The Case For 3D (or why Walter Murch could be wrong)

In early January of this year, esteemed film critic (and now blogger) Roger Ebert posted this brief letter to him, written by Academy-Award winning editor and sound designer Walter Murch, about Why 3D Does Not Work (and never will according to Ebert). As far as ‘The Ebe’ was concerned, this was case-closed as Murch pointed out some of the aspects of stereoscopic films which are at odds with basic human biology and how our vision actually works.

And to Murch’s credit…he isn’t wrong. There is nothing factually incorrect about his conclusions. But in the spirit of the technological development of cinema, a medium that stimulates our minds through the engagement of our visual cortex, I think that Murch is being uncharacteristically short-sighted.

I believe that 3D is the next horizon for recorded visual entertainment — film, television, music videos, advertising, the works — though whether it’s this current fad for the concept that will take off or whether it will die and be reborn in some future format is difficult to say. And I think Murch is being rather unfair and doing a disservice to the pioneers who have, in the past, put up with similar criticisms to bring us the staples that we enjoy in our modern cinema experience: sound, color, editing and visual effects.

To understand my position, let’s take a quick stroll through history. It’s not a short journey, but I think you’ll find it interesting and I’ve peppered it with lots of images and videos to keep you awake. So, let’s hop in our virtual time machine and go back to look at what is regarded as the world’s first colour feature – The Black Pirate (1926) starring Douglas Fairbanks Sr – and the first successful ‘talkie’ film – The Jazz Singer (1927) starring vaudeville sensation Al Jolson.

Anybody who is a film buff would tell you that these two films were instrumental in the – very rapid – development of color and sound films and paved the way for those early classic films which defined the era and the shape of things to come…films like King Kong, The Wizard of Oz, Frankenstein and Gone With The Wind.

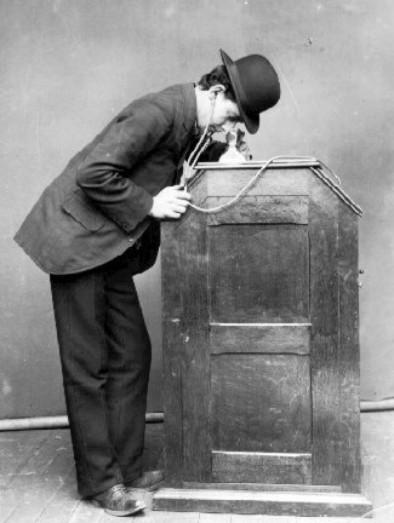

But The Jazz Singer and The Black Pirate were NOT the first talking or color films. They were merely the first ‘commercially successful’ ones and this fact gives much insight to how people’s memories and nostalgia for films clouds over the actual reality. The first successful demonstration of synchronized sound and moving image (i.e. the first ever piece of ‘talking’ footage) was created by inventors Thomas Edison and Eudweard Muybridge in 1895. Yes that’s over 32 years before the The Jazz Singer and the process by which this technological marvel was realized was quite different from how it is done today and was only viewable by a single person at a time through a device known as a Kinetophone.

You think 3D glasses are uncomfortable?

In the three decades that followed, various unsuccessful attempts – both experimental and commercial – were made at synchronizing sound with pictures; each making significant technological progress (e.g. the 1919 invention of printing sound on film alongside the picture information), but none managed to convince the film industry nor the public that sound had any place in the great and marvelous story-telling magic and tradition that was silent cinema. People thought that adding sound to movies was ‘vulgar’ and ‘gimmicky’, that it would make films ‘irrelevant’ and ‘no different from a stageplay’. These attitudes were so prevalent they were even spoofed in the 1952 Gene Kelly musical about the transition from the silent-to-talking-film-era: Singing In The Rain. Not until the release of The Jazz Singer did audiences realize the shocking implications and creative power of merging sound and picture together and they paid again and again for the experience of being wowed by a glimpse of the future…perhaps not unlike the recent experiences we’ve had with films like Jurassic Park or AVATAR.

