‘Swagger of Thieves’ Julian Boshier on his Head Like a Hole Doco

Notorious NZ band Head Like a Hole get the documentary treatment in Julian Boshier’s Swagger of Thieves, which has its world premiere at Auckland’s Civic as part of the NZ International Film Festival on August 3rd.

Boshier sat down with Flicks to talk about his decade-long project, capturing the highs and lows of the band, their sometimes magnetically attractive (and other times repulsive) personalities, rock n roll friendship, families, and yeah, drugs.

Has the band seen the film yet?

The present band lineup saw a screener approximately two months ago, and from that version we’ve made it shorter and tighter and etc. But the screener version they saw, they were blown away by, all of them, Tamzin [Beazley – married to Head Like a Hole’s singer Booga] especially. She just could not believe it. I don’t think she really fully understood what I was doing. The boys have got a bit of experience when it comes to camera, all the music videos I’ve done over the years, and they sort of know how it works. But Tamzin really didn’t know what I was doing, so she was quite astonished at the narrative for the sort of story that’s been carved out. That’s why she went and wrote that article for Simon Sweetman’s blog.

Going back to when you first started filming the band, was it with something like this in mind or was it just picking up bits of footage at that point in time.

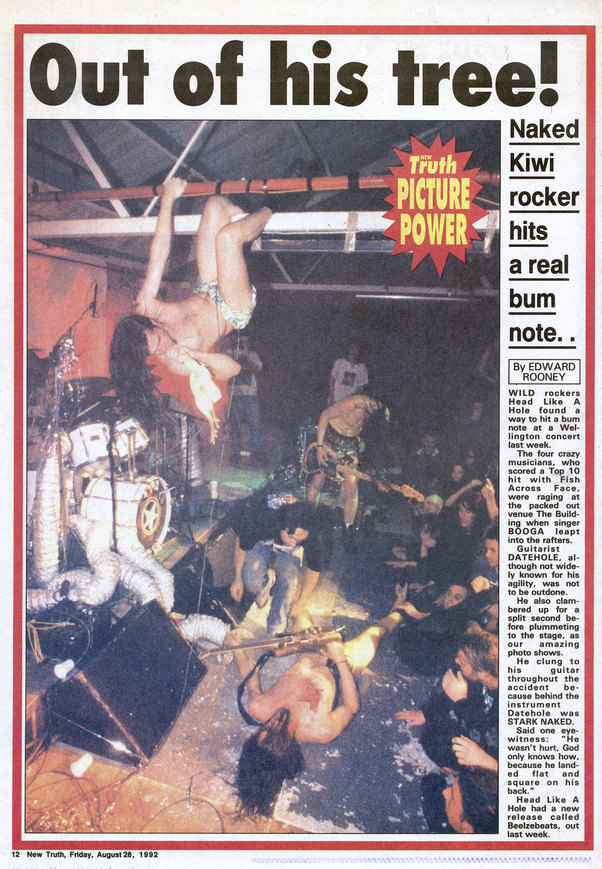

It was always, for me, a great opportunity because somehow, uncannily, I have developed quite a personal relationship with, one of the most exciting bands in this country. Not only from the point of view of their music, but also from the point of view of their character, and their personality, and their drug taking, and their history. I’ve always liked those dangerous rock’n’roll bands, the danger. You go and see someone in concert, you don’t quite know what is going to happen.

Were there specific things that drew you to the band? Certain elements of their personality?

I’ve been in the TV industry for about 25 years now, so I’ve worked on a lot of documentaries. Nothing serious, but a few documentaries. I shot the documentary about Charlotte Dawson. I was a camera assistant on a documentary about South Auckland’s serial rapist. And I’ve shot a lot of reality TV over the years. Not recently, because I haven’t done any of that stuff for ten years, but when I was younger. So I sort of had a fair understanding of what it takes. And for me, it’s like you’ve got to have people that ooze character. Or even if they don’t ooze character, they’ve still got to have some degree of character. Even if it’s boring, or nonchalant, or there’s nothing there, they’ve got to have something.

And so, what’s the story? Because I don’t think you can make a documentary unless it’s got a story. It’s got to have a story. If you made a documentary about Mick Jagger, or I don’t know, Donald Trump or something, it’s still got to have a story, despite having a big celebrity attached to it.

So, I think that Head Like a Hole, for me, fit the criteria. And it also helps that everybody knows them in this country. Everyone knows Head Like a Hole. It just sort of rolls off the tongue, and it has done for the last 25 years, really. Everyone’s got a story about seeing Head Like a Hole.

For me, it was the Powerstation shows. Seeing a thousand people crammed into that room.

And if you went to university, they constantly did the orientation tours. So they’re kind of world famous in New Zealand, aren’t they, Head Like a Hole? Yeah. So that was the appeal. And also, just knowing that somehow I could carve out a story.

With a band that’s had the lifespan that they’ve had, often a film like this would be about picking up the pieces of something that’s completely fallen apart, or it will be about, “Will they hold it together for their comeback show?” And this is a bit more complex because that stuff’s kind of already in motion, a lot of it. As the viewer, it feels less about, “Can they handle a show?” as it does about actually getting a bit of insight, to some extent, as to what they were like as a functioning band.

