The Choppiest Of The Sockeys

If you haven’t had the chance to check out the new Indonesian martial arts sensation (dubbed by many as the greatest action movie made in the last ten years) – The Raid – then you owe it to yourself to get your ass out to the cinemas now and see this low budget (a meager $2 million USD – cheaper than many New Zealand films), festival and theatrical sensation (be sure to see our write-up, trailer and NZ session times on the main Flicks site).

In acknowledgement of this breath of fresh air at our multiplex, I figured I should – as all film bloggers must and have already done by tradition – write the very unoriginal article on my favourite martial arts movies and/or fight sequences. For my part, I’m going with actual fights rather than entire films and, along the way, we’ll take a quick slide into the cinematic tradition and history of chop-sockey-cinema. So get yourself into a good horse-stance (feet shoulder length apart, pelvis out, shoulders back), pour some green tea and let’s get stuck in!

Nothing is ever as easy as it seems in this film critiquing business and even something as deceptively simple as martial arts movies gets tricky when you get right down to it. Just what exactly constitutes a “martial arts film?” The term ‘martial art’ derives from the tradition Chinese words that describe their ancient fighting system: ‘wu’ (martial) and ‘shu’ (art), which also gives the eponymous modern Chinese fighting style Wushu its name. Technically, however, you could argue that ANY kind of artform that involves self-defense IS a martial art. Gunplay, brawling, skillful driving, knife-work, aerial-combat, submarine warfare, they’re all martial arts in of themselves and, by definition, most action movies ever made are technically ‘martial arts’ films. So that’s a pretty crappy definition all round, especially when one considers martial arts films as a separate genre to the action and adventure films.

For my part, I define ‘martial arts films’ as cinema that emphasizes storytelling and the overcoming of obstacles by physical combat which is realized by the skill of the performers instead of visual effects. That’s a three-component definition: 1) it uses physical combat as part of the story and uses storytelling to create incidents of physical combat 2) the combat is used to overcome obstacles and characters in the story to move the plot forward and 3) the combat is realized by the actual, trained skill of the performers and is an actual display of human ability instead of visual effects or superior use of machines over manpower. Pretty specific…and yet still surprisingly vague when you think about it. But for the sake of argument, it’ll have to do.

Suffice it to say you won’t see any Stallone or Schwarzenegger films on here nor necessarily any boxing or gunplay films. Steven Seagal…well he’s not appearing on this list and let’s just leave it at that (neither is Chuck Norris, but by Internet tradition one could argue the entire list would be just a clip of him roundhouse-kicking on a loop).

Back to a little bit more theory: categorically similar to the principles of dance theater (such as Russian Ballet, Indian Bharatnatyam, Laotian Lam Luang or Japanese Kabuki), classical martial arts films utilize bodily ability and movement as an externalization of character and a means by which stories unfold (to varying degrees of success and believability). Because cinema tends to attempt to reflect reality rather than exaggerate as metaphor, the analogy of dance theater DOES fall apart since highly stylized and unrealistic martial arts fight sequences must be interspersed with realistic depictions of characters, story and dialogue. However these limitations allow for instances of greater creativity in weaving a suspension of disbelief in the audience that builds greater suspense and spectacle if done right (and unintentionally hilarious failure if done wrong). In short, martial arts films work because the performers can do a large amount of amazing feats in real-life which is a point of fascination for audiences to watch…and that the BEST martial arts films work when the audience believes that the CHARACTER can do almost EVERYTHING that they see on-screen as well.

The primary device by which martial arts films build a sense of ‘realism’ in its conflicts is through the system of traditional martial arts, particularly ones from Asia i.e. ‘Why does the hero use his feet and elbows to beat the bad guy to a bloody pulp? Because he’s specifically trained in a kind of martial art that empowers him to BE the hero of the story.’ Essentially, what that means is that a lot of martial arts movies are ABOUT people who are learning martial arts or are experts in those arts and using them to solve problems. The usage of martial arts and astonishing human skills for entertainment dates back pre-cinema to the world of traditional folk theater across most Asian and some Western cultures, but none with more emphasis than the art of Chinese Opera.

For centuries the art-form of Chinese (or Cantonese) Opera had flourished side-by-side with martial arts schools, the opera often being the only place one could learn classical Chinese Wushu when it was banned by various governments to suppress the risk of rebellion. By the early 20th Century, when the first film cameras began to arrive in the East, the opera was an fantastical mixture of song, dance, acrobatics, pyrotechnics and – most importantly – Wushu. Although early footage from the period amounted to little more than documentary clips of performances, it soon became clear that stories and skills from the stage could be translated to the silent screen. Spurred by the popularity of wuxia (martial chivalry) novels of the period which depicted epic fantasy tales of flying heroes, magical powers and zen philosophy, the first martial arts films were born. Some of the earliest known titles, including the 27-hour serial The Burning Of The Red Lotus Temple and The Swordswoman Of Huangjiang, were epic silent melodrama (not dissimilar to fantasy films like Zang Yimou’s epic Hero and Andrew Lau’s The Storm Riders) intercut with stylized Chinese opera martial arts displays, but it was a seed from which a whole and very unique genre grew.

From there, the genre began to grow. Domestically, martial arts appeared in both documentary and fictional films throughout Asia, notably in Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong and China though it was always Chinese and Hong Kong cinema that defined the genre for decades to come. Political rumblings quashed the wuxia film genre and, by the 1950’s, filmmakers were forced to rely more gritty, realistic stories that used non-supernatural Wushu applications, giving rise to a series of movies starring Hong Kong’s most famous and revered actor Kwan Tak-Hing, who portrayed Chinese folk hero Wong Fei Hung in 77 movies (a world record). Tak-Hing was notable for being a practicing master of White-Crane style Wushu and a respected Lion-Dancer who lent a skillful authenticity and athleticism to his performance that made him a superstar of his time. Meanwhile in Japan, director Akira Kurosawa – himself descended from a noble samurai family – reinvigorated national interest in the bushido-heritage of the country with his classic samurai films Yojimbo, Sanjuro and Seven Samurai.

