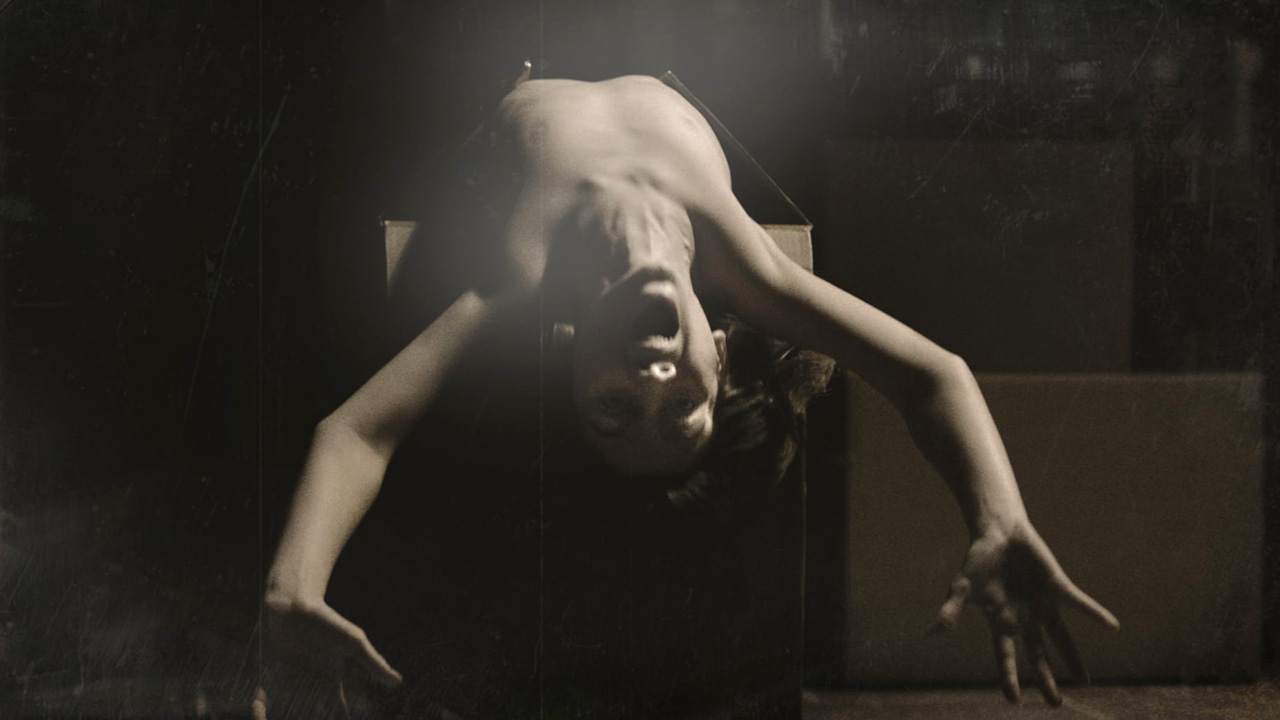

Retrospective: grim, ghastly horror Sinister brought snuff films to the suburbs

With filmmaker Scott Derrickson and co-writer C. Robert Cargill’s The Black Phone dropping its calling card in cinemas, Katie Parker looks back at the pair’s 2012 shocker Sinister.

The first image that greets us in Sinister is of a family being hanged.

Shot from a distance in grainy, stuttering 8mm, it’s perhaps one of the most upsetting opening scenes in cinema: a man, a woman, and two children, stand hooded in burlap sacks at the foot of a large tree, ropes around their necks suspended on a huge branch far above their heads. Slowly but gradually the rope is raised by some kind of pulley system—and we watch for an uncomfortably long time as they kick and struggle, before finally falling limp—and an unseen projector runs out of film.

It’s been nearly a decade since co-writers Scott Derrickson and C. Robert Cargill brought snuff films to the suburbs, and to this day I am still surprised by how nasty and dread-inducing those first few moments are.

