Melanie Lynskey on watching Kiwi films from half a world away

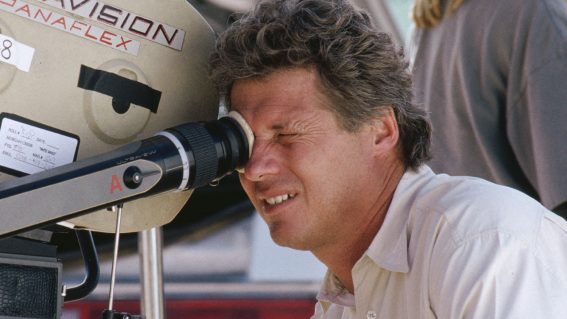

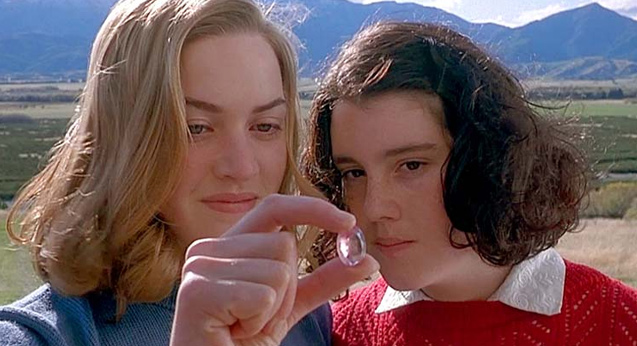

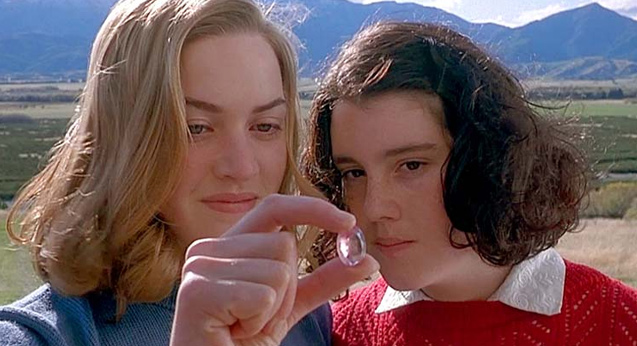

Since she debuted on screen as a 16-year-old in Peter Jackson’s Heavenly Creatures, Melanie Lynskey has forged an enviable acting career, one that’s seen her based in LA for quite some time now. From massive sitcoms to well-regarded indie films – and even a New Zealand production here and there – Lynskey’s impressed in all sorts of roles that have seen her work with some incredible directors. Last seen on the big screen here in Margaret Mahy adaptation The Changeover, Lynskey’s upcoming lead roles include indie drama Sadie and Stephen King multiverse show Castle Rock.

We spoke to Lynskey to get a sense of what it’s like to watch New Zealand films from half a world away.

FLICKS: Is there something that you watched recently that evoked a certain feeling of New Zealand?

MELANIE LYNSKEY: The thing that comes most readily to mind is Alison Maclean’s The Rehearsal, because it’s so specifically about those teenage creative years, drama school and all that stuff. It felt like such a uniquely New Zealand experience and all the kids were such New Zealand kids. I loved that movie.

Obviously, drama school’s an international experience, right? But what makes it specific to New Zealand in that film?

I haven’t been to drama school anywhere, so I can’t really speak about the experience, but from what I’ve heard from friends of mine, the multicultural aspect of New Zealand drama schools is such a beautiful and specifically New Zealand thing. It’s not really something that I think they focus on in other drama schools, necessarily.

There’s also a particular type of teacher that I think they got so exactly right and it’s hard to describe. Miranda Harcourt does this very specific thing in the movie that’s so free in a particular way. There’s just something raw about New Zealand actors and talent, and it comes from the way we’re taught to act. I really saw that so strongly in that movie.

There’s a lot of New Zealand psyche that needs to be broken down, I suppose, in drama school, because we are so utterly, horribly reserved as Kiwis. So you’re watching that happen, and also a situation where there’s not really a pathway to employment, either, necessarily.

Absolutely, there isn’t. You’re just doing it for the sheer love of it. But yeah, I think you’re right, because we are such reserved people, there’s not a natural exuberance or confidence that a lot of actors from other countries have. So you go to the deepest, most raw parts of yourself, because it’s so scary to express anything.

Are you based most of the time in Los Angeles?

Yeah.

So you’re really not in contact, day in, day out, all day, with that reserved New Zealand-type personality, then, are you?

No. I mean, I’m in contact with my siblings day in, day out – probably on a text thread – but no, not really.

So when you do watch a New Zealand film, it must be interesting to jump back into that shy, mumbly personality types that we seem to embody so well.

It is very interesting, and also the filmmakers and actors from New Zealand have these amazing achievements, and are so kind of humble about it, in this way that, I don’t know if it’s necessarily helping them, but it’s something that still feels quite beautiful to me.

Apart from Taika [laughs]. His design is a little different. But most of the time, people are like, “Oh, it wasn’t a big deal,” or, “Oh, no.”

What’s it like to see titles from New Zealand start to ripple out internationally from the other side of the world?

