Retrospective: The King of Comedy turns a cruel mirror on those who idolise Travis Bickle

Martin Scorsese’s 11th film, The King of Comedy follows desperate, aspiring comic Rupert Pupkin (Robert De Niro) as he attempt to achieve showbiz success by stalking his idol, a late night talk-show host (Jerry Lewis). Amelia Berry revisits the 1981 film, exploring its parallels with Scorsese’s earlier Taxi Driver.

On March 30th, 1981, John Hinckley Jr. shot and wounded U.S. president Ronald Reagan in an assassination attempt inspired by Martin Scorsese’s 1976 film Taxi Driver. Hinckley saw himself in Travis Bickle, the loner vigilante protagonist portrayed by Robert De Niro. He believed that by emulating Bickle, and gaining national attention, he could get closer to teenage actress Jodie Foster, who played the child sex-worker that Bickle attempts to ‘save’. In June the same year, Scorsese and De Niro began work on a new film: The King of Comedy.

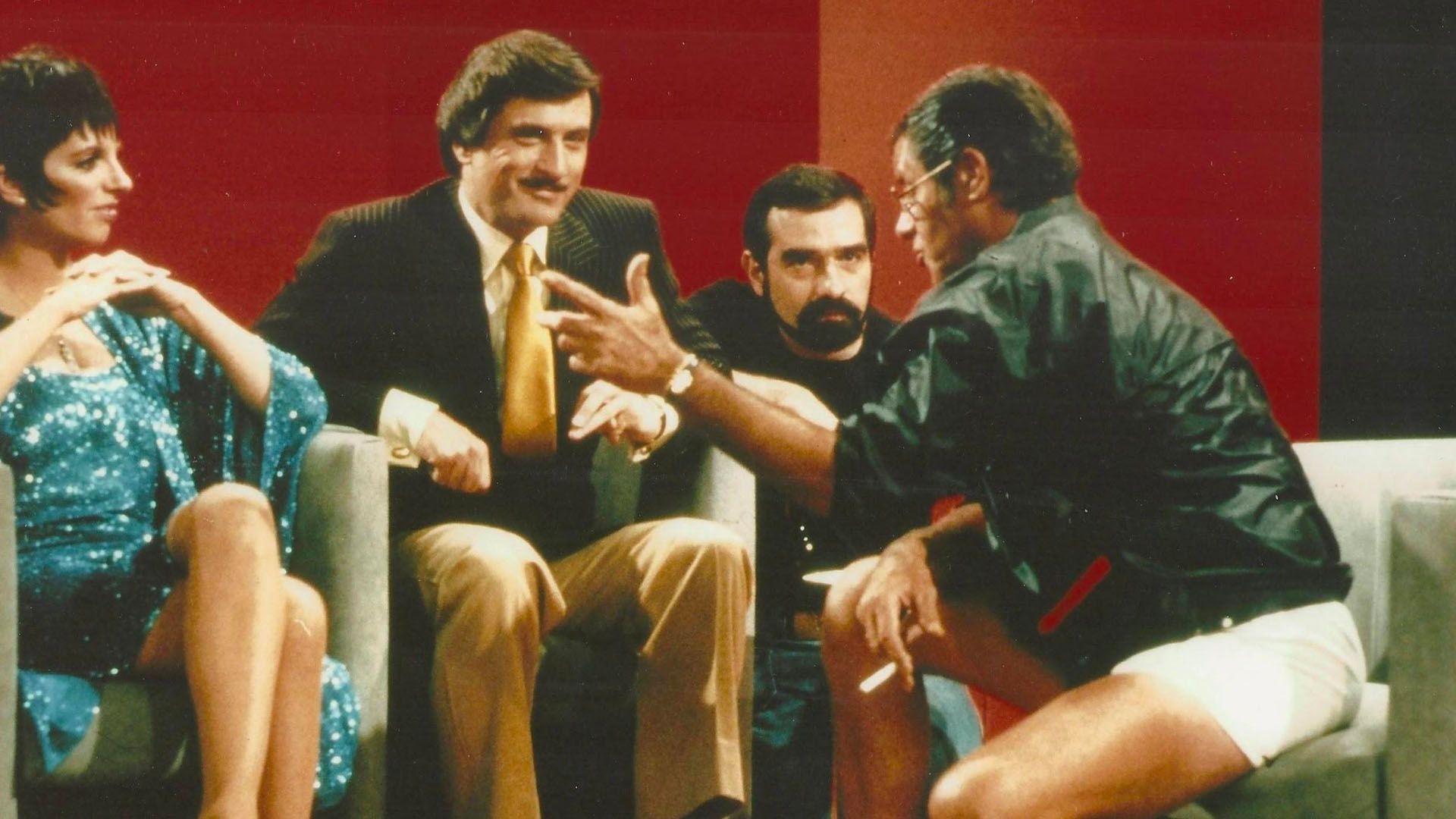

The King of Comedy is the story of Rupert Pupkin. Pupkin, played by Robert De Niro, is an autograph hunter and aspiring stand-up comedian obsessed with late night talkshow host Jerry Langford, played by Jerry Lewis. Trying to gain a guest-spot on Langford’s show, Pupkin is continually rebuffed by Langford and his staff. Meanwhile, his obsessive fantasies grow to the point where he takes his high school sweetheart (Diahnne Abbott) on a disastrous trip to Langford’s country mansion, believing that he and Langford are close friends.