Thirty years of development, failures and outlandish ideas before a technology was capable of being accepted by cinema audiences and industries alike as the real future of the film…and that technology was (let’s face it) still in it’s infancy. While creators of The Jazz Singer took great pains to ensure that the audio presentation was as immaculate as 1927 technology could allow, a rash of talkies which sprung up over the next decade didn’t fair so well: many a film’s soundtrack was scratchy, low-fidelity, filled with hiss, pops, difficult to hear dialogue and overpowering music. It would take almost another 15 years for films (and sound technology) to allow the majority of movies to have crystal clear (albeit still mono) sound.

And what about the modern sound that we enjoy in our movies today? 5.1 or 7.1 mixes with powerful woofers and crystal clear treble, digitally recorded and reproduced with such accuracy as to immerse us completely in an environment? Well, the first such major feature film to have digital sound was 1992’s Batman Returns and even that was still a stereo mix for most cinemas. The gradual implementation of digital 5.1 sound into cinemas was an exercise that happened only in the last decade, drawing a development arc from the Kinetophone to the multiplex that spans almost 100 years. A whole century just to get to the point where we can create sound in the theaters that mimics sound in the real world.

And what about the wonderful world of colour?

Well the earliest use of color film for commercial purposes (i.e. in a narrative film) dates as far back as 1908 and prior to that, there were a slew of 19th Century films that were hand-colored with dyes and inks, frame-by-frame, as it is done in 2D animation (known as the Pathechrome process). But 1908 the first natural colour-photography system was developed, entitled as Kinemacolor, and the first full-length colour film was released in 1909 – a whopping six-hour documentary With Our King & Queen Through India which covered the coronation of King George V and his visit to Delhi. Fourteen years after the first usage of natural colour photography, another breakthrough was made by an inventor named Herbert Kalmus who invented the now famous Technicolor Process and released his first feature: The Toll & The Sea (1922) shot in limited two-strip Technicolor.

Although the film was a financial failure, Kalmus’ technology attracted the attention of many filmmakers and the same technology was used to film Douglas Fairbanks Snr’s smash hit The Black Pirate only 4 years later. Of course this is new and infant technology in cinema that we’re talking about here…so naturally things don’t go as smoothly as that. Kalmus’s Technicolor Process involved shooting scenes on two strips of single-color film simultaneously and then gluing the strips together to create the limited-colour image. This meant that the film running through any movie-house’s projector was TWICE as thick as normal…so it wasn’t surprising that the film would often get stuck, catch on fire, warp, distort, become unstuck as the glue melted with the hot light and sometimes explode spectacularly and make life very interesting for the the projectionist on duty that night. Although The Black Pirate’s premiere screenings went without a hitch, most other screenings ran poorly and the acceptance of colour suffered a significant setback — again branded as an ‘expensive gimmick’ alongside talking pictures.

It wasn’t until another 6 years later that colour-film got its next big break in the form of a man named Walt Disney.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VTuIb7BIFqk

Disney’s animated Silly Symphonies branded short Flowers & Trees (1932) was to be the testing ground for Kalmus’ new 3-strip Technicolour process which not only reprinted the colour image onto a single-strip of projector-friendly film, but was the first time in human history that audiences saw every color of the spectrum in a moving picture image. Flowers & Trees was a smash hit, winning the first ever Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film and audiences flocked to see the latest technological marvel: full, moving, colour images.

Two years later we had the world’s first full-length, feature film shot in full colour (using the 3-strip Technicolor process). Becky Sharp (1935) was an experimental film produced by studios to gauge the power of colour, followed in 1936 by Trail Of The Lonesome Pine, the first full colour film to be shot outdoors. Both films were marred by their experimental aspects and – as a result – were not hits in the box office, but of course this changed completely in 1937 when Walt Disney flexed his Technicolour muscles with the release of the world’s first full-length, full-colour, animated film Snow White & The Seven Dwarves.

If there is any film that you could draw a direct parallel to James Cameron’s AVATAR and what it did for 3D, then Disney’s Snow White would be it. Apart from being a box-office and critical sensation and kick-starting an industry and audience rush on full colour feature films and animated films, Snow White intrenched a notion into people’s minds of what the future of cinema may hold for sound, color and animation in the same way that AVATAR did for 3D and for the evolution of visual effects (whether or not you enjoyed the film on a personal level and, let’s just be honest for a second, Snow White is also very simplistic and conventional story — something noted by critics even back in 1937).