The 2012 film, which Derrickson also directed, stars Ethan Hawke as Ellison Oswalt, a once-celebrated true-crime writer looking to revive his career with a grisly new story and another bestseller. Happily, a family has recently been murdered in mysterious and brutal fashion—and with their one surviving child still missing, he hopes he can shed light where local police could not.

And so he packs up and sets out—relocating his young family to Pennsylvania and into the exact home where the crime he’s investigating took place. (Don’t tell his wife though—she wouldn’t get it!)

Now, moving your family into a crime scene without telling them may seem unwise—but, at least initially, this turns out to be an advantageous decision. In the attic of his new abode, Ellison discovers a goldmine of apparently undiscovered evidence in the form of a box of Super 8 tapes and a miraculously functional old film projector. Movie time!

But these aren’t just any old home movies—and as Ellison makes his way through the collection he quickly finds that each reel depicts the inventive, methodical murder of family—all of which seem to have been performed at the behest of an obscure pagan deity, Bughuul.

If that opening scene feels like the stuff of nightmares, that’s because it is—and Cargill has said that the idea for the film came from a dream he had after watching 2002’s The Ring, in which he discovered a box of Super 8 films and projector in his attic. In the dream he spooled up the first film and pressed play—and, so he says, that horrible image appeared to him.

Released in the wake of a slew of found footage movies, many inspired by the enormous success of 2007’s Paranormal Activity, the idea to make a movie about someone finding footage was a good one—and nowhere is Sinister more effective than in the brief, brutal and surprisingly hardcore snuff films that Ellison watches alone in the attic after his family have gone to sleep.

It is also decidedly unsubtle—and Derrickson doesn’t leave any scares to chance. Ghostly children float around offering haunted stares and holding their fingers to their lips, Lorde style. Spooky figures in pictures twist around to grimace at the camera. Jump scares see figures quite literally jumping into the frame.

Even those so-called “kill films”, which make stunning, disturbing use of Super 8 photography, are amped up for all their worth with sudden loud sounds and bouts of ambient Norwegian death metal.

It’s an element of Sinister which, at the time, divided critics. Undeniably disquieting and deliciously dark, it’s hard not to imagine how much more effective it could have been had every spooky thing not been circled, underlined and italicised (and usually accompanied by a VERY SUDDEN LOUD NOISE).

Yet in the age of elevated (and often overthought) horror, Sinister is now something of a relic: a scary movie whose first and foremost priority is to be very, very scary.

Hawke—with whom Derrickson and Cargill recently reunited for the abduction horror The Black Phone—is another saving grace for the film, taking the sometimes flimsy plot from hackneyed to surprisingly shrewd. Ellison, whose myopic focus on his work already seems to have had a detrimental if not traumatic effect on his family, is hardly likeable—but he is also a canny stand-in for the audience itself. Why would he watch the creepy death videos he found alone in the dark attic by himself? It’s the same reason we kept going, even after being confronted with that hideous first scene—the same voyeuristic, vaguely nihilistic impulse that true crime writers rely on.

Followed up by a lacklustre sequel in 2015, Sinister is a rare horror hit that did not manage to inspire a franchise. Not for lack of trying mind you—in 2018 Jason Blum even discussed plans for a crossover with the Insidious movies (tentatively and hilariously titled ‘Insinister’) which, mysteriously, did not come to pass.

While this was no doubt a disappointment for Derrickson and Cargill, who penned the screenplay for the widely panned follow-up, it’s a boon to film’s legacy that old Bughuul didn’t get his own spin-off—and a testament to the true horror at the heart of Sinister.

Where franchises like The Conjuring, The Purge and Paranormal Activity have, for better or for worse, continued to churn out movie after movie (and in The Purge’s case a whole TV show), Sinister stands alone as a moment of pure, adrenaline based fear—a grim, ghastly cautionary tale that needs no further elaboration.