O is for Over The Top: Stallone tries to do Rocky again…but with arm-wrestling

As we enjoy our summer, Flicks editor Steve Newall shares some of his favourite reads of the year.

In monthly column The A-to-Z of Trash, bad movie lover Eliza Janssen takes us on an alphabetically-ordered trip through the best bits of the worst films ever. This month, Sylvester Stallone goes Over The Top in a schmaltzy, sweaty combo of father-son melodrama, trucker flick and Rocky rip-off.

What sport lends itself best to cinema? With team sports like baseball or basketball, you get an in-built, quirky cast of players; this year alone, Challengers and The Iron Claw mined tennis and wrestling respectively for erotic tension and kayfabe tragedy. I have to agree with Matt Glasby, though, when he crowns boxing as the celluloid game of kings. In a Total Film article, he loosely attributed the very existence of full-length feature and sound film to the boxing movie genre, and asked: “Imagine a world without the training montage – courtesy of 1976’s Rocky et al – if you can.”

Rocky and its underdog hero—and, probably more importantly, the underdog star and creator behind Balboa—are pretty significant to the sports movie we find ourselves shaking our heads at today. Because in 1987, Sylvester Stallone would wring yet more drops of Cinderella story glory out of another, far less film-friendly athletic pursuit in Over The Top, the second Canon movie I’ve covered for this column. Stallone’s protagonist Hawk cares about only three things in this cruel ol’ world: his truck, his estranged son Michael (David Mendenhall), and his chance at becoming an arm wrestling champion, a sport which we quickly realise is not particularly titillating to watch in extended dramatic sequences.