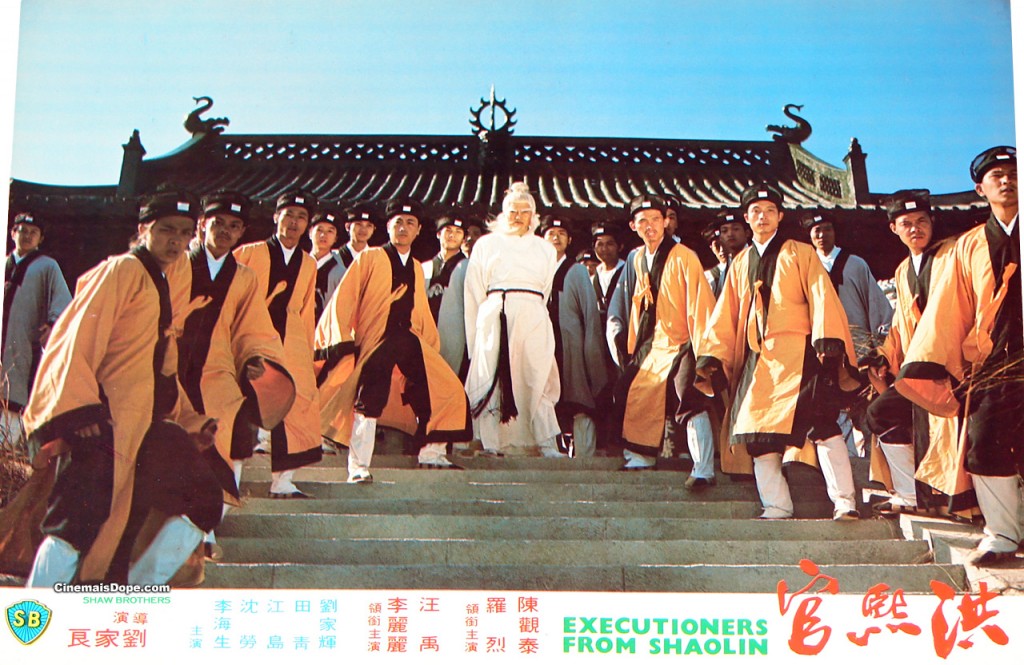

By the 1960’s, the most famous company ever associated with martial arts films rose to power: the Shaw Brothers Studio, operated by Run Run Shaw and Run Me Shaw, gradually created the infrastructure for the largest film production company in Hong Kong. Influenced by Japan’s samurai films and the new relaxed government attitude to wuxia, the Shaw Brothers produced a barrage of classic myth-and-mysticism films including Dragon Inn, The Five Deadly Venoms, The One-Armed Swordsman and the superb genre masterpieces 36th Chamber Of Shaolin and Eight Diagram Pole Fighter.

The infrastructure and facilities setup by the Shaw Brothers, plus the influx of money from the new-found martial arts cinema industry they helped build, led to a slew of competing production companies and producers, thus ushering the so-called ‘New Wave Of Kung Fu’. Though still firmly producing period pieces set between the 16th-19th Centuries (the notion of martial arts working in a modern context was still unusual at this stage), the new wave producers began an outpouring of low-budget, rip-off-each-other, concept films that 1970’s Hong Kong Cinema is renowned for. Amidst the fly-by-night operations, slave labour and dirty deals were the hard-working, but not-yet-blossomed, superstars of the next decade such as directors John Woo and Yuen Wu Ping (both slumming it making bizarre fantasy films), martial artist and actor Bruce Lee (tempted over by Raymond Chow after he built up a cult-following playing Kato in The Green Hornet and Batman TV shows) and the graduates of the famous Peking Opera performance group Seven Little Fortunes: Jackie Chan, Sammo Hung, Yuen Biao and fight choreographer Corey Yuen.

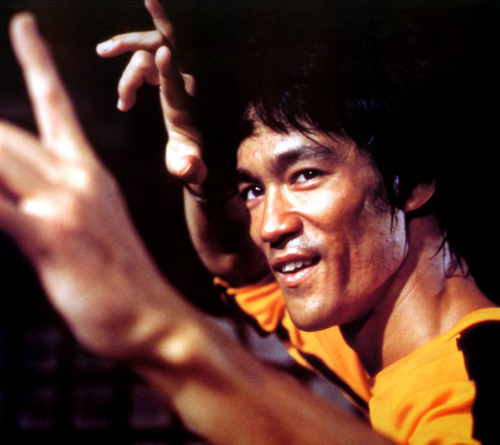

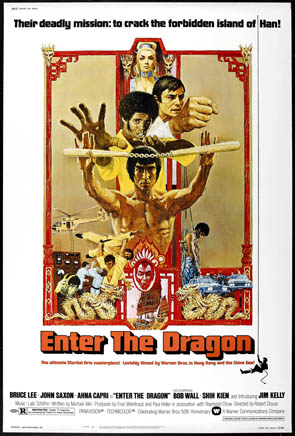

Bruce Lee was, of course, the tipping point in the scale. Though ‘Kung Fu films’ were being exported to the West since the 1950’s alongside their Japanese counterparts, it was Lee – an American-born and educated martial artist who had struck minor Hollywood fame – who almost single-handedly propelled martial arts and its cinema into a permanent fixture in Western culture. Though tragically short-lived as his fame was (he became a household name after his death in 1973 and was only a cinema celebrity in the last three years of his life), his indelible charisma, showmanship, insistence in developing a more high-impact and faster style of fighting for the screen and the popularity of his four films (finishing with the Hollywood produced blockbuster Enter The Dragon, released after his death) set his name as an immortal in popular culture. And with Lee’s immortality came the Western public’s fascination with martial arts and chop-sockey cinema.

