The Spider-Verse movies propose a different language for superhero stories

Imagine how much more inventive the superhero trend would be if we got the mind-boggling Spider-Verse movies a bit sooner: Luke Buckmaster hails them as “spectacular exceptions” to their genre.

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse

Spider-Man: Across the Spider-Verse isn’t as zesty and zippy as its predecessor, Into the Spider-Verse—a cheerfully invigorating superhero story that turned timeworn tropes into poppin’ fresh spectacle. But it’s still a blast to see this emerging franchise (which has a third film on the way) do something the MCU outlawed a long time ago: be visually interesting.

If a cinephile were asked to name a popular film movement of the 21st century, most would probably respond: “superhero movies.” This proliferate and massively popular genre is a movement in content and volume, not form or style. Whereas other key movements in cinema (noir or German expressionism for instance, to name just a couple) have unifying aesthetic principles, the archetypal superhero production is just nondescript CGI-sheened flapdoodle, devoid of distinguishing features. And no: goofy costumes don’t count.

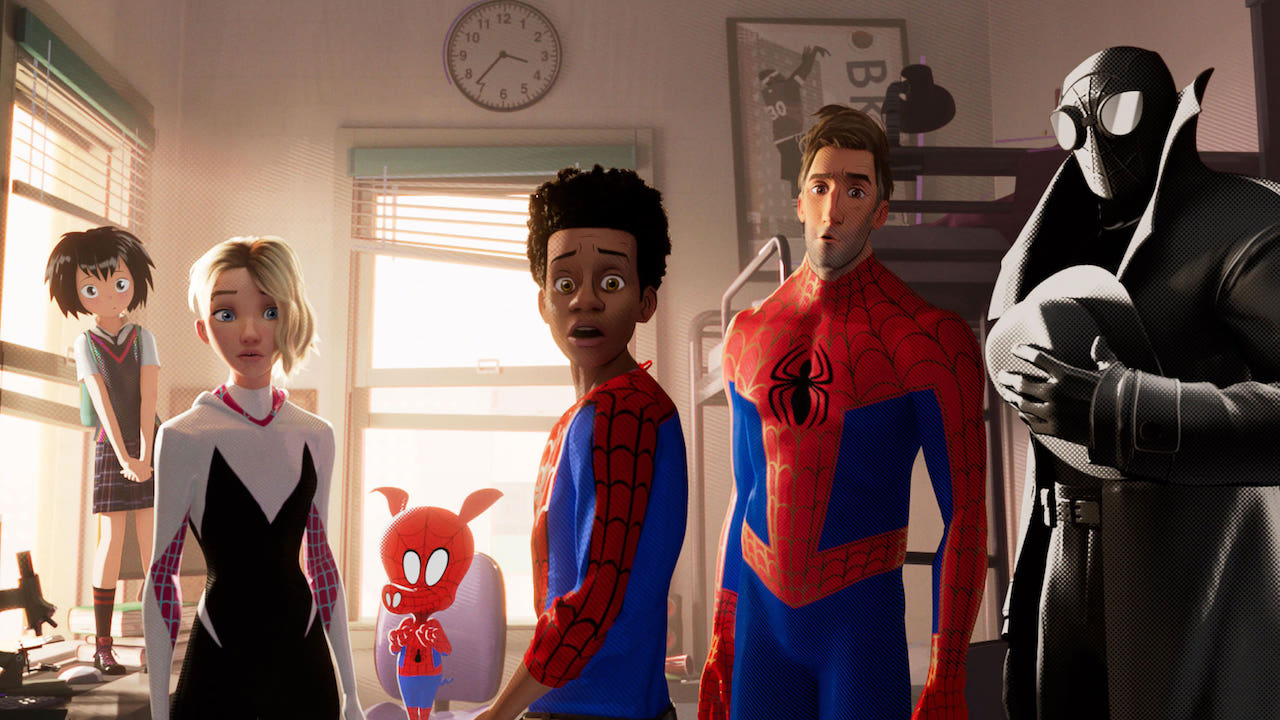

The Spider-Verse films are spectacular exceptions. Both follow the story of Miles Morales (voice of Shameik Moore), an NYC teenager who is Spider-Man, Spider-Man, and does whatever a spider can. So is Peter Parker, Miguel O’Hara, Pavitr Prabhakar, Gwen Stacy (well, Spider-Woman) and Peter Porker (Spider-Ham), as well as many, many others. They are all iterations of the iconic web-slinger, belonging to different worlds tumbling around distant regions of an unfathomably large multiverse.

The existence of so many Spider-Whatchamacallits, and so many worlds, implies a kind of cosmic chaos: a mess of discordant narratives stretching out for infinity. And yet the Spider-Verse franchise is big on fate and predeterminism. Especially Across the Spider-Verse (directed by Joaquim Dos Santos, Kemp Powers and Justin K. Thompson), which tosses around the idea, in a major plot thread, that while the Spidey universes are wildly varied, each share particular “canon” events. Messing with these events equals disrupting the fabric of the universe—which of course the protagonist knowingly does, as part of his efforts to save a loved one.

The Spider-Verse films contain two key visual features that distinguish them from garden variety superhero flicks. And which, in another universe (multiverse?) might have been widely shared across the genre and given it a more established, coherent style. The first is the trippy idea that each Spider universe has its own aesthetic principles, which continue even as parts of one cross over into another. In the original, for instance, Spider-Man Noir can only see in black and white and has a dusty monochrome appearance; in the second, the too-cool-for-school Spider-Punk resembles a human-shaped Sex Pistols album cover.

When we imagine out-of-this-world things—like aliens or characters from another reality—we tend to envision them using the shapes and forms of our own. These films suggest that’s a failure of imagination—because things from other universes don’t necessarily adhere to design principles from our own—while paradoxically drawing on pop culture inspirations firmly entrenched in the earthly zeitgeist.

The other key visual feature, baked into the DNA of comic book stories, are comic book panels: reduced fields of representation, referred to in film as split-screens or frames within frames. It takes just seconds for each Spider-Verse movie to kick their screen-slicing off with a horizontal split: the first of many panel-like displays across their runtimes. The original even has a scene in which a nervous Morales, contemplating his new super-abilities, opens a comic book and consults it for inspiration, as if it were a religious document (which in this world it kind of is). He observes a picture of Spider-Man atop a building, looking down, telling himself “you just gotta do it.”

It’s odd that frames within frames didn’t become more of a thing in superhero movies, given how crucial, how inseparable they are to the comic book experience. One of the most significant—and sadly overlooked—Marvel movies is Ang Lee’s 2003 film Hulk, which, with its inventive use of split-screens and transitions, proposed a blueprint for how superhero movies could have a unique cinematic style. Perhaps if the film had been better—without hammy performances, waffling dialogue or a dawdling pace—it might’ve had more of an impact.

At least we ended up getting the Spider-Verse films, although they arrived very late—like someone rocking up to a house party with an unopened bottle of spirits in the early hours of the morning, when everybody else is blotto. Imagine what impact these movies might’ve had, if they’d arrived much earlier. As they say: better late than never.