And yet, Snow White was still technology in its infancy. Even today, on DVD, it can be hard to understand the squeaky, low-fidelity recorded dialogue and audio from the film and the color sequences were both deliberately muted and limited by the dyes and processes of the time. And while colour feature films suddenly began cropping up all over the place after Disney’s megahit, the process still had tremendous limitations.

Apart from being hideously expensive, difficult to train cinematographers and directors on using the process as well as having noisy and enormously cumbersome cameras; one of the most significant issues with Technicolor and all of its competitors was that you needed A LOT OF LIGHT in order for any kind of image to appear on the film. So much light, in fact, that it became impossible to shoot anything in the dark or shadowy areas of a set or location. To put it simply, with colour film you could ALWAYS shoot images like this:

But you could NEVER shoot images like this:

So if you’ve ever wondered why classic colour film from the 1930’s till the 1960’s all look so different from modern films? Now you know. And it is also for the same reason that black and white films still maintained popularity during these decades simply because colour was a useless medium for shooting films that required shadowy or moody photography; especially thrillers, horrors, film noir and suchlike.

It wouldn’t be until the mid-1960’s with the advent of many other competing color processes (including a Kodak single-strip color film, somewhat ironic since thirty years prior George Eastman, the founder of Kodak, threw Herbert Kalmus out of his office when he tried to sell the Technicolor process to them) that colour film began to reach the reactive states of ‘ordinary’ black and white film, allowing the gradual ability to film shadowy images (although this process would still take another 30 years to perfect…just in time to be replaced by the newly founded digital camera industry).

SO:

The development of realistic sound for film: 100 years.

The development of realistic colour for film: 50-60 years.

What does this have to do with 3D?

3D has been around for almost as long as sound and colour, the science of stereoscopy invented in the mid-19th Century with such devices as the Stereoscope (the progenitor of the popular Viewmaster toys). The first publicly shown 3D test (using the anaglyph system) was in 1915 while the first 3D feature (The Power Of Love) was screened in 1922. In the 1930’s, a range of short subjects and documentaries – mostly obscure – were produced using various 3D methods. Even Nazi Germany produced two 3D propaganda films and apparently experimented with the technology heavily.

However the real boom in the 3D film world didn’t really happen until 1952 when the technology and filmmakers/studios were comfortable enough to work with ‘standardized’ 3D formats and began working with cinema chains to bring feature-length 3D films to audiences. The first, a rather exploitative jungle film entitled Bwana Devil setup many of the tropes and cliches of the 1950’s 3D film, but proved to be a huge success as the first 3D film with wide distribution. This was followed by a proverbial ‘golden age’ of 3D films with productions of such well-received and incredibly successful classic films such as Jack Arnold’s Creature From The Black Lagoon and It Came From Outer Space, Hitchcock’s exceptional Dial M For Murder and the Vincent Price headlined remake of House Of Wax (with a famously pointless, but fun, ping-pong sequence).

Of course we’re talking about new technology and movies here…so things were not destined to go that well. Just as reels of film would jam and burst into flame during screenings of The Black Pirate, the first 3D films were plagued with problems because they needed two projectors to be screening the film in PERFECT synchronization, coupled with the fact that the early 3D silver screens would not reflect light to the sides of the theater and a lot of sloppy cinemas and projectionists failing to keep an eye on the screenings ensured that audiences were given a less-than-stellar treatment of what was a pretty amazing effect. Let down by the expense and difficult science of recording and projecting 3D films, plus audience dismay at bad screenings run by uncaring cinemas and an unending onslaught of genuinely terrible 3D films that offered little artistic value for story or properly executed stereoscopy, box-office tallies began to slump and 3D was put on the shelf by the end of the 1950’s.

