The legacy of Jane Campion’s The Piano, 25 years on

When, in 1993, Jane Campion’s film The Piano won the Palme d’Or at the Cannes film festival, the first film by a female director ever to do so, it must have seemed like the dawning of a new era. Sure, the moment was undercut by the fact that the win came as a tie – Chinese drama Farewell My Concubine also shared the prize – but the honour bestowed by this elite and prestigious community would surely have signaled that things were looking up: a long archaically gendered industry finally willing to break its own glass ceiling and welcome the idea of inclusivity.

Hanging heavy above The Piano‘s 25th anniversary, then, is that it remains to this day the only film to have achieved this feat, while Campion, having recently reemerged in the public consciousness with the success of TV drama Top of the Lake, can arguably count herself among a select few to have earned lasting respect and recognition as a much fabled female auteur.

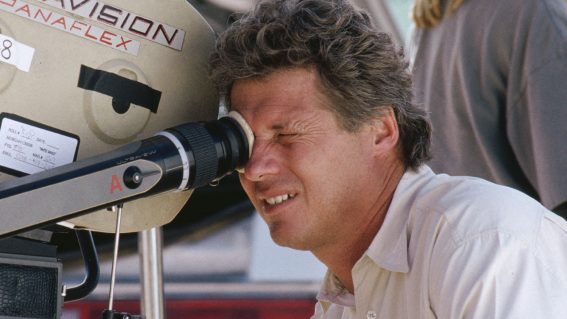

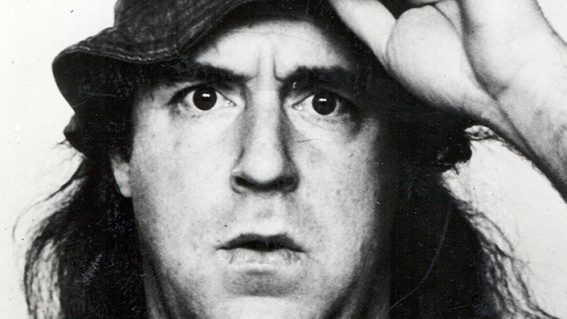

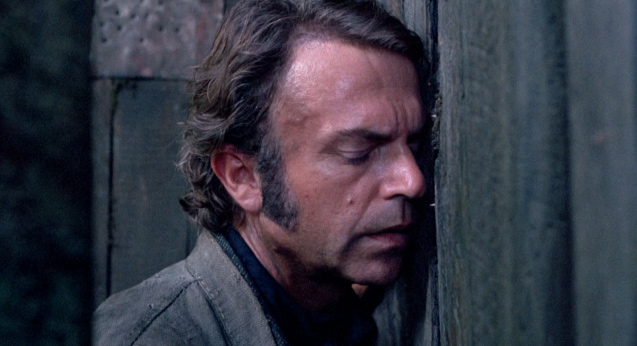

Taking place in the phenomenally bleak looking 19th Century, The Piano follows the stubborn, mute Ada (Holly Hunter) as she travels from Scotland to colonial New Zealand to enter into an arranged marriage, bringing with her an illegitimate daughter and a nice heavy Piano. Arriving on the black sands of Karekare beach Ada is devastated to find that her new husband Stewart (a fabulously frigid Sam Neill) isn’t super keen to lug the instrument home through the bush – instead selling it to local dude Baines (Harvey Keitel), a European ex-pat who has rejected imperialism and instead chosen to live amongst the local Māori.

Sadly for Stewart, he and Ada don’t exactly hit it off, a problem exacerbated by his extreme sexual repression and ill-advised habit of shouting at her like she’s deaf. Still pining for her piano, Ada instead becomes embroiled with Baines who offers to return it to her one key at a time – the price being that she must play for him while he does “things he likes” (things Baines likes: wandering around butt-naked and poking the holes in her stockings). Understandably charmed Ada and Baines quickly embark on an illicit love affair, which leads to a violent confrontation.

However you may feel about the wack-a-doodle colonialist love triangle, this grim love story struck a chord, receiving not only the prize at Cannes but four Academy awards. Replete with iconic imagery and permeated with melancholy with a strange, haunting soundtrack, what is perhaps most striking about The Piano 25 years on is how deeply Campion’s ruminations on women’s silence and artistic expression still resonate.

