Silo stars Common and Tim Robbins get deep on the zeitgeist and perilous state of our world

Back for its second season, the world of Silo continues to expand – and its dystopian themes resonate in our present. Common and Tim Robbins get into the heavy stuff with Steve Newall.

Ever feel like the world’s sliding into the abyss? Me too, especially in recent weeks and months. The dystopian world of Apple TV+’s Silo, in which 10,000 people live in an underground bunker beneath a ruined Earth, perhaps never seemed so likely.

Now back for its second season, Silo continues to build on the notion that everything’s not quite as it seems. For those that aren’t up to date with season one, I have two things to say: the first is “bloody watch it already”, and the second is that we will not be getting into any major spoilers for season one or season two here—the revelations of Silo are best experienced firsthand.

In broad terms, season two is largely divided into two separate storylines. One sees Juliette (Rebecca Ferguson) continue her dogged pursuit to understand the truth of their predicament, a quest that will bring her into contact with new cast members (Steve Zahn bringing a welcome vitality to proceedings). But in doing so, she’ll also inadvertently endanger every inhabitant of her below-ground sanctuary (or is it a prison?). Juliette’s pursuit of truth carries a dangerous whiff of folk hero or martyr, and Silo is very much interested in exploring how this can prove contagious in unexpected, survival-threatening ways.

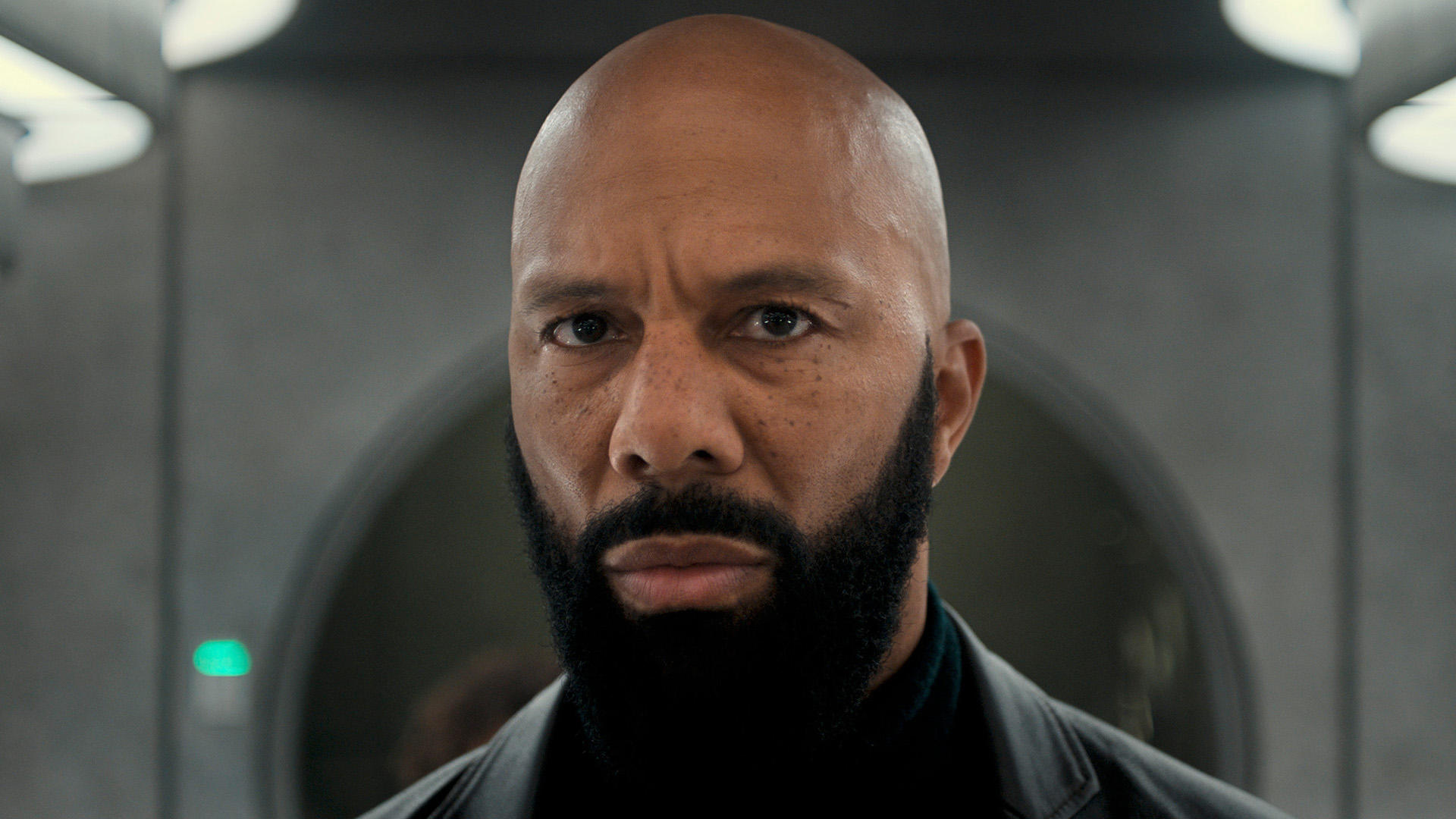

These are challenges also faced by the Silo’s Mayor, Bernard Holland (Tim Robbins), and head of security Robert Sims (Common). How they wield and maintain power in both delicate and indelicate ways is a fascinating thread running through the new batch of episodes, with life in the Silo finely-tuned to function across the generations—and now at increasing risk of coming apart. The relationship between Holland and Sims itself is not immune to competition over who gets to make the big calls.

