Revisiting the Wachowskis – some of the best, worst, and wildest films of recent decades

The Matrix Resurrections returns to an iconic filmmaking universe, and prompts Amelia Berry to revisit the career of the Wachowski sisters – the writing and directing talent who try something brilliantly and breathlessly new with every project.

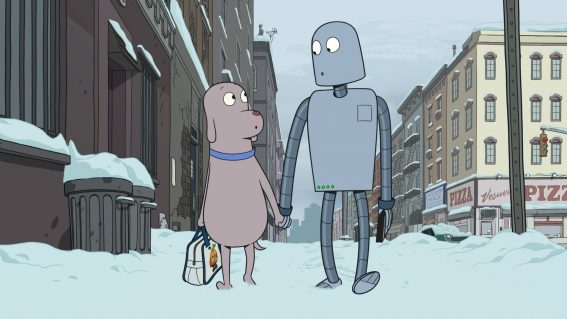

The Matrix Resurrections

In 1999, the world was asked a question: What Is The Matrix? More than twenty years later, the legacy of that question still resonates, with the imagery and ideas of The Matrix becoming unmoored from any coherent understanding of the film as a whole. Head to Twitter, and you can’t throw an NFT without hitting some literal-minded tech bro, utterly convinced that we’re living in a simulation.

Deeper down the rabbit hole, far-right internet dwellers have claimed the Alice in Wonderland imagery of the “red pill”, the concept quickly becoming so ubiquitous as to lose its radical edge, leading to even more bitter pills: the “black pill”, the “siege pill”.

With the film’s strange afterlife, and a new sequel now taking up the bandwidth at www.whatisthematrix.com, it’s easy to forget that the sisters who created The Matrix, Lana and Lilly Wachowski, are not just “those trans Matrix women”, but the writing and directing talent behind some of the best, worst, and wildest films of the last few decades.

Bound

The story, of course, doesn’t begin with The Matrix. After some unsuccessful attempts at writing films in the early 90s, the Wachowskis decided to take up directing, debuting with Bound in 1996. Starring Jennifer Tilly and Gina Gershon, Bound is a lesbian neo-noir heist thriller (under-rated genre).

Unforgettably stylish and made with a palpable precision and deliberateness, Bound is a near-perfect film. While certainly in-line with other mid-90s dark, clever crime films, The Coen Brothers never managed anything as sexy, or as cool as Bound.

These days, if you make a stylish, well-received, low-budget film, you’re tapped to direct the new Green Lantern/Ant-Man crossover reboot, but back in 1996 the Wachowskis leveraged their success towards being allowed to direct a big, self-written, sci-fi gamble: The Matrix.

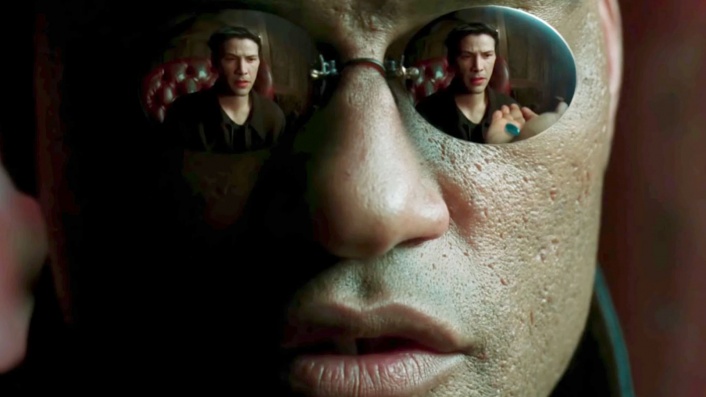

The Matrix

Much has been made in recent years of The Matrix as a trans allegory. Usually this is presented in terms of a handful of isolated moments or symbols, like the red pill representing estrogen, which was red in the 90s.This undersells the extent to which The Matrix reads to a trans audience as natively, idiomatically trans.

It’s not so much a matter of big-brained explanations, as it is of being able to understand the almost comic number of winks and references, particularly in the film’s first half-hour. To make a film about the transgender experience at all in 1999 is impressive, but the real genius of The Matrix is how it layers this with less subversive readings. Hacker style, is goth style, is queer style. Neo lurking on the internet, using pseudonyms, panicking when being “outed” by Trinity (“I thought you were a man”) is all just cool, online stuff.

On a larger scale, the film’s obvious betrayal/resurrection Christ allegory works so well because of how it interacts with the other themes. Queerness and revolutionary politics are explored through a lens of faith and love. You can’t find your ethics in a blood test, and you can’t get an MRI that tells you that you’re gay. For these things we must know ourselves, believe in their rightness, have faith.

Of course, most audiences don’t care much about trans self-discovery or anti-capitalism radicalism, but even taken as simply a clever synthesis of high-minded sci-fi, John Woo gun-play, anime, and classic kung-fu, The Matrix is sophisticated, thrilling, and tightly crafted filmmaking. Now, with the question ‘What Is The Matrix’ seemingly settled, the people wanted more, and the Wachowski sisters were happy to deliver.