Lee’s nefarious habit of discarding time-honored traditions in martial arts practices as well as cinematic conventions in his, almost obscenely, low-budget films inspired a whole generation to – at first – rip off his success and then to genuinely follow in his philosophy. While chop-sockey films declined in other countries post the 1960’s high of the Shaw Brothers era, it continued to motor along at its own pace in Hong Kong. And these pioneers began to usher Hong Kong action cinema into the modern age by breaking the habits and traditions that kept martial arts films in the area of low-budget, unimportant, cliche, period movies. The notoriously ambitious and driven actor, director and choreographer Jackie Chan began to experiment with the idea of turning martial arts choreography into a thing of true spectacle, showing unbelievable physical feats, speeding up choreography to make it more realistic, performing literally death-defying stunts and demanding astonishing levels of perfection (in his 1982 film Dragon Lord, Chan executed a fight scene that required a world-record 2,900 takes for a single shot). Chan expanded his repertoire by being among the first filmmakers to set martial arts in a modern era with his incredibly popular series Police Story as well as defining the ‘Comedy Kung Fu’ genre which incorporates slapstick and light-hearted fights in low-budget blockbuster films such as Drunken Master and Snake In The Eagle’s Shadow.

Subsequently the 1980’s were dominated with three action genres that not only would own the box-office for the decade to come, but revitalize Hong Kong’s film industry into a mammoth machine of production and distribution. One corner would be ruled by Jackie Chan and his world-famous Jackie Chan Stunt Team, constantly pushing the envelope with his unique combination of humour, jaw-dropping stunts and clever fight choreography set in larger-than-life situations. Another would be ruled by John Woo, now come onto his own after the success of his Chow Yun-Fat starring blood-and-bullets action films A Better Tomorrow, Hard-Boiled and The Killer; all revolving around melodramatic revenge stories about Hong Kong’s gritty underworld. The final pillar holding up the genre would belong to Tsui Hark, the go-to man for Hong Kong’s blockbusters including third revival of the wuxia genre (with films like Zu Warriors From Magic Mountain) and epic dramas (like Shanghai Blues and A Chinese Ghost Story). At the same time, in Japan, Korea, the USA and in Europe, a new B-movie subculture of martial arts cinema would be born and hungry for content, in turn starting up a low-budget straight-to-video industry in each respective country. By the end of the 1980’s and early 1990’s, these percolating industries would overflow with A-list stars (and A-list projects) such as Chuck Norris, Steven Seagal and Brandon Lee. After several failed attempts to cross over into Hollywood in the 70’s and 80’s, Jackie Chan would slowly migrate to the USA and English-language cinema in the 90’s while a new, young star would rule the roost in Hong Kong by the name of Jet Li. A charismatic and record-breaking Wushu prodigy trained in mainland China, Li forayed into the world of film after decades as an undefeated Wushu athlete. His first outing would be the seminal classic Shaolin Temple, though he would not become a household name in Asia until he portrayed Wong Fei Hung in Tsui Hark’s blockbuster wuxia Once Upon A Time In China series of films.

The 1990’s saw the rise of popularity of martial arts cinema both in the East (where mainland China, Korea and Japan once again started investing heavily in the genre) and in the West (with the rise of stars like Wesley Snipes and Jean Claude Van Damme and the appearance of martial arts in TV shows, video games and films. Hong Kong was booming with Wushu and wuxia films being the primary money-earning blockbusters of the industry and heavily exported to Western countries on video and DVD. And then of course came the revolution.

By 1998, the presence of martial arts movies began to saturate Western popular culture at extraordinary levels. Jackie Chan’s independently produced English language films like Rumble In The Bronx, Who Am I and Mr Nice Guy had stirred up a hungry audience eager for more. John Woo had migrated to Hollywood and was already climbing the studio ladders and bringing his deft mixture of gunplay and chop-sockey into the films he was producing. The success of films like Kickboxer, Mortal Kombat, Blade and Hollywood IMPORTED (and redubbed in English) movies such as Fist Of Legend and Iron Monkey was adding more mass to the rolling snowball.

And finally the avalanche started.

Between the release of Jackie Chan’s first major A-list studio film Rush Hour (1998), Jet Li’s own successful migration to Hollywood which saw the release of four A-level martial-arts films in two years (Lethal Weapon 4, Romeo Must Die, The One and Kiss Of The Dragon), the sci-fi, martial-arts blockbuster The Matrix (1999) and Ang Lee/Miramax’s Hollywood-financed arthouse wuxia epic Crouching Tiger Hidden Dragon (2000), the term “Kung Fu” was on everyone’s lips and the whole world wanted a piece of the action. By the turn of the 21st Century, martial arts was no longer niche, but a vital element to consider in most Hollywood action productions and the renewed interest in genre scaled up the production values and budgets of Hong Kong’s own film industry. Modern 21st Century martial arts films are no longer B-movie trinkets, but expensive A-level epics that compete on an international level in an attempt to hold onto the audience created during the early 2000’s. In the West, the whole stunt industry has changed as has the way we do fight sequences in modern films which is now strongly reliant on a high level of technique, elegance and grounding in a variety of fighting styles; many originated in Asia. Whether you’re James Bond or John Carter, you’ve got to swing a sword like you know it and you’ve gotta out-flash the previous guy if you want to grab the audience’s attention and make their palms sweat in nervous anticipation.

And so we end up back in 2012.