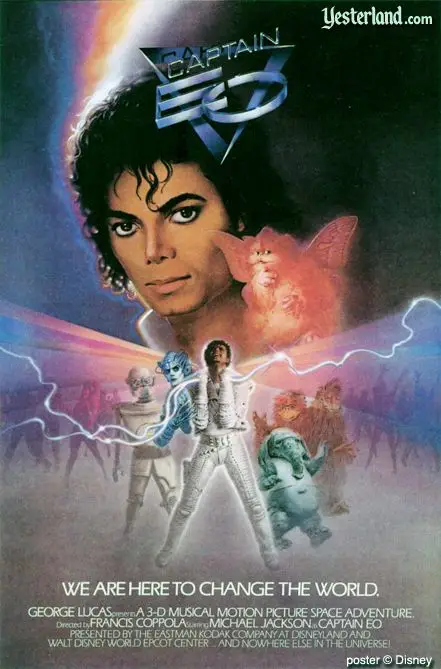

Although many exploitative 3D films remained in production continuously from the 50’s to the modern day (particularly as a horror vehicle in the 1980’s with such films as Jaws 3D, Amityville 3D and Friday the 13th Part III-D), it wasn’t until the late 1980’s did people begin to examine stereoscopy again — a charge led by the advent of many ‘gimmick’ 3D films executed by enthusiasts of the technology such as the IMAX corporation and George Lucas/Disney with their famous Michael Jackson 3D short film/attraction Captain EO.

It’s interesting to note that Walter Murch himself worked as editor on Captain EO and makes some comments about his experience in his letter. I was lucky enough to catch the film both during its initial run in Disneyland the year it opened and also again a mere 6 months ago since it’s tribute-reopening. Incidentally there’s a LOT to be said about nostalgia, the 3D in Captain EO, while being somewhat ‘eye-pokey’, is no better than the films you see at your local cinema today. Perhaps during the 80’s the effect was phenomenal, but the stereoscopy of the film is no longer exceptional today.

But it wasn’t until another 15 years later that 3D re-entered the mainstream cinema — slowly and guided by IMAX as a primary exhibitor with films like Robert Zemeckis’ The Polar Express and special 3D-segments in films like Superman Returns and several of the Harry Potter films. These 3D segments are fascinating in that they mirror so much of the ‘colour’ segments inserted into black-and-white films during the 20’s-30’s and ‘talkie’ segments in The Jazz Singer and similar films of the era. Funny how history repeats itself eh?

And then came – what I like to call – the 21st Century’s version of Snow White & The Seven Dwarves: a little film called AVATAR.

And this where I come – finally – come back to Walter Murch. See, I don’t know what Murch observes when he watches a film like AVATAR or How To Train Your Dragon or Tron Legacy in 3D, but I know what I see.

I see Snow White & The Seven Dwarves. I see The Jazz Singer. I see The Black Pirate. I see something only in its infancy: two-strip Technicolor, scratchy, mono, hard to hear audio, shadowless colour-film that can’t quite shoot in the dark.

It took us a century to develop the technology that gives us the quality of sound we hear in cinemas today. It took us 50+ years to give us the beginnings of colour in movies that looks anything like what our eyes see everyday (and believe me, we’re STILL wrestling with this in the industry today). So why shouldn’t it take 3D just as long to finally resolve into something that will be as realistic as every other aspect of films that we enjoy already? Why be so down and hard on 3D, especially since it’s had far less time to gestate given how expensive it is — so much so that it’s really only corporations and empire-building filmmakers like the James Camerons, Peter Jacksons and George Lucases of our world can really invest the capital into perfecting it?

Murch’s assurances that 3D does not work not only connotes the literal, but also the aspirational. Ebert flat out (and I think a little foolishly) goes one step further and spells it outright: that films are to be two-dimensional, now and forever. How is it that two bright and well-educated men in the history of cinema and it’s close link with scientific endeavor could so easily forget the one-man-viewable only Kinetoscope or Kalmus’s glued-together-Technicolor film strips? How could they forget that even though film is always subjective, every generation lives in an age where the medium is inching one-step-closer to the infinite horizon of ultimate suspension of disbelief and that journey is driven not just by storytelling, but by the technology that allows those stories to be told?