Eventually, Pupkin teams up with fellow fan Masha (Sandra Bernhard) to kidnap Langford, using Langford’s life to bargain his way into a spot on TV. After the broadcast, Pupkin is arrested, but we see that soon he is granted parole and becomes an in-demand celebrity, with a popular autobiography, comedy tours, and an upcoming film.

It’s a story that runs in striking parallel to that of Taxi Driver. Both films star Robert De Niro as an antisocial obsessive, indulging in fantasies of power and ultimately seeing violence as the only option for reaching their goal. Both are stories of alienated masculinity, men who feel entitled to a certain kind of life, a certain kind of world, and feel that they have been denied what they are owed.

Both end with their protagonists becoming celebrities, lauded for their terrible acts. But where Taxi Driver’s flickering neon dynamism grants Travis Bickle an air of romance, a kind of brutal glamour, The King of Comedy turns a cruel mirror on those who idolise Bickle, revealing Rupert Pupkin as a pathetic figure, contemptible and alone.

A large part of this comes from cutting away Taxi Driver’s edgier elements. Bickle’s deep racial resentment (already toned down on-screen from Paul Schrader’s original screenplay) and his desire to protect white womanhood from sexual exploitation are easily construed as far-right dogwhistles. Without these, there can be no faux-moralistic justification for Pupkin’s actions. Bickle’s lovingly maintained arsenal of handguns is replaced with a plastic toy.

De Niro’s performance, too, marks a fascinating transformation. Where Bickle is taut, brooding, and muscular, Pupkin is puffy, simpering, and sports a goofy, lopsided moustache. While it’s an engrossing and well-studied performance, it’s also confrontingly against type for De Niro. Certainly not what Bananarama had in mind with their 1984 classic Robert De Niro’s Waiting…. The cinematography also cultivates an atmosphere of discomfort and claustrophobia with muted colours, and closed-in, static shots. It’s really no wonder that the film bombed at the box office. For audiences expecting a repeat of the sweeping grandeur of 1980’s Raging Bull, The King of Comedy must have felt like a joke at their expense.

What makes The King of Comedy so brilliant and engaging though, is that Scorsese, De Niro, and writer Paul D. Zimmerman work hard to make Rupert Pupkin more than just an unpleasant creep or a grandiose bore, but a lonely, desperate, and ultimately sympathetic character, if not in his actions, at least in his circumstances.

At a basic level, The King of Comedy inverts the familiar format of the obsessive fan film. Where classics like Play Misty for Me (1971), The Fan (1981), and (the admittedly much later, but easily most well-known) Misery (1990), treat the obsessive fan as a violent and unreasonable monster—like the villain in a slasher flick—The King of Comedy makes the fan our perspective character. Instead of a happy, successful character having their life shockingly disrupted, we get to play with a more familiar social dynamic, an exaggerated burlesque of how regular people are expected to relate to the world of celebrity: jealousy, aspiration, ambition, and desire.

Scorsese puts a surprising amount of himself into the character of Rupert Pupkin. While being obviously passionate about “show business” in a general sense, having dedicated much of his life to film preservation and advocating for the art of cinema, Scorsese also idolised 1950s comedy icon Jerry Lewis, who, along with playing Pupkin’s idol Jerry Langford, was himself nicknamed “The King of Comedy”. Rupert’s mother in the film, while never appearing on screen, is also voiced by Scorsese’s own mother, Catherine Scorsese.

Rupert Pupkin is ultimately a very familiar type of character. He’s a man with big dreams, but without the social or financial resources to fulfil them. Throughout the film he’s told to build up his routine by performing at comedy clubs, but it’s hard to picture the Rupert we see as having the competence or charm to develop the kind of relationships needed to be successful in the business of comedy, regardless of whether he’s actually funny or not. Like when Travis Bickle takes a date to a porno theatre and is shocked when she walks out, Pupkin knows what he wants but has only the most superficial and distorted understanding of how to get it.

Pupkin and Bickle’s aspirations are also totally banal, reflections of society’s most mainstream values—money, fame, the adoration and obedience of women, vague notions of justice and order—and both characters feel essentially disrespected by their position in society. Rather than working to change themselves, or change society, these men choose to exercise physical violence to achieve their ends, the only power they feel they have. In both films, this resolves in sequences that are often interpreted as fantasy, with the characters rewarded for their brutality by adoration and success.

But looking at The King of Comedy and Taxi Driver thematically, and taking into account what Scorsese and the films’ writers have said (for whatever that’s worth), these endings are meant to be taken more literally, the characters’ reality finally cohering with their deluded self-image. Because really, Rupert Pupkin and Travis Bickle getting exactly what they want cuts to the core of what these films want to say: this is what our values are building, society makes monsters out of lonely men.

Despite all this, The King of Comedy is a funny movie, pushing us to laugh and cringe at moments of Rupert Pupkin’s over-the-top ridiculousness and his grating tenacity. Through the comedy of discomfort, the film makes one conversation between Rupert and Jerry harder to sit through than Travis Bickle’s whole murder spree. By reducing Taxi Driver’s hyper-masculine mystique and heart-pounding ultra-violence to its core pompous absurdity and hollow loneliness, Scorsese realises the same social critique but with a new incisive clarity.