So what makes a great fight scene? In all the years I’ve watched martial arts films, I’m pondered about what makes a fight work and what doesn’t. Naturally opinions are divided, people have varied tastes and demand to see various things; however I think that – for my part – my ideal perfect fight is made up of equal measures of four components:

1) Tell a story

2) Involve the audience

3) Show something new

4) Restraint, restraint, restraint

The first thing a good fight scene should do is both contribute to the story of the film and have a story in of itself. The first is a matter of screenwriting; the best martial arts movies always construct plots where fighting is inevitable i.e. there’s no way around it, there’s no way to prevent it, it’s always someone backed into a corner or a last, desperate attempt for salvation. A fight scene should be the means to an end, not an end unto itself; the best fights happen in the midst of a dramatic motivation (e.g. James Bond and Oddjob’s battle inside Fort Knox in Goldfinger isn’t about the good guy and bad guy fighting, its about the good guy trying to stop a nuclear bomb from exploding and the suicidal bad guy getting in his way and the fight happens because of this conflict; thus story always motivates the fight). The second is a matter of choreography and direction; the best fights tell stories and the best stories are ones that which contain elements that the audience can relate to. Likewise, fight scenes should always have a structure filled with surprises, twists, turns, escalation of danger, escalation of stakes (e.g. the Goldfinger example has the nuclear bomb timer is counting down to zero) and essentially runs like a mini-movie or short film.

Involving the audience is related to the idea of telling a story. Audiences are not experts at martial arts and don’t have an invested interest in its technical aspects. So what if a character can punch real hard or kick really high? Big freakin’ deal! Who cares? As a result, audiences rely on character performances, photography, editing and direction to get an insight on what’s going on in order to figure out who’s winning, who’s losing, who’s the better fighter, who’s tired, who’s hurt and gain an appreciation for some of the more clever moves, skills and stunts that happen on-screen. A lot of generic chop-sockey films tend to grossly self-indulge on their choreography and over-the-top stunts, but fail to make the fight understandable or relatable for the audience; resulting in a long, tiresome, nonsensical mix of flashy techniques that zip past camera or repetitive punching and kicking that doesn’t engage. Engaging fights should make an audience feel like they understand what’s going on and that they can appreciate when the hero does something clever or the villain does something terrifying because of the way it is choreographed, shot, edited and presented as a story-element rather than a quick movement that you’d miss if you blinked. It is for this reason that many of the more successful films of this genre involve stories of someone learning a martial art because the audience goes through that learning process with the protagonist and then gets to see the hero use the same techniques in future battles (e.g. the Drum Technique strike from The Karate Kid Part II or the 8 Drunken Gods demonstration sequence in the original Drunken Master). Good choreography and good filmmaking have to work together, in a cohesive and understandable manner, in order to make fight scenes accessible for the largest audience possible.

Showing something new is tied fundamentally to involving the audience; because audiences don’t know how martial arts work, it all tends to look the same. There is only so many punches, kicks, elbows, jabs and screaming headbutts that an audience can take before it turns into a boring and incomprehensible malaise of limbs and sound effects. Good martial arts films tend to be ambitious and ambitious fight scenes always find a unique lynchpin, an intriguing concept, a never-before-seen idea to ground each sequence in order to make it memorable. Looking at Jackie Chan as an example, his gradual understanding of his art-form created an awareness for doing fight scenes using household props like chairs and ladders (e.g. First Strike) or outlandish, uncontrollable human emotions (Fearless Hyena) in order to both dazzle the audience and make the fight relatable to within their own realm of experiences. Flying feet and fists is never actually all that interesting, but flying feet and fists can be presented in new, exciting and never-before-seen ways.

The last point is all about restraint and it encompasses all the points above. The biggest sins in martial arts films are their over-indulgence in fight choreography and lack of concern for story and the audience who has to sit through it all. Bad films are a never-ending barrage of punching, kicking, falling over, rinse, repeat, scene-after-scene and often fail to make the plot move forward as well. The secret to over-coming all of this is restraint, restraint and more restraint. A fight scene that’s two minutes and brilliant will support and energize a film far more than a scene that’s seven minutes and mediocre. A 20-second scene that propels the story is far more valuable than a 60 second scene that’s full of flash choreography that doesn’t mean anything. A lack of restraint kills the attention-span which sucks away suspension-of-disbelief and makes the drama and dialogue moments of the film all the more worse which then translates to even less suspense in the fight scene that follows. Like all the best roller-coasters, the overall experience of watching a story punctuated with fights should build and build to an unbelievable level of tension which releases and builds again. And like all the best movies, restraint is always required to keep you from flying off the rollercoaster tracks.

Keeping all these points in mind, I present my own personal favourite fight scenes from martial arts films. They don’t necessarily come from great movies, but each one highlights something important, something powerful and eye-catching, that drives home the idea of what great fight scenes should look like, sound like and feel like.

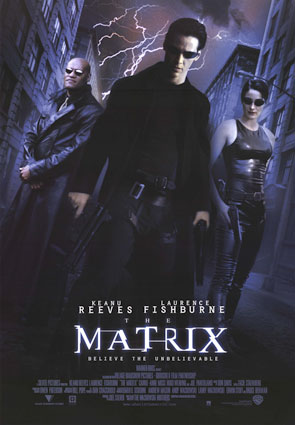

The Dojo Fight from THE MATRIX

Some would argue an all-too-obvious and shallow entry to a list, but over-exposure does not equal over-baked. In a virtual reality simulation world that exists only as a computer-construct between human brains, master and rebel leader Morpheus (Lawrence Fishburne) tries to teach his protege Neo (Keanu Reeves) both the fine art of hand-to-hand combat, but also how to use his mind to manipulate the artificial world in which they’re sparring. Choreographed with astonishing restraint (for fight director Yuen Wu Ping at least), the dojo fight is an ambitious and carefully measured conversation pitting a variation of styles and philosophies against each other; Neo – who is young and brash – constantly opts for fast, aggressive, light-footed, hard-hand styles ranging from an opening Northern-style Wushu stance before switching to variations including Jeet Kun Do and Tae Kwon Do. Morpheus, older, more experience, responds with a serene, firm-footed and calculated servings Tai Chi, Hung-Gar and Eagle-Claw styles which emphasize on grapples, foot-traps and muscle-attacks. No other fight scene in the rest of the Matrix trilogy comes close to this gem as no other scene makes the audience genuinely feel a sense of connection with Neo, who is learning the intricacies of fighting, and tells a clear-cut story arc that is about education, not violence. What makes it all the more impressive is that the scene is executed largely by the actors instead of stunt-doubles which is an absolute joy to behold. Thirteen years on, its still jaw-dropping.