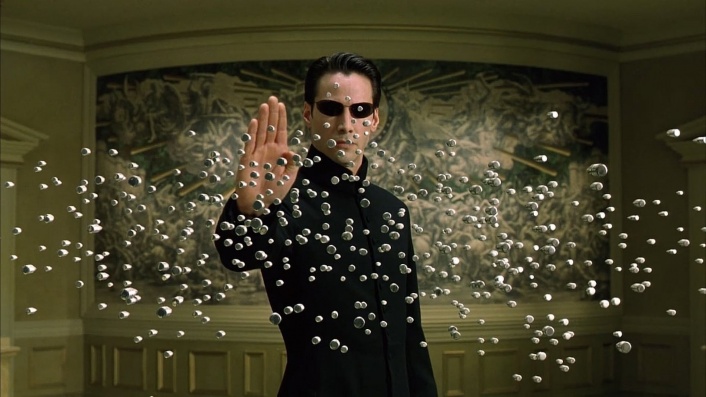

The Matrix Reloaded

The Matrix Revolutions

In retrospect, 2003 gave us maybe too much Matrix. Along with both Matrix sequels (May and November), we also got animation compilation The Animatrix, and the video game Enter The Matrix (featuring an hour’s worth of specially shot, lore-important cutscenes).

Even aside from this over-saturation, Matrix Reloaded and Matrix Revolutions were never going to live up to the original. For a start, The Matrix is a self-contained story. Reworking its concepts into a more fluid, broader lore changes the tone, the focus, and the appeal.

The Matrix sequels tackle this by becoming pulpy CGI-driven action films, drawing much more deeply from comic books and anime. They also just feel more rushed and convoluted than the original, plagued with a grandiosity that comes from extending Neo’s essentially personal story into a world-ending epic.

Watching them again in 2021, they are much better than they’re often given credit for. Not masterpieces, but rich, lovingly crafted sci-fi action oddities. More than anything, these are dense films which reward attentive rewatching, so it’s little wonder they’ve found their true audience more on hard drives and DVDs than in theatres.

Speed Racer

Taking a break to write 2005 Alan Moore adaptation V for Vendetta for friend James McTeigue, the Wachowskis would return to directing for 2008’s Speed Racer. Based on the 1960s anime and manga of the same name, Speed Racer is where the sisters would develop their current reputation for making “visually spectacular missteps”.

While there is some truth to this regarding their subsequent films, Speed Racer is increasingly acquiring a reputation as an overlooked masterpiece. In total contrast to the Matrix trilogy, Speed Racer is a bewilderingly colourful and kinetic movie, using the aesthetic and capabilities of digital film-making as a springboard to twist and pull at the grammar of cinema.

Even as it draws on a tradition of ’60s mod design, and owing a certain debt to the colour and clarity of Ma vie en rose (1996), Speed Racer feels entirely unique, revelling in its own heightened unreality. The story centres on the struggle of making art within an inherently corrupt system, working as both a metaphor for film-making itself, and is made literal in the climax of the film when Speed Racer reveals the evil of the corporate racing stooges and his driving (literally described as his art in the film) is transformed into a cathartic kaleidoscope of colour and light.

Up against Iron Man and The Dark Knight at the box office, it’s not entirely surprising that audiences chose hard-edged comic-book dramatics (owing some debt to The Matrix) over an arty children’s movie with a postmodern approach to editing. But the Wachowskis were determined that their next film, the philosophical, serious, and complex Cloud Atlas, would secure their film-making legacy.

Cloud Atlas

Cloud Atlas is the Wachowskis’ worst film. Based on a novel by David Mitchell that many considered ‘unfilmable’, Cloud Atlas largely succeeds at the ‘difficult’ elements; building rich and believable worlds, and connecting the story’s disparate storylines with the sisters’ characteristic finesse.

Instead, the Wachowskis stumble at a hurdle of their own making. Namely, the insistence on using the same actors across storylines set everywhere from 19th century New Zealand to cyberpunk future Korea.

The result is a clutch of performances squeezed through layers of accents, patois, facial prosthetics, and thinly-painted tattoos, like so much racially insensitive cheesecloth. Where it isn’t straightforwardly racist (the yellowface, the blackface… there’s more), it’s just badly done, a barrier to connecting with the characters.

This profoundly misguided attempt at “post-racial” casting, also jars with the films explicit, though shallow, anti-racist message. It’s just a mess.

Jupiter Ascending

Following Cloud Atlas, 2015 would mark the sisters’ last two projects as a duo: the campy space opera Jupiter Ascending, and their first foray into television, Sense8. While not strictly ‘good’, Jupiter Ascending is a lot of fun.

A messy, ridiculous love-letter to sci-fi cinema from Flash Gordon to Brazil, it’s largely let down by some limp performances from Mila Kunis and Channing Tatum and by a kind of overwhelming preposterousness. That being said, it’s also just so compellingly odd it’s hard not to see it developing a cult following.

Sense8

Sense8, meanwhile, follows a group of eight disparate strangers who find themselves developing a mysterious psychic connection. It’s something like Heroes or The OA, but with a lot more thematic and emotional heft.

In taking another look at Cloud Atlas’s themes of connectivity and togetherness, it does fall into a few of the same issues of clunky stereotypes and false equivalences (in one scene, calling a policeman ‘pig’ is directly paralleled with racial and homophobic slurs), but through the immediacy and chemistry of the performances we’re granted moments of catharsis and release not possible through Tom Hanks’ dreadful Cajun accent.

There’s an old saying that the fox knows many things, while the hedgehog knows one big thing. Discourse around film often privileges cinematic hedgehogs; directors like Quentin Tarantino, Wes Anderson, Christopher Nolan. These film-makers work with a singular vision, a recognisable aesthetic, repeating themes and motifs.

The Wachowskis’ best films (Bound, The Matrix, Speed Racer) hold little in common, outside of being ambitious and detailed, with a clear love and understanding of the craft. And while Wes Anderson can get by with a dull-yet-characteristic film while we wait for the next good one, it’s worth recognising the value in film-makers who try something brilliantly and breathlessly new with every project, whether it leads to an era defining classic, or something worse, something weirder, something unique.