I know this is a very long read and I swear that I’m almost done. Before I go I just want to glance over again, quickly, the contents of Murch’s short essay:

“The 3D image is dark, as you mentioned (about a camera stop darker) and small. Somehow the glasses “gather in” the image — even on a huge Imax screen — and make it seem half the scope of the same image when looked at without the glasses.”

Firstly, this is not exactly true. There are many 3D systems in operation today – polarized (Real D, Disney 3D), interference (Dolby 3d), eclipsed (X-PanD) and more. Not all of these systems reduce light as significantly as a camera-stop, in fact my preferred 3D system (Dolby) limits light-loss significantly. Any of you who live in Auckland can try out the Dolby system at your local Event Cinema: it’s the screenings where you have to return your 3D glasses rather than being allowed to keep them. Secondly, the notion of a reduced image is subjective — even if the optics of reduction through the concave lenses of the glasses apply.

“I edited one 3D film back in the 1980’s — “Captain Eo” — and also noticed that horizontal movement will strobe much sooner in 3D than it does in 2D. This was true then, and it is still true now. It has something to do with the amount of brain power dedicated to studying the edges of things. The more conscious we are of edges, the earlier strobing kicks in.”

James Cameron disagrees with Murch on this point and suggests that the horizontal movement strobing/ghosting (though caused by the human brain’s visual cortext) can be reduced by increasing the frame-rate of a film’s photography and projection. Cameron has made claims he intends to shoot AVATAR 2 at 60 frames-per-second instead of the standard 24 and your local cinema’s digital projector will be able to project the film back at 60 frames-per-second, which will nullify the strobing effect. We shall have to wait and see whether it’s Cameron or Murch that will be proven correct. Interestingly Ebert, while anti-3D, agrees that film projection speeds need to be increased as a general rule for maintaining a high quality image.

“The biggest problem with 3D, though, is the “convergence/focus” issue…the deeper problem is that the audience must focus their eyes at the plane of the screen — say it is 80 feet away. This is constant no matter what.”

And Murch is completely right — this one of the principle issues with 3D as it is today and the cause of so many of the ‘headache’ complaints (though not as common as you may think). But, of course, this is a problem to be overcome, just like every other aspect of filmmaking from the moment Edison demonstrated his ‘motion picture camera’. Simply dismissing 3D as a whole by claiming this is ‘unsolvable’ does a great disservice to the hard work of people like Kalmus or Edison or other pioneers who overcame such seemingly impossible problems….incidentally problems which were only overcome because audiences grasped on so tightly to things like muted, fuzzy, over-lit colour films and scratchy, mono, muffled, low-fidelity talkies. Without people demanding more, the technology would have no drive to perfect itself.

And what I disagree with Murch and Ebert most of all is their notion that we SHOULDN’T be demanding more, that we should merely give up and walk away. This sort of stubborn ludditism shouldn’t be coming from one of the most respected film critics alive today and the man who edited Apocalypse Now and won an Oscar for editing Cold Mountain on a Power Mac with an early version of Final Cut Pro. Not when the entire weight of history is against them on this particular matter.

Anyways I’m done. Sorry, that was a long rant/history lesson. And don’t get me wrong: Walter Murch is right in so far as that the modern technology of 3D is not without its limitations and it isn’t ‘real’ 3D as it were. But I can’t agree with him that it’s not going to get better. A 19th Century person viewing a short film through a Kinetoscope would have no conceptual imagination to envision Terminator 2 or AVATAR 3D or even Snow White & The Seven Dwarves. A filmmaker in the 1950’s would be hard pressed to get their minds around the notion of films being recorded, cut, finished and projected entirely out of a computer; just zeroes and ones.

And yet we’re somehow supposed to believe that 3D is a vulgar gimmick, a dead-end on the road of cinema, a pointless diversion that cannot and will not possibly get better?

REALLY??

Sorry, but you’ll have to excuse me if I don’t want to be the next George Eastman. For the next wee while I’m more interested in seeing where 3D is going rather than using it as some sort of technological boogie-man to explain why movies are sucking so much of late. Especially since, despite the very loud bleats of protests and complaints of 3D flaws, the number of audiences for 3D films is still growing with every passing year.

No offense to Murch and The Ebe of course.