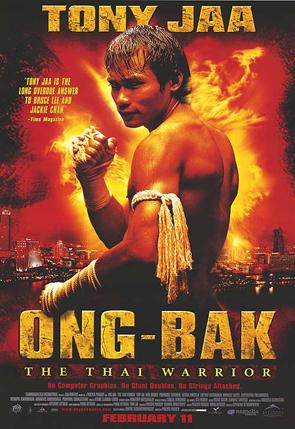

The Footchase from ONG BAK: MUAY THAI WARRIOR

When it comes to the element of ‘showing something new’, you can’t overlook the impact of Thai actor and martial artist Tony Jaa and is skull-cracking, eye-watering, knee-weakening debut in Ong Bak; the film which – almost single-handedly – kick started Thailand’s growing martial arts cinema industry. Blending a strange, but effective mix of innocent country-bumpkin comedy and genuinely dark and unsettling themes reflecting Thailand’s cultural destruction, the film tells the story of Ting, a simple-minded village boy who has spent his life studying the traditional Thai martial art of Muay Boran who is sent to Bangkok to retrieve a sacred idol from treasure hunters. Ting falls in with a pair of scam artists who eventually befriends him, but not before their crimes catch up to them as you’ll see in this clip. Though more of a chase scene than a fight sequence, Jaa here capitalizes on his agility and screen presence to almost lay claim on having the best free-running scene committed to film even though there had been many prior and what Jaa does here isn’t parkour or free-running so much as it is ‘showing off’. Regardless, the self-promoting quality of the stunts ties in nicely with the goofy humour of the film and delivers a fabulous sequence that Jaa, sadly, has never topped in his surprisingly dull and homogenous career since the release of this genre-classic.

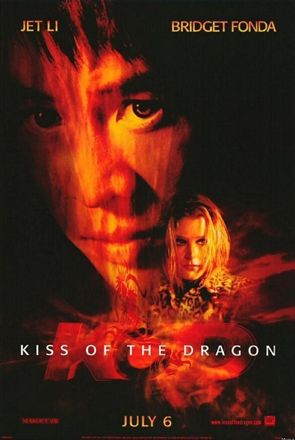

The Police Training Gym from KISS OF THE DRAGON

Kiss Of The Dragon probably gets a worse rap than what it deserves, being a standout example of all-the-right-elements put together in slightly-the-wrong-way. Story, location, style, caliber of cast, it could’ve been a very good thriller, but it sadly stumbles into the realm of expensive actioner instead. Regardless, it does offer selections of eyebrow raising fight material including this – the film’s most memorable moment. Near the finale of the film Chinese intelligence agent Liu (Jet Li), who’s had his shit messed with one time too many by scenery-chewing corrupt cop (Tchéky Karyo), storms a police precinct for revenge and to rescue a hooker-with-heart-of-gold (Bridget Fonda) and her child from their nefarious clutches. The sequence, expertly handled by Seven Little Fortunes graduate Corey Yuen, is a perfect match for Jet Li whose training in Wushu and perfect body proportions makes his martial prowess leap off the screen. What makes this fight so delectable is its structure – here Yuen doesn’t waste a single second with idle, random, filler punches and kicks, but breaks both the choreography and camera movement down into neat sections which are completely different from each other and keep upping the ante, progressing the fight’s tension and keeping the audience’s interest. Even a casual observer could sit down with pen and paper and re-write the fight’s structure, explaining why each 8-10 second block is vastly different from what came before and will come after it. Combined with the restraint to keep the sequence short and dynamic, it all adds up to an experience that you can’t help, but find yourself leaning closer to the screen as you watch it unfold.

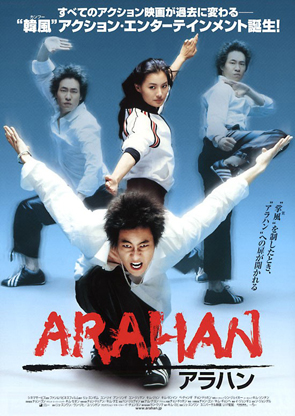

The Restaurant Fight from ARAHAN

Arahan is a largely forgettable, fluffy, South Korean equivalent of a wuxia film that paints the story of a bumbling cop who discovers that he’s the missing link in an ancient society who are fighting to prevent an evil force from invading the world. That story doesn’t even really fit into the fight sequence that is presented here, where the cop is harassed by underworld members (who have always bullied him) that don’t realized he’s now inherited magical Taoist superpowers and Kung Fu abilities, and it’s all the more stranger since there are no other fight sequences like this in the rest of the film (which is dominated by wire-work sword-fighting). None-the-less, if there is ever a reference-quality sequence of how to nail the four components of great fight scenes, this is probably it. In this remarkably short sequence you will see a fight that never EVER stops character development and storytelling, that constantly tries to show the audience something new, that constantly ups the ante and ambition (even elegantly mixing in some CGI shot-glasses) and has all the self-restraint to keep it short and sweet. The emphasis being not on showing off ability or how tough the stars are or how flashy the choreography is, but keeping the audience laughing and interested. You’ll notice that the camera doesn’t dwell on the fight as much as it does on the acting, the stunts, the dialogue and telling a visual comic story. In all my years of watching martial arts cinema, I’ve never seen a more perfect example of an ‘ideal fight scene’ as this. I swear this scene should be taught in film schools.

