playfully jittery score: every moment of this nocturnal odyssey feels so meticulously and thoughtfully constructed, running on the fumes of liberated artistic impulses popping off every which way.

The insane dolly shot that opens the film as if to grab Paul and yank him into hell. The stunning POV shot of the key dropping from the sky carrying a seismic, portentous weight. The unnerving Hitchcockian close-ups of objects signifying everything and nothing. Even the brief flashing neon on Marcy’s face during the coffee shop scene. Not a shot wasted.

Although After Hours has enjoyed a resurgence of acclaim and recognition in recent years, it’s worth noting the film wasn’t exactly ignored in its day: Scorsese went on to pick up Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival and Independent Spirit Awards (it also won Best Feature there). With the new 4K restoration out now, it’s now no mere cinematic stop-gap, nor exercise in career resuscitation. After Hours is essential, one of the best films of the ’80s. One might even say it’s no longer underrated.