Yeah. I mean, I think that comes down to the access I had. I think the camera did disappear, actually. And those guys just had no qualms about speaking their mind when the camera was there rolling. But that’s because I’ve known them for 20 years, and I’ve done a few of their music videos. And that’s just, “Oh, it’s just him with his bloody camera. He’s always there with his camera.” Just that kind of thing, I think. Yeah, it is interesting that they’re still a working band after such a long time. And that was the approach that I reckon was always there from the outset. Go back in time and do the kind of traditional history of the band, and where they met, and all of that. But I didn’t want to do too much of that because I like the contemporary stuff.

Well, for the viewer, it’s great that we don’t get a recap for a little while into the film, because that’s not needed up front.

I think there was some real basics that I always had in mind, like peeling back the onion of a story and not revealing too much too soon. But that took a year and a half to work out in the edit suite.

What’s the sum total amount of footage that you had to work with with this film? And how much ended up as “This is good stuff. Shit. How do I get it down?”

Well, I overshot. I definitely overshot for, say, a two-hour project, and so the very difficult part was discarding. Our original cut was six hours. And sometimes it’s better not to overshoot, but I did because with these guys – if you’re not rolling, something’s going to happen, somebody’s going to say something, and if you’re not rolling, then you’re going to miss it. So it’s really, really tricky. So the best policy is just to roll, and just know when to turn the camera off because it’s not going to go anywhere, or keep going. And it’s always a risk. You’re going, “Oh, my battery’s going flat, I’m going to run out of disk space. Am I going to get it?” And then, boom, Booga says something to Nigel, and it’s just like, “Oh my God, I got it. Fantastic.” That will make it into the film. I know that for a fact.

Like saying the perfect line?

Yeah, the perfect line. A bit of body language, a look or something. And I always knew that the heart of the story was going to be really about Nigel Regan and Booga Beazley, because Head Like a Hole is essentially those two guys. That’s the genesis.

This love affair, professional/personal relationship story.

Well, they are married to each other, and a lot of the time that marriage is tense. Fractious [laughs].

We see how the two control band dynamics and operate as a one-two partnership within the band when they’re dealing with the other members. That they’ve got defined roles, and play within those roles, to some extent. Is that a sense you get when you’re filming them?

The sense you get is that Booga is the boss. He is definitely the boss. Not musically, but he’s the boss of what’s going to happen, what direction they’re going to go in, who’s going to join the band, who’s leaving the band. And Nigel is the musical director. Nigel usually is the guy writing the music, sometimes writing the lyrics. But Booga’s influence over the music is massive. If he goes, “We’re going to do an album, Blood Will Out, and the inspiration’s going to be the stuff we’ve always liked, Black Sabbath metal,” then that’s the way it’s going to be. And if Nigel’s thinking, “Well, I’d rather do an experimental album that’s not like that,” then Booga’s is going to win the argument.

And some would say that the direction of Head Like a Hole hasn’t been sort of on track for the last couple of albums. There’s differing directions Nigel and Booga want to go in, but they invariably are a unit, even though within that unit there are two different opinions a lot of a time. The other band members, I hate to say this, but my feeling is they’re dispensable. As Nigel Regan says in the film, “If it’s me, Booga, and your grandmother, it’s Head Like a Hole.”

I don’t know what the other band members feel when they see that scene. Andrew Durno has seen that scene. He didn’t really comment about it, but I think those guys know that Head Like a Hole is those two guys and that’s just the way it is.

One of the things that I was thinking about while watching the film was the role that the camera played for both Nigels when they weren’t working with the band. If you’re cleaning windows, if you’re sitting in your flat writing songs and comparing yourself to your peers from the past… “Where did we go wrong? Why are things like this? I’m fucked off about it.” Does the camera play a role for them in actually being able to express those grievances?

Absolutely. I think the camera for these guys was very cathartic. Actually, the first time I interviewed Andrew Durno, we did a two-hour interview, and afterwards I was packing up, and he said, “Oh my God, it’s incredible. I feel like I’ve just been to see the psychiatrist [sic]. This weight has lifted off my shoulder. I have just spilled my guts on the floor like I’ve never done before.” And he felt really good about it. He felt kind of cleansed. He said his piece. He had a lot to say and most of it wasn’t very complimenting of Booga or Nigel Regan. So that was that. I think, yeah, I was a sounding board and the camera was a vehicle for them to offload. And it may surprise you, but despite them sort of being best friends, they don’t have a very honest relationship with each other. It’s not very transparent.

That comes across very strongly in the film, I think. Especially, knowing how bands function, how these friendships function.

There’s a lot of holding back. At the forefront, there’s an understanding that if you say the wrong thing to the wrong person that’s going to create two or three weeks of silence or non-communication.

It feels a little bit like that it’s handing a weapon over to someone else. “Look, I’m just giving you a loaded gun with this unguarded comment.” And as we see, those unguarded comments have real ramifications for the band.