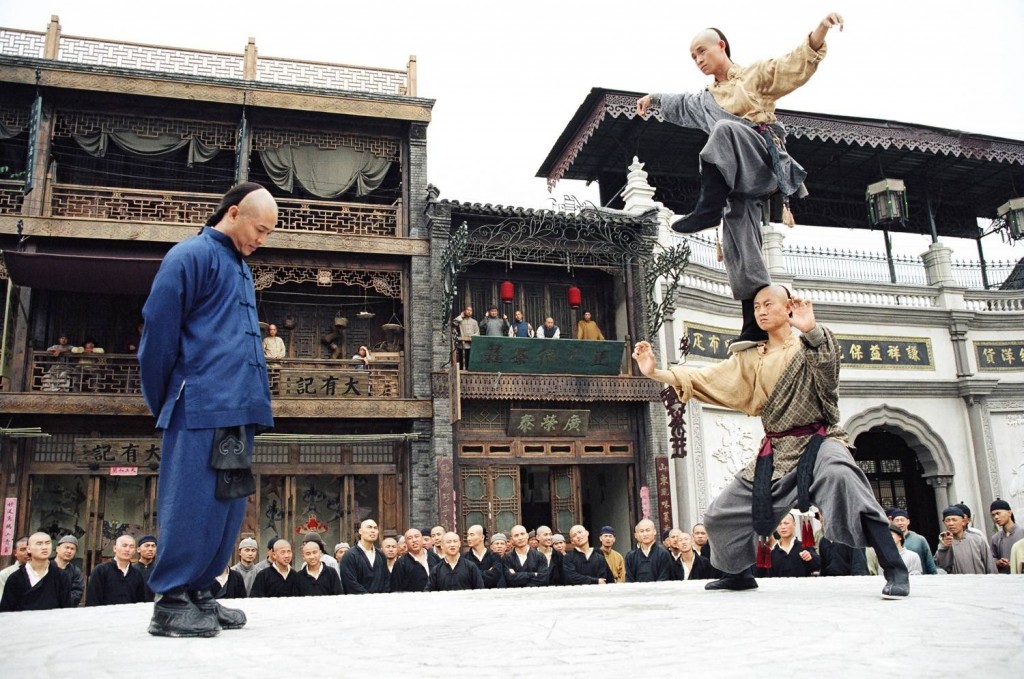

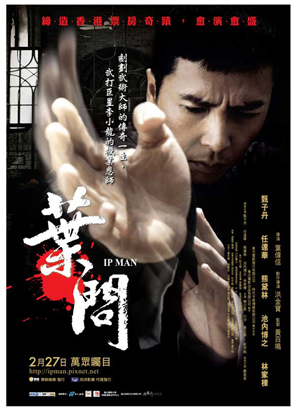

Ip Man vs The Northerner from IP MAN

Wing Chun is a martial art that’s practiced by an astonishing number of people all around the world, but its cinematic depiction has had it pretty rough. Creating effective and believable choreography to such a (supposedly) dogmatic style had proven difficult, but actor, director and choreography Sammo Hung had spent almost 30 years trying to bring it to the screen. While there have been other attempts to depict the style (like the wuxia-esque story of Wing Chun starring Michelle Yeoh and the more gritty, but still stylized Prodigal Son starring Hung’s Peking Opera brother Yuen Biao), it wasn’t until the epic biopic of Wing Chun master (and teacher of Bruce Lee) Ip Man came to the screen that Hung finally had the vehicle to produce the greatest Wing Chun movie ever made. In this scene, taken early from the movie, Ip Man (Donnie Yen) is harassed by an obnoxious Northern-style ruffian (played by the awesome Fan Sui-Wong, whom fans may remember from the Hong Kong gore-comedy Story of Ricky) who has come to show that he is the best fighter in town. Ip Man, pressured by the village elders, accepts the challenge to spar with the ruffian. What follows is elegance defined; a beautifully photographed, edited and executed sequence comprised of two exceptional martial arts actors with carefully woven moments of wire-work and light-hearted thrills. Ip Man features some of Sammo Hung’s best choreography in years and his ‘cracking the code’ of cinematic Wing Chun is a triumph that pays dividends as the scene progresses. Things to look out for are the excellent blends of dialogue (sadly not translated in this clip) and visual comedy as the ruffian repeatedly promises to pay for breakages in Ip Man’s house and a point where his own child interrupts the battle to pass on a message from his wife who is not impressed with the carnage going on in her living room. And of course nothing will stick in your mind as strongly as Ip Man’s trademark chain-punches at 02:15 that have become the signature of the movie and it’s sequel.

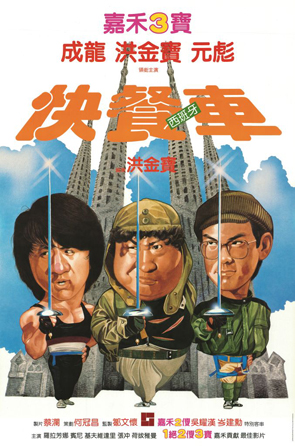

Jackie Chan vs Benny “The Jet” Urquidez from WHEELS ON MEALS

When it comes famous duels, fans all agree that Jackie Chan’s one-on-one against Karate and American Kickboxing champion Benny “The Jet” Urquidez is one of the best every recorded on celluloid. Chan squared off against Benny twice, once in Dragons Forever and again here in Wheels On Meals. A lot of fans prefer the former, but I like the latter. The story, which brings together three of the most famous members of the Seven Little Fortunes Peking Opera troupe: Jackie Chan, Yuen Biao and Sammo Hung, is your typical generic genre affair where two brothers who deliver takeout food and a bumbling private detective get caught up in a kidnapping plot involving an heiress played by former Miss Spain Lola Forner. In the finale, Chan wrestles with Urquidez while Biao and Hung play comedy interference tackling other members of the kidnapping gang. If there is one action star who is arguably exempt from the ‘restraint’ rule, then it is Jackie Chan. Chan’s trademark isn’t that he throws everything including the kitchen sink into his fight sequences (which he does), but that he’s got the creative chops to make something that lasts ten, twelve, even fifteen minutes long seem fresh and interesting with every passing moment. How does he do this? By making the audience feel intimately involved. His philosophy in fight choreography is to humanize the combatants as much as possible and then use it as creative inspiration; in Chan’s films the supposed martial arts ‘experts’ get hurt, get sore, slip on carpets, become dazed, stagger from exhaustion, have hilarious near misses and prat-falls, have their plans never work out the way they expect and, more than once, will stop to take in how ridiculous the situation they’ve ended up in is. In the process, audiences don’t just connect with Chan’s character, but with the opponent as well when they might bump their head into a door-frame or fall backwards onto a concrete floor (because we’ve ALL done that at some point in our lives). These humanizing elements help audiences follow the arc of the battle and feel an intimate connection with the thoughts of everyone involved. Not only is it fun, but it’s immensely satisfying and that’s why Jackie Chan is Jackie Chan.

