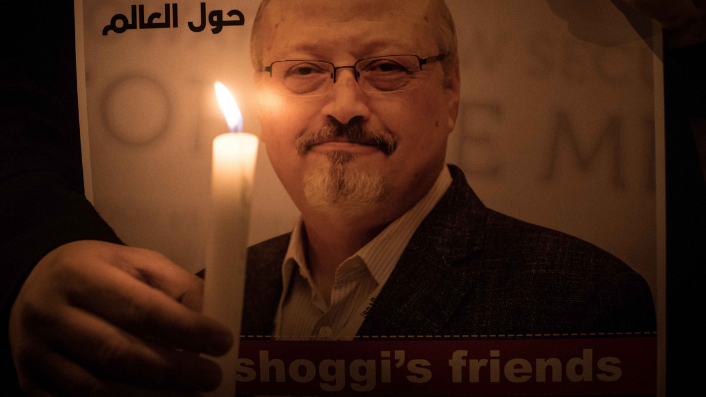

The Dissident director on the horrific murder of journalist Jamal Khashoggi

Bryan Fogel speaks with us about his follow-up to Oscar-winner Icarus.

The Dissident sees Bryan Fogel (director of Oscar-winning documentary Icarus) lay out the facts behind the horrific killing and cover-up of Washington Post journalist Jamal Khashoggi after entering Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul. Steve Newall spoke with Fogel about the importance of a human dimension in his retelling of a horrendous crime.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

FLICKS: I had a real sense of horror and disbelief as this story first unfolded. Do you remember your experience when you heard about it?

BRYAN FOGEL: I was following this story very, very closely. My desire to make this film started growing immediately as this story was breaking in the press—I had been seeking what that next project was going to be. At the time I had not heard of Jamal Khashoggi, and very quickly into my research here, I found this guy was a very, very prominent voice in the Middle East, a respected journalist.

See also:

* All movies now playing

* All new streaming movies & series

* The best movies of 2020

Not in life, but in his death, as the story was emerging to a global audience, he was no longer a Saudi journalist. He was a Washington Post journalist. And that differentiation made all the difference in the coverage of the story and ultimately why the world truly came to know of this story.

And, you know, I was riveted by it. I was shocked by it. And then my mind said, hey, I think this could be my next film, if I can have the participation of [Khashoggi’s fiancé] Hatice, if I can have the participation of [Saudi activist] Omar and gain their trust and the participation of the Turkish government. I set out over the next several months to try to gain those elements and lock in those elements that I saw were needed to craft a film.

After so much press coverage, how did you preserve the impact of the story, its capacity to still shock?

I was not interested at all in putting together what I deemed as an archival news story. And obviously, it would have been very easy to go, hey, I’m going to go pull tons of Jamal interviews. We’re going to pull this together, and we’re basically going to do a long-form, news-style thing on the murder of Jamal Khashoggi. What I was interested in was who was Jamal Khashoggi? What was he writing about? What was he standing up for? And what is the story, the untold story behind this murder that has the power to shock that as a power to make an audience go “wait, I thought I knew that story, yet I don’t”.

And that, to me, was the same journey that I went on with Icarus. I mean, here we had brought that story to The New York Times and people knew from the outset, oh, Russia had a state-sponsored doping system. They were cheating for decades. There was a scientist who was overseeing the programme, that was the boilerplate of it. And then when you watch Icarus, you go, oh, my God, there is so much more to this story. And you come to learn and love Grigory Rodchenkov and understand this for really what it is. That was my goal in coming into this story.

So Hatice and Omar were so pivotal to that, because I wanted to tell a story that was of the moment that really had real-world implications and also, hopefully, an audience could come out of the film with an emotional connection to Jamal. The only way to do that was to fall in love with Jamal. And the only way to fall in love with Jamal was to understand who Jamal was as a person and to see the impact that his murder had on the woman that he was going to marry. And on this young Saudi dissident, Omar Abdulaziz, who was not only carrying forward his work, but under great risk and danger to his own life as well.