Years before we were all sick to death of hearing about “strong female characters” Ada was a pretty tough lady: Hunter, known for her unique and powerful voice, is only heard to speak by the viewer in a strange high pitched voiceover; her silence, though largely unexplained, is presented as being born of a kind of stubbornness. “No one knows why, not even me.” she tells us of her muteness. “My father says it is a dark talent, and the day I take it into my head to stop breathing will be my last.”

Instead artistic expression is shown to be Ada’s voice; her Piano, traded back and forth between the men her life, stands as a fairly obvious representation of her agency, and just as her father sells her to a stranger on the other side of the world, so too does a kind of bidding war emerge over the instrument that constitutes her voice.

In the past year, since the emergence of the Harvey Weinstein allegations and the ‘Me Too’ movement, the issue of women’s voices – and the devalued, trivialised and dismissed means through which they express them – has finally broken through into the mainstream to reveal a longstanding systematic displacement of female artistic expression.

Which makes it all the more frustrating to think that, a quarter of a century ago, Campion was incredibly unsubtle about any of this: A gothic melodrama, traditionally “women’s film” territory and therefore not likely to be considered of much artistic worth, The Piano is as dark, dreary and perverse as Jane Eyre, now accompanied by some rather grubby sex scenes. Ada’s plight, helpfully mirrored by an in-text performance of the Victorian folk tale Bluebeard, is a fraught power struggle for agency even when it resolves in romance.

As the industry finally acknowledges, and thus mourns, the loss of a canon of female work through the silencing, abuse and blacklisting of female creatives, The Piano‘s commercial and critical success is perhaps shown to be even more of an anomaly: an unapologetically feminine narrative, given tangible respect and recognition by a predominantly male community. Yet, what made The Piano‘s victories at Cannes and the Academy Awards so meaningful is also what makes the lack of women to follow in her footsteps so incredibly frustrating.

Of course, not everyone was a fan of Campion’s deeply politicised success. The portrayal of local Māori, who observe the goings on of the settlers like a kind of sassy Greek chorus, has long been considered by many as problematic, bordering on racist; Baines, as a white European appropriating their tattoos and language, an exceptionally glib figure in a story seemingly so concerned with expression.

Whether the film can even be truly considered feminist has also been a point of contention, most notably by the feminist writer and activist bell hooks, who, writing not long after its release in 1994, took particular issue with the uncritical reception the film had been receiving: “Reviewers and audiences alike seem to assume that Campion’s gender, as well as her breaking of traditional boundaries that inhibit the advancement of women in film, indicate that her work expresses a feminist standpoint”, wrote hooks. “And, indeed, she does employ feminist “tropes,” even as her work betrays feminist visions of female actualization, celebrates and eroticizes male domination.”

Ultimately concluding that The Piano falls short of qualifying as a feminist text, hooks argues that it perpetuates the idea that, for women, artistic agency can be reasonably sacrificed for heterosexual romance: and one which, in this instance, also happens to take place in a racist, colonialist setting.

It’s a solid critique and, in 2018, hook’s assessment still holds up – particularly as the importance of intersectionality becomes more and more understood in feminist discourse. And yet, given how few women have been afforded the opportunity to succeed her, it seems more the fault of the industry than Campion that the film is still used to so broadly represent female artistic achievement.

In the 25 years since The Piano was released, Campion has hardly remained inactive: From the poorly received (yet weirdly enjoyable) Meg Ryan noir In The Cut to the wistful romance of Fanny Brawne biopic Bright Star, to the wildly popular Top of the Lake, she has built a body of work that continues to examine women just as strange, stroppy and sometimes unsympathetic as Ada – yet only in recent years, with the success of Lake, has media attention turned back her way.

To see Campion newly beloved once again as a teller of women’s stories, so long since she was first thought to break new ground for female filmmakers, is bittersweet and yet not entirely disheartening. The anniversary of The Piano, celebrated by the release of a restored anniversary edition and cinematic screenings internationally, is an opportunity to re-consider not only an iconic text, but the legacy of a female filmmaker who has, as of yet, been robbed of successors.

This story is part of our month-long celebration of 40 years of NZ film. Follow all our daily coverage here.