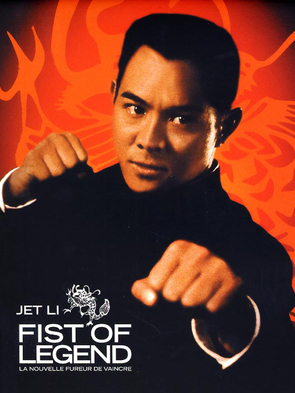

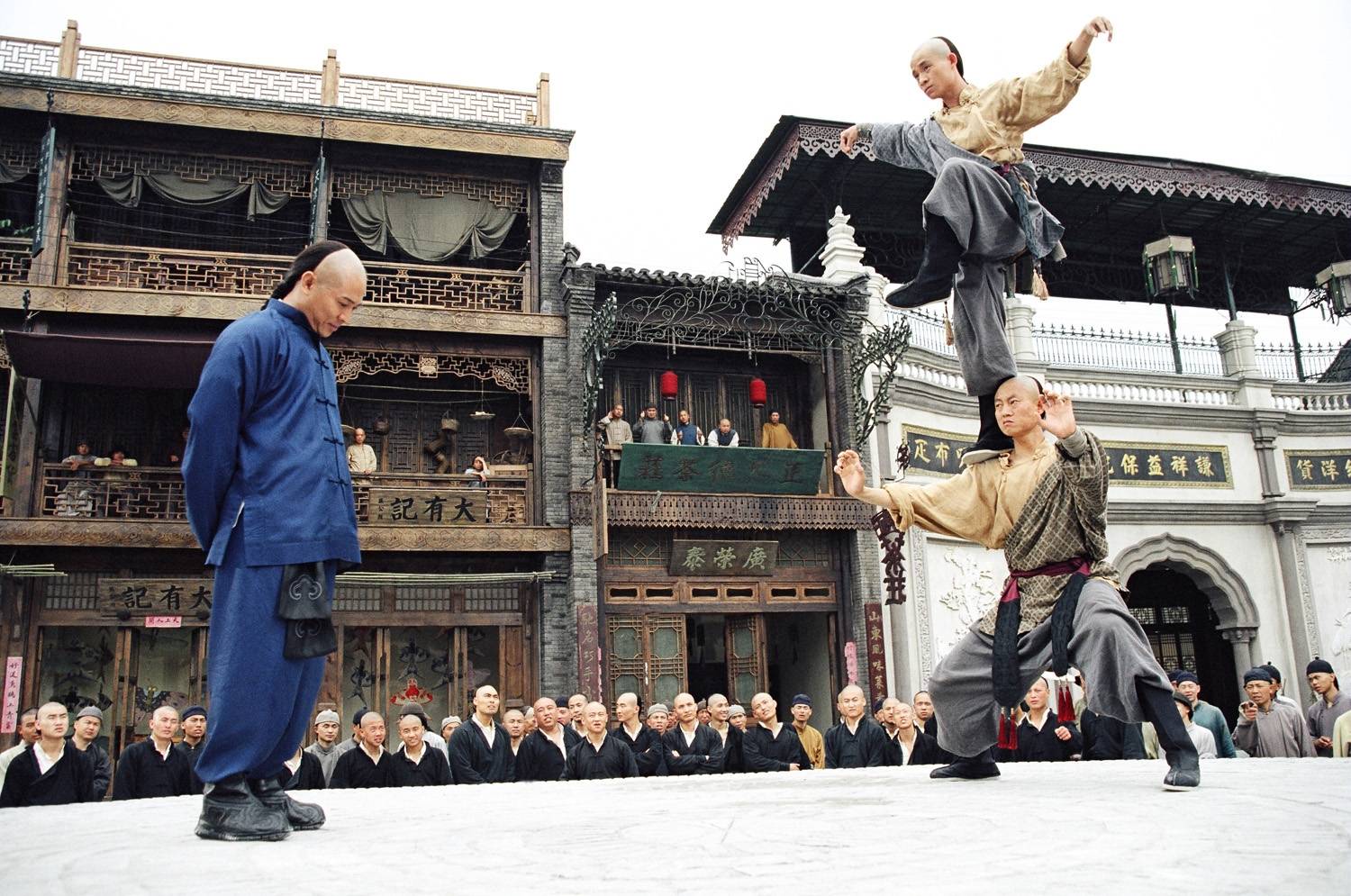

The Kwoon Courtyard Fight from FIST OF LEGEND

Fist Of Legend is a very faithful remake of the Bruce Lee classic Fist Of Fury. It’s also, according to many genre fans, possibly the greatest martial arts movie ever made. While it doesn’t lay claim to any particular strength, it is notable that – as a strictly Hong Kong film – it exemplifies the most ideal balance of story, acting, themes, production value and bone-crunching Kung Fu. The movie is another retelling of the story of Chen Zeng – a student of the Chin Woo martial arts school who returns home from abroad to find his master Huo Yuanjia (a real historical character who, ironically, is portrayed by Jet Li himself in his movie Fearless) murdered by rival fighters belonging to the Japanese occupation forces that rule Shanghai. Chen Zeng then unloads a brutal revenge against the Japanese. In this sequence, Chen Zeng’s acts of vengeance are challenged by Yunjia’s son Huo Ting’en (played by the brilliant Chin Siu-ho whom some may recognize from such classics as Mr Vampire and Tai Chi Master) and the two fight in the courtyard of the Chin Woo school for control over the organization. The film made an international star out of Jet Li (when the film was translated and re-released by Miramax) and many fans and fighters consider its action sequences to be among the best ever to be realized. Unlike every other entry appearing in this list, the fight sequences in Fist Of Legend contain NO gimmicks. There’s no deeper subtext, no clever use of props or humour, no ticking clock to race against nor any clever story-telling running parallel with the sequences. The battles are simply a bunch of people determined to beat the other person to death with their own two hands. The choreography, brilliantly realized by Yuen Wu-Ping, seems deceptively simple in its design, but is astonishingly difficult and is only capable of being realized by some of Hong Kong’s finest martial arts performers who conveniently happen to appear in this film. The action sequences are nothing more than a barrage of pure fighting technique, the characters lay into each other with everything in their arsenal with ever-increasing speed and ferocity. You’d think that after the first scene you’d be tired of this, but Wu-Ping ups the ante again and again until your knuckles are white with tension. Look at Li and Siu-ho’s perfectly executed stances, their kinesthetically smooth punches, their beautiful footwork and aerial kicks, their speed, timing and the subtle use of wire-gags. If other fight scenes appearing on this list are about creativity and craftsmanship, then this one is all about sheer physical ability and talent.

Lee vs O’Hara from ENTER THE DRAGON

If restraint and story-telling truly is a high watermark for action scenes, then nothing comes close to nailing those concepts like this; arguably one of the greatest sequences in Bruce Lee’s final and most successful film Enter The Dragon. Here, the action is way in the back seat as the scene is driven entirely by the narrative which portrays intelligence agent Lee (Bruce Lee) who infiltrates a martial arts tournament taking place in a remote Hong Kong island which is actually a cover for drug smuggling and organized crime. In this scene, early in the film, Lee squares off against O’Hara (Robert Wall) who doesn’t realize that he contributed to the suicide of Lee’s sister some years before. It’s all about the psychological exchange as Lee humiliates O’Hara with his exceptional speed and skills and then, when his opponent cranks it all up a notch, is forced to kill him and realize his bitter