It feels to me that the murder itself is an act of utter brazenness and impunity. The world knowing that they did it and how they did it, that’s kind of the point. So what part of the telling of Jamal’s story do you think Mohammed bin Salman wouldn’t want us to know about?

You know, I think what you see in the film and I think what is hard for a Western audience to fathom, is this idea that freedom of speech is not a given right in so many parts of the world. Simply speaking your mind can lead to death, imprisonment, murder, false charges, and you in New Zealand and me in the United States, we wake up every day and go, OK, if you criticise your prime minister and say “I disagree with what Jacinda is doing”, that’s not going to land you in jail if you write anything critical of your government.

In Saudi Arabia, not only do those rights not exist, to express those rights means the likelihood that you will face imprisonment or death. And for me, it’s why this story was so important.

I think what you see in your question of Mohammed bin Salman is this concept of, wait, here’s a guy who’s perhaps the richest man on planet Earth. We don’t know. But arguably, he’s a trillionaire. His family controls the entire wealth of that country. And yet with all this money and all this power, he still feels this incredible need to suppress any free thought or any opinion. And rather than be a magnanimous leader, a leader that inspires his people, he chooses to be a leader that lives in fear of revolution, in fear of revolt and fear of any critical judgement against him.

And this fear leads him to do things such as murder Jamal Khashoggi or imprison thousands and thousands of activists or journalists or writers or economists or anyone who has a differing opinion against him. And what I wanted to lay bare in the film are the lengths that he is willing to go to in order to suppress any sort of freedom of expression, freedom of thought, freedom of opinion.

In the hacking of Jeff Bezos’s phone, you see this act of revenge. In the takeover of Twitter, you see the complete suppression of free thought narrative. And in the jailing of Omar’s brothers and his friends —that are not even activists, that have nothing to do with anything other than knowing Omar—you see the revenge tactics that he is willing to go to, extreme tactics to silence freedom of thought and opinion.

It’s these sorts of behaviors that made me all the more steadfast in my resolution to tell this film. As you go on a journey with somebody like Omar there are moments of thinking “This is shocking. This is thrilling. Oh, my God, you just got a death threat as I’m through filming with you.” One side of you goes, “well, this will make for an incredible film,” and the other side of you goes, “Oh, my God, what is this world that we’re living in?”

Donald Trump seemed to look at these dictatorial figures with a lot of envy while President.

You know, under the Trump administration—this is why I’m actually glad that the film is coming out now rather than during his administration—there was zero chance that there was going to be any holding Saudi Arabia accountable. Not only that, Trump bragged about saving MBS’s ass. Clearly, there were very deep ties between his family, the Kushner family, the Saudi family, and his desire to exploit the friendship that he was carrying forward for financial gain, for business gain.

And he made it very clear that he wasn’t going to get let the murder of a journalist or jailing of human rights activists or anything get in the way of of the billions of dollars of business, tens, hundreds of billions of dollars worth of business to the kingdom.

There’s a sense Trump was almost jealous that other leaders got to do the things that he couldn’t do or secretly wanted to do.

I’m so happy that he is gone. You know, somebody who was willing to push the power of the presidency that we had never seen before in the United States We had never seen a president come in and basically try to do everything he could to change not only the nature of our democracy, but the system of which we hold our leaders accountable, you know. Obviously in New Zealand, you guys have one of the world’s great democracies. In the United States, we not only saw that under attack for the last four years, we saw the power of fake news, the power of social media.

And clearly, Donald Trump, if he had his way, would have liked to turn the country more into the style of Putin’s Russia and MBS’s Saudi Arabia or Kim Jong-un’s North Korea and or Bolsonaro’s Brazil et cetera, where a strong man, essentially a dictator, makes all the decisions and those that oppose him are sent away or locked up in jails or, as he implored his crowds to do, raid the capital, as he incited violence.