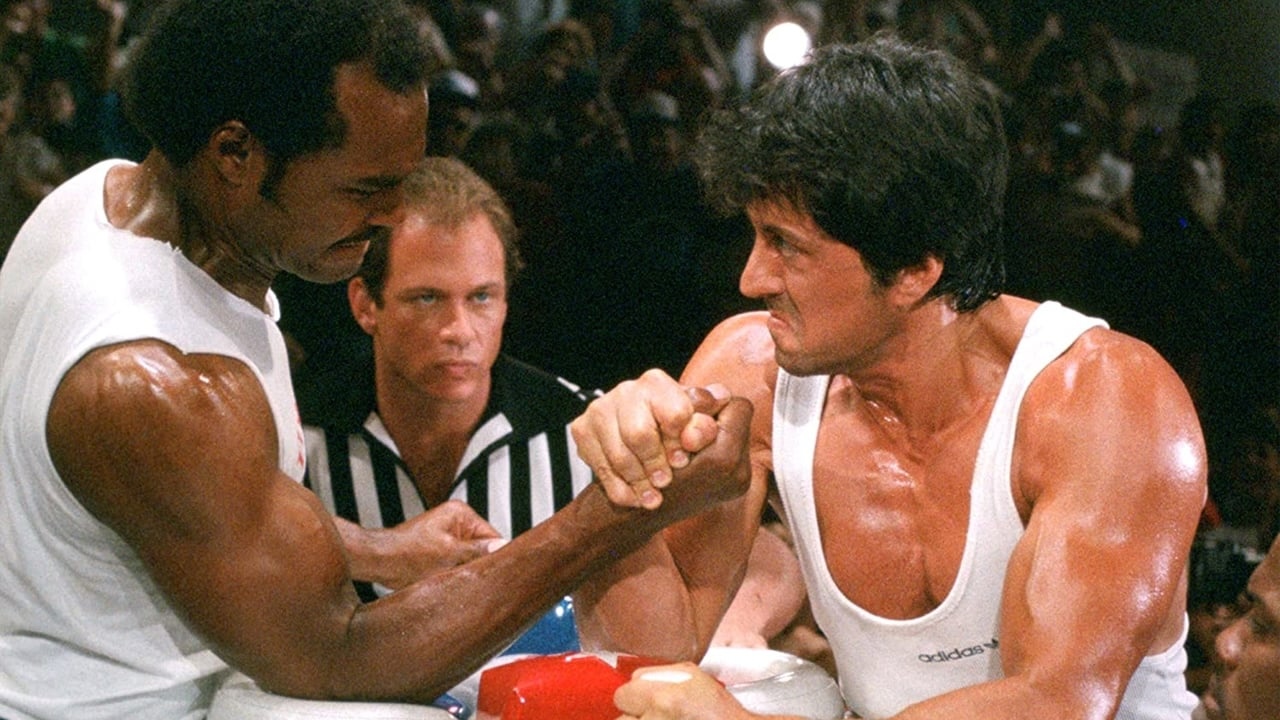

Where a boxing ring’s canvas and ropes can act as a built-in frame for action and pathos, capturing two characters at peak performance in medium shots and graceful slo-mo, arm wrestling is far more limited to extreme close-ups: of shiny biceps and straining faces. The choreography, too, basically requires actors to grunt and grind against one another, until one “gives in” and lets the other performer wham his red forearm onto the table. The title of the movie refers to Hawk’s trademark, game-changing move, of hazardously shifting his grip mid-match to go “over the top” of his opponent’s hand. It works every time, leaving each burly loser to shout that Hawk is cheating. Is this cheating? Why doesn’t every arm wrestler simply go “over the top” as soon as the whistle blows? Whatever.

Much like the single-minded, obsessive strongwoman Jackie in this year’s awesome Love Lies Bleeding, Hawk’s sights are set on a big money competition in Las Vegas. The prize money and free truck offered to the champion of this event are seemingly made for Stallone’s down-on-his-luck nobody, but one annoying little obstacle stands in his way: Michael, certainly one of the most volcanically annoying kid sidekicks you’ll ever see onscreen. Fresh outta military school, Michael is a prissy goody-two-shoes who turns his nose up at his father’s attempts to reconnect with him, at his greasy diner diet, at his blue collar wholesomeness. He bears a striking resemblance to Jojo Siwa. The pair obviously bond, road-trip style, as Hawk delivers his son to his ailing mother: Michael’s grandpa, an excellently grouchy Robert Loggia, has always disapproved of Hawk and in fact caused the guy to become a deadbeat trucker dad in the first place, scaring him away from being part of his own family. The Loggia-Stallone custody battle over Michael really isn’t helped when Hawk rams his truck through the gates of the wealthy grandpa’s mansion estate.

It’s a completely boneheaded move, but screenwriters Stirling Silliphant (an Oscar winner for In The Heat of the Night) and Stallone want us to feel that Hawk’s heart is in the right place: that, like Rocky Balboa, he’s just a man of action rather than a student of common sense. Ever since beating the odds and boasting an Oscar win for the lowest-budget Best Picture of its time, Sly has earned a reputation for overstepping on the story and screenplay credits on the films in which he appears, and working with Canon’s thrifty team (producer Yoram Globus and director/producer Menahem Golan) would’ve likely afforded him an even more indulgent degree of creative control. Left to shape this trucker-arm-wrestler-single-dad drama to fit his own underdog star persona, Stallone makes Hawk a laughably virtuous character, entirely off the hook for abandoning his wife and child and destroying his father-in-law’s property.

In one awesome scene, Hawk pimps Michael out to a trio of ratty mulleted kids at a truck stop, promising that the son he barely knows can beat any of them in an arm-wrestling match. Michael is terrified: his scummy, teenaged opponent shrieks, “If I can’t beat this kid, I’ll kill myself!” This is 100% bad parenting. But after Michael loses the first bout, Stallone is allowed to deliver a one-size-fits-all ” believe in yourself” pep talk, and that obviously turns the tables, his folksy street wisdom defying the laws of physics and fatherhood.

As for the film’s Vegas-set climax, I will applaud director Golan on how he manages to capture the glinting, flaring light that beads upon the competitor’s muscles, conjuring a heat and intensity that we know is entirely performative. Of course Stallone is gonna win, even as his opponents boast and flex in wrestling-style promos seen between each match. In Stallone’s, he mumbles under his breath about how he hopes to win the big truck, and about how he repositions his baseball cap on his head to focus his competitive mindset. We’re missing the thing that made Rocky feel so substantial—that climactic defeat, and the understanding that the journey to victory has been as fulfilling as the prize itself. If that film is a flavoursome, robust side of steak tenderised real good by heroic fists in a Philly freezer, Over The Top is a frozen patty on soggy lettuce and a mealy bun.

Still, it must be said that the movie features a Giorgio Moroder score, and soundtrack selections by Kenny Loggins, Sammy Hagar…and Frank Stallone. Hawk might not be completely respectable as a family man, but Sly is.

Originally published by Flicks on Nov 26, 2024.