Fortunately, spending time chatting to Tim Robbins and Common proved a more enjoyable experience than what you might imagine being stuck in a vast underground bunker with their characters would be… though as you’d expect, talking about the themes of their show—and the state of our own world—led us into some heavy territory.

Not that our convo started that way. The actors’ friendly chemistry was evident, a world away from their ever-serious onscreen selves. “Working with Tim has been inspiring for me,” Common says of his co-star. “It’s been nothing but joy, even though it is, you know, we are dealing with…”

“We’re having fun in a dystopia,” Robbins interjects.

“Yeah that’s it, ” Common chuckles. “You gotta make the best of it. That’s what we do.”

One of the things that I keep coming back to with Silo is how the inhabitants have needed to work cooperatively for generations, due to the threat and imminent peril literally hanging over their heads. It’s distinct from our society in a way that will be familiar to viewers of documentarian Adam Curtis’s Can’t Get You Out of My Head: An Emotional History of the Modern World.

There, Curtis highlights the fracturing of collective identities, painting our modern world as a product of systems of power and influence which use the concept of individualism to prevent us from embracing a sense of communal and social good, forming collective aspirations, or enacting meaningful change to the systems that control us. I put it to the actors that struggling for a common purpose is perhaps something we need more of in our day-to-day existence—a shared ethos of some kind.

“I would say yes to that question,” says Common, “Because for me, like growing up, I can remember things being more zeitgeist. Like, if everybody was into it, a lot of people would be into it. We had a common thread of things to share and talk about, or just common interests. And I feel like now in today’s world, so many people are focused on so many different things, that commonality is not as present, the expression of it is not present—even the idea of trying to find that commonality.”

“One good example, I can remember when music used to be released on Tuesdays. Everybody knew that this new album was coming out, and we would all check it out, and we could talk about it and that’s how it was for a television show too. The show came on Thursday, we would talk about it the next day at school. And now it’s like kids are into so many different things, I feel like people just don’t have that commonality.”

“You think that’s intentional?” asks Robbins, taking on the mantle of interviewer.

“Yeah, I do” his co-star replies.

Robbins picks up the thread: “You just cut back 25 years, you know, we’ve lost bookstores, we’ve lost record stores, we’ve lost even getting a CD. A common ground, you know, a place where people can go and have that kind of experience. A new album comes out, and it’s an exciting thing, and people talk about it. A place where you can go and say, Hey, Mr. Person that works in the record store or the video store, “what’s good? What should I check out?” Right? We don’t have that anymore.”

“Now, it’s an algorithm that’s suggested to you by a website. And that requires an arbiter, someone to make that cultural decision for you, rather than a conversation you would have in a record store or a video rental place. You know, personally, I’m concerned by that. I think it’s intentional. I think that the more meeting grounds, the more places that we used to have, we could gather with people that might not share the same politics as us, but might share a similar interest, like music. The more those things are eliminated, the worse it is for society. And you’re not going to get that from online groups. It’s just not the same thing.”

“Man, you just cracked that,” says a reflective Common. “For me, you just cracked the whole code of some of the disassociation or the divide. It hit me as you were saying it.”

“I don’t think it’s accidental,” reiterates Robbins. “I think that kind of stuff is what people in power fear the most—communities gathering to share a common emotion, or a common love for music or art or music or films.”

I point out how we see in season two of Silo how humanity seems destined to rise against those constraints. As much as it can be allowed to, at any rate, because the Silo is already a literalised version of what these two have been talking about. With their characters challenged by these concepts, I ask them how you can push against it.

“One of the ways that people push against it is culture,” replies Robbins: “A shared language of art or music or a story. It’s no accident that there is not a lot of culture in the Silo. It’s too dangerous. It’s why, you know, historically, the fool was the king’s truth-teller. It was the satirist that told the truth. If you can make people laugh at people in power, they’re done.”

So much of what Robbins is saying clearly resonates with Common: “I know so many things were communicated through song, through art, through culture, so many philosophies. Shoot, in many ways, when going back to slavery in America, some of our people who were enslaved communicated through songs, and the master didn’t even know what they were saying. So art being suppressed is definitely present in the Silo.”

At the time we’re chatting about these heavy matters, there’s a massive elephant in the room. The US Presidential election hadn’t taken place yet, and the outcome was still anyone’s guess. While it was opening a whole Pandora’s box of conversation as our time was running out, I still had to ask about what it was like for each of them to balance the dystopian fictitious world of the show with what they were living with day-to-day.

“I think it’s approaching,” says Robbins about the potential for dystopia, before welcomely adding: “I think we can fight it off. I think individual liberty will fight it off. Individual freedom.”

“I think the most dangerous thing we have facing us is a worldwide movement towards less autonomy for the individual and more compliance with the state,” he continues. “And so if anyone has any fear of it, you should look at what a dystopian society is right now. Which is, you know, in China—if you go against the state, you will lose your access to your bank account. That could happen in the world right now. And I think that’s the biggest enemy right now that we all have to be aware of.”

Common reflects on the question from a different perspective. “Even going back to Silo, I think one of the most important things when I look at leaders, is the humanity of a leader,” he says. “So for me, I’m not a big ‘I’m with this political party’ person. That’s not my thing. And just because you’re with a certain political party, I don’t feel like you’re the opposition.”

“For me, it’s about looking at human beings and saying, is this person going to be at least a considerate leader and a compassionate leader? That’s what we want,” Common concludes: “Not just for America, but the world.”

I’ll leave you to draw your own conclusions about whether the past weeks have delivered that outcome—just as you can discover the fascinating world of Silo for yourself. And maybe go find that book or record store, if you’ve got one nearby…

INTERVIEW EDITED FOR LENGTH AND CLARITY