It’s so exciting. I went on the Film Commission website just to refresh my memory, see what I have missed, and what things I had not seen. I realised you can actually watch a lot of things on the website. Of course, I didn’t give myself enough time to do that, but it was super exciting to learn that – because a lot of things just don’t make it over here. I think because of Netflix, the world is kind of opening up in a way that’s super exciting.

Do you still get parochial New Zealand pride about seeing things do well on the world stage?

Yeah, I definitely do. I really, really do.

Is that genetic, do you think? Do we just all have that?

I don’t think it’s genetic. I think it’s just something that’s never going to leave.

I’m so proud of Taika, for instance. Everything that he does, I’m just like, “Oh my God. He’s so New Zealand.” He’s also been my friend for 20 years, but it’s incredible, and it inspires all of us to see what’s possible, I think.

Certainly, when I was growing up in the ‘80s and ‘90s, we didn’t have the Internet yet, and stuff like that. I felt so isolated and so far away from the rest of the world, and it’s just amazing to see people really having international careers.

It was such a different time growing up, wasn’t it? Even as I entered my late teens, it would be like, “Do I have enough money for the air-freighted version of the magazine, or do I have to buy the sea-freighted version of the magazine?” And that’s something that young people won’t be able to relate to today.

I know. That’s exactly my experience.

I remember when I was doing Heavenly Creatures and I got per diems, so I had this crazy amount of money – for me, as a 15-year-old – and that’s all I did. I was buying Premiere magazine and Empire magazine, and I was like, “I can get the newest version of it, and not have to buy the two-month-old one.” That’s crazy.

Are you someone that New Zealanders look up or get in touch with as they come to LA? Does that bring you into contact with people that are making their early forays into that environment, as actors or filmmakers?

That doesn’t really happen to me. I’ve been gone for so long, I’m not really part of the community [laughs]. I’ll look at Rose McIver’s Instagram, and there’ll be like, “New Zealand dinner”, and there’ll be all these New Zealanders having some fabulous dinner somewhere. And I’ll be like, “Oh, hi.” I’m just not really part of it.

Sorry to bum you out with that question!

No, I mean, I’m not entirely serious. I have some friends from New Zealand who will stay with me, or get in touch when they come over, but I think there is a community that I’m not really involved in.

This next question’s a bit difficult, because I’m asking you to look at yourself in a way, but do you think you bring a different perspective on New Zealand film because you’ve been living abroad for so long? When you mentioned how filmmakers may be quite self-effacing, for example. Is there anything you think you notice because you don’t live in New Zealand?

My biggest hurdles when I came here were feeling comfortable with compliments and praise, feeling comfortable going into a meeting, and feeling like, “Okay, I deserve to be at this meeting. I’m here because they’ve seen something I’ve done and thought it was good enough.” That was such a big thing for me to overcome.

For people that I do see coming over here, I just wish that for them. I want people to not have to go through that initial thing of being, “Oh God, am I good enough, just because of where I’m from?” which is not something that other people have. I mean, Australians don’t have that [laughs].

A psychologist would say that a negative comment is six times more powerful than a positive one to our frame of mind, but I think for a New Zealander it’s probably double that, to be honest.

Oh, for sure. I could quote every negative thing I’ve ever read about myself, but it would be impossible for me to tell you a positive one.

Have you had the chance to see those personalities play on screen while watching with an American audience, or even in an American living room, to see how they translate?

Both of my longest term partners have been American, so I’ve watched New Zealand stuff with them and seen how people respond.

I saw What We Do in the Shadows here with a big American audience and saw how people responded to Flight of the Conchords. People don’t think that it’s real, I don’t think. Flight of the Conchords, people are like, “That’s so funny, that thing that they do,” and you have to sort of explain, that’s such a New Zealand frame of mind and way of being. I mean, obviously, it’s comedy, and it’s a little heightened, but it’s so funny because it’s so real, and it’s so familiar to us.

Are there any particular things about New Zealand films – besides being, “It’s a New Zealand film,” – that makes you particularly excited about getting to see them, like any specific things that you look out for and can’t wait to see?

The main thing I can’t wait to see right now is Waru, but I don’t know how I’m going to get to see it. Films like that, which are very particular New Zealand stories, are the things I’m most excited about.

There was a screening the other night, but I had to go to a premiere and I was so bummed. It was screening just one time at a film festival, but I’m dying to see it. It’s such a great idea.

There’s definitely threads of the idea of the cinema of unease in Waru. Does that generalisation no longer apply to what New Zealand film looks like when you look at it from afar? Or is that still very much the case?

Yeah, definitely. It’s the case in some of the movies. It’s a pretty uniquely New Zealand sort of cinema experience, but I think something that New Zealand does so well is comedy, like really fun, funny comedy.

I remember I was on a flight with my ex-husband while we were still married and we both watched Second Hand Wedding [laughs]. I know it didn’t sort of set the world on fire, but we were both laughing and crying, and I was like, “This is just a charming movie.”

I haven’t seen The Breaker Upperers yet, but I read the script, and it was so funny and light – I think that’s something that New Zealand is really, really great at as well. So I think it’s a bigger spectrum than the cinema of unease.

This story is part of our month-long celebration of 40 years of NZ film. Follow all our daily coverage here.