revenge. Performance and dialogue (“Boards don’t hit back”) is the focus here, especially since Wall sells all of Bruce’s kicks a fraction too late, but none of this detracts from the value of this scene in context of the story, let alone show off Lee’s impressive real-life fighting skills. Many would lay claim that Lee’s famous nunchaku battle later in the film is the real meat, but this scene really nails the almost mystical power that Lee holds as a performer as well as a man trained to turn his body into a weapon. People who want choreography and stunts may not be impressed, but this is one of the greatest martial arts fight scenes ever realized and thus deserves a place here.

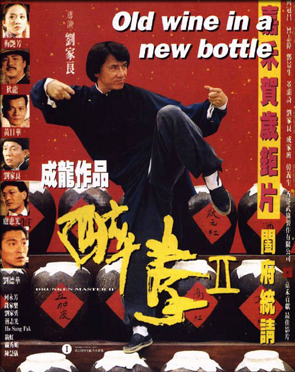

Wong Fei Hung vs The Bullies from DRUNKEN MASTER II

Finally we come to it. Drunken Master II. I don’t know where to begin, suffice it to say that while Fist Of Legend may be regarded as ‘THE best martial arts film’, this movie is regarded as having the best FIGHT SEQUENCES ever devised in the history of hand-to-hand combat. It really doesn’t matter which clip I stick on here – the duel in the fish market, the axe-gang attack, the epic showdown in the steel factory that has seen audiences all over the world lose their own jaws under their seats from repeatedly hitting the floor over and over again – every sequence in this movie is an astonishment. This movie is like a ‘Ripley’s Believe It Or Not’ of martial arts cinema. It’s the ‘sitting in a dark movie theater in 1977 and watching Star Wars for the very first time’ of martial arts cinema. It’s the only Kung Fu movie that you’d take your grandparents or your mum to with complete faith that they’ll have the time of their lives. The production stories alone are enough to draw you into the film; Jackie Chan doing handstands at the start of every shot to acquire his flushed ‘drunken’ complexion, the hundreds of retakes required to get astonishing stunts perfectly executed, the grueling FOUR MONTHS (that’s 120 DAYS) of shooting JUST for the final fight sequence alone! I don’t know what more to say other than this is it people. This film is almost 20 years old and there’s nothing – NOTHING – that can compare to what these crazy mofos put themselves to or managed to get their bodies to do in order to make us laugh, gasp and cheer. Aside from the astonishing physical feats performed, Drunken Master II operates as a brilliantly performed, high-slapstick, farce which sees the historical folk hero Wong Fei Hung (Jackie Chan) re-designed as a naughty, but brilliant, Kung Fu student who is constantly getting into trouble because of his penchant for alcohol and his abilities in Zui Chuan (Drunken Boxing). He becomes the target of harassment when he stumbles across an artifact smuggling operation, all the while being berated by his well-meaning father who thinks his son is a lay-about who is encouraged by his feisty and sassy step-mother (Anita Mui). In this scene, my personal favourite from the film, Fei Hung is harassed by thugs working for the smuggling operation who want an artifact that has accidentally become lodged inside his step-mother’s handbag. Just click play and get ready to have your socks blown clean off.

And that’s it.

I hope you enjoyed our very brief little jaunt through the history of martial arts cinema and you got a kick out of some of the clips. But really this is just the tip of the iceberg and one can only hope that the popularity of films like The Raid will see another resurgence of martial arts in modern cinema both in and outside of Asia.

What are some of your favourite martial arts films or fight scenes? I’d love to hear about them!

Thanks for reading.