Welcome to Marwen is an under-appreciated film about creation

With Robert Zemeckis’ new movie Here now in cinemas, we thought we’d republish this piece about his 2018 curio Welcome to Marwen (first published in June 2019) which Luke Buckmaster says is under-rated.

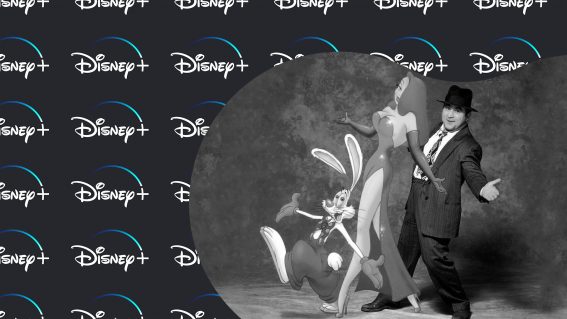

What’s better: to shoot for the stars and attempt the creation of bold, unorthodox, outré art, or to remain mollycoddled in formula—staying safe, conventional and indistinct? Consult any number of cookie cutter superhero movies for examples of the latter. For a more ambitious film you could do a lot worse than director Robert Zemeckis’ surreal character study Welcome to Marwen, starring Steve Carell as a real-life artist who escapes the pain of his existence by retreating into a play world of dollhouse-sized buildings and figurines.

The film tanked at the box office and didn’t make much of a splash on home entertainment platforms. It’s a film about creation: of the real and the imaginary; the small and the large; the literal and symbolic. Hogancamp, who is played in a mopey, stoner-like manner by Steve Carell, is the god of his little fantasy universe, where a mini-me doll version of himself, named Captain Hogie, and a gang of arse-kicking women fight off attacks from Nazis.

The context for this imaginative playground is intensely melancholic. The artist suffered severe brain damage after being beaten to within an inch of his life by a group of men, after drunkenly mentioning his affection for wearing women’s shoes. Co-writers Zemeckis and Caroline Thompson make an interesting connection between mental illness and artistic endeavour, contemplating how deep psychological scars can be alleviated through flights of fancy. It’s complicated territory, involving the celebration of things born from great sadness.

The visual design of the animation, chunks of which are strewn throughout the runtime, is too smooth and gloss-lacquered, continuing the director’s less than stellar record in the animated space—following the strangely lifeless aesthetics of Beowulf, The Polar Express and A Christmas Carol. These highly energetic moments nevertheless have a chaotic force behind them; a real oomph. They are bursts of fantasy that cannot be divorced from reality, given their complicated genesis and psychological roots.

The film opens with full-throttle action: Captain Hogie (who was modelled to resemble Carell) is high above Belgium during WWII, in a fighter jet, navigating a chaotic skyline pockmarked with blasts and explosions and bursts of smoke. This conventional wartime moment turns bizarre when Hogie crash lands, slips on some high heels, then is attacked by Nazis. We later realise that this moment captures Hogancamp’s real-life experience, a strange and interesting recreation less concerned with what happened than how it felt.

Zemeckis then switches realities, showing a giant (for the miniature world of Marwen) paint brush making an adjustment to Hogie’s face. He introduces us to the real Hogancamp, who’s fidgeting with the very scene we just watched and taking photos of his micro tableau. Later, on occasions when reality becomes too much for the protagonist (such as a scene in which a jittery Hogancamp listens to an answering machine message about an impending date in court) the fictions of his mind take over and bring him back to Marwen, which is as much a place as a state of mind.

Visually representing mental illness is difficult terrain at the best of times, let alone with everything else involved here—including the idea that terrible things can lead to beautiful outcomes. Several reviewers unfavourably compared Welcome to Marwen to the low-fi documentary Marwencol, which explored, with loving attention to detail, the real-life artist and his impressive works. But I thought Zemeckis was thoroughly respectful in the extrapolation of the themes apparent in Marwencol, and in Hogancamp’s own life, even if Welcome to Marwen ultimately feels too cute and composed.

It’s fascinating to contemplate what a different director, like Terry Gilliam, might have brought to the material, given Gilliam’s intense hallucinogenic style has so strikingly explored mental illness and the boundaries of reality (in Brazil and The Fisher King particularly). His vision would look scruffier, for starters, and that scruffiness would influence other aspects, perhaps feeding into a braver exploration of the darkness and demons inside Hogancamp’s mind.

But still: Welcome to Marwen is a bold film; a compelling film; a film that finds beauty in its imperfections. Given the extent to which multiplex cinema is being pummelled by established IP and air-headed spectacle, the fact that a major studio (Universal) would even get behind an ambitious project like this feels almost like an act of defiance, if not bravery. Forget the film’s measly 33% Rotten Tomatoes approval rating. There is much to appreciate.