Yeah, that’s right [laughs]. I think for all of them, the camera and the process of making the film was actually really, really refreshing for them. They could offload to me and I wasn’t going to pass judgement or comment upon what they were saying. Nigel could not do that to Booga, and Booga could not do that with Nigel. So I think they were cleansed.

Hey, speaking of cleansed, let’s talk about drugs. Because obviously they play a really big part in the story of the band. And I don’t think we see many moments in the film where they result in a positive, creative outcome. I don’t think I’ve ever seen band members take drugs in such an unglamourous way on screen before. It’s usually implied. People talk about their problems in retrospect. Did you have a particular view in mind on how you were going to handle weaving that into the film?

Right from the day dot, when we were discussing making this documentary, right from the beginning we all agreed that it was going to be warts and all. Actually, Nigel Regan said, “I’m into it, but it’s got to be warts and all.” Nigel Regan’s watched a lot of documentaries. He’s read a lot of books. He’s incredibly well-read, Nigel Regan. He knows a lot about film and documentaries, and I think he realised that, “This is us. This is Head Like a Hole. We do have a certain quality about us, so we’d better make this documentary warts and all, which means it’ll be good.” And so we were all on the same page. It had to be. Because you can’t make a documentary about these guys and not show the bad stuff.

I mean, A, everyone wants to see the bad stuff; and B, in this band, there is a lot of bad stuff; and C, it’s not going to be a good representation of Head Like a Hole if that stuff is not at the forefront. It had to be there. So that scene that you’re referring to, that’s when I was on tour with filming the Comfortably Shagged music video. And the Comfortably Shagged music video was just shooting stuff on the road. There was no clear plan of what the video was going to be, I was kind of shooting it in the documentary style. So the way that’s ended up in the film [the drug use] is incredibly fortuitous, because a couple of little shots of that ended up in the music video. Just the shots with the fits in their mouths, but nothing that graphic.

I was very lucky because that was the last tour before they broke up for the 10 years, when everybody just couldn’t handle it anymore. And I remember Nigel and Booga were in my car with all of the camera gear and my camera assistant, and we were just driving from H-house to H-house. Through each little town, we were driving around, scoring drugs [laughs]. It was a real eye-opener for me. And inserting that into the film, it had to be done, and Nigel and Booga have absolutely no issues with it.

Actually, they instructed me to make this film as bad as I possibly could. Because I think they enjoy the notoriety. Or they did enjoy the notoriety. I’m not sure about now.

I think it’s remarked on in the film. The notoriety ends up propelling itself along, because the audience it brings to the shows perpetuates the behaviour, which perpetuates the fuck ups, which perpetuates the notoriety, which perpetuates the people coming to the shows…

I think in some ways, the Head Like a Hole image probably is a little bit orchestrated for effect, like most bands do orchestrate their image. I think these guys have done that. But in saying that, when you’re with them, it is a rock and roll circus [laughs]. It is incredible how chaotic their entire career has been. They’ve been through so many managers. They’ve really been, in the last few years, rejected and shunned by the music industry. And I think that’s because of their behaviour and their reputation. No one wants to deal with drug addicts. They have cleaned up. They’ve really cleaned up since the old days. But still, I think that reputation still exists.

Did you shoot some of that sort of stuff, like ex-managers, record companies, or did you just decide to exclude that?

Well, as I was saying earlier, I wanted to have a fresh approach. Yes, in the early days I was thinking it would be quite good to get a perspective from industry people. And a lot of documentaries have the perspective from other famous celebrities.

“We’ve gotta get Dave Grohl in this”.

Dave Grohl. Dave Grohl is in every single [laughs] fricking music documentary I’ve ever seen. So that idea was there. But on the other hand, as we got editing, we were sort of thinking, “Well, let’s just let them tell their own story. This is their world.” I mean, I could have done a number of things but I guess you got to draw the line somewhere.

If I had interviewed industry people, I know exactly what they would have said. It’s pretty obvious. They would have said something like, “Those guys had amazing potential. They could have taken on the world but they are drug addicts, and no one is interested in working with drug addicts.” So it’s almost like I didn’t need to go and film them because I think the audience will gather that.

Before we wrap up, is there anything that we haven’t touched on that you think is good for people to know about the film?

Well, I think something to know about the film is the conditions the film were made under, as in there is no funding attached to this film, which means there have been no sort of conditions. There’s been no deadline.

Which sounds like a huge challenge in itself.

If the film had been made under different circumstances, like funding from the Film Commission and a deadline, etc., it would have been a different film. I think the great thing about this film is it has not been censored in any way. If people think there’s a certain quality to the film, or if certain people really resonate with the end result, I think that could be because it had no time limit, no deadline, no external funding, and it’s been going for a long time. And the editing has also been going for a long time as well.

So from day dot, that was the decision that I made to make it in this way, so the end result would have a certain kind of uniqueness to the film. And the intention was to make something with a fresh approach. And I also think that with this band, this unique approach had to be taken because it’s Head Like a Hole.

‘Swagger of Thieves’ plays at the NZ International Film Festival

Official Head Like a Hole website | Extensive Audioculture profile