Twenty years on, Oldboy remains a ridiculously watchable blast of nihilism

As Park Chan-Wook’s Oldboy turns 20, it returns to select theatres, restored and remastered in 4K. Tony Stamp revisits the entertaining and stomach-churning modern classic.

The early 2000s were a magical time for online movie chatter. The industry began to feel less siloed: if you knew which site to visit, you could start to hear about all manner of films from outside traditional distribution channels.

This was most immediately apparent with regards to international pictures. Suddenly, alongside excited write ups about Raimi’s Spider-Man, you could get advance word about the next effort from an acclaimed Korean genre head.

Park Chan-wook had several movies under his belt already by the time he put out Sympathy for Mr Vengeance (a few of which he’s disowned). But that title gained traction on Western sites thanks in part to its unrepentant violence and subject matter; falling into a ‘you won’t believe how far it goes’ kind of category that was appealing to a certain type of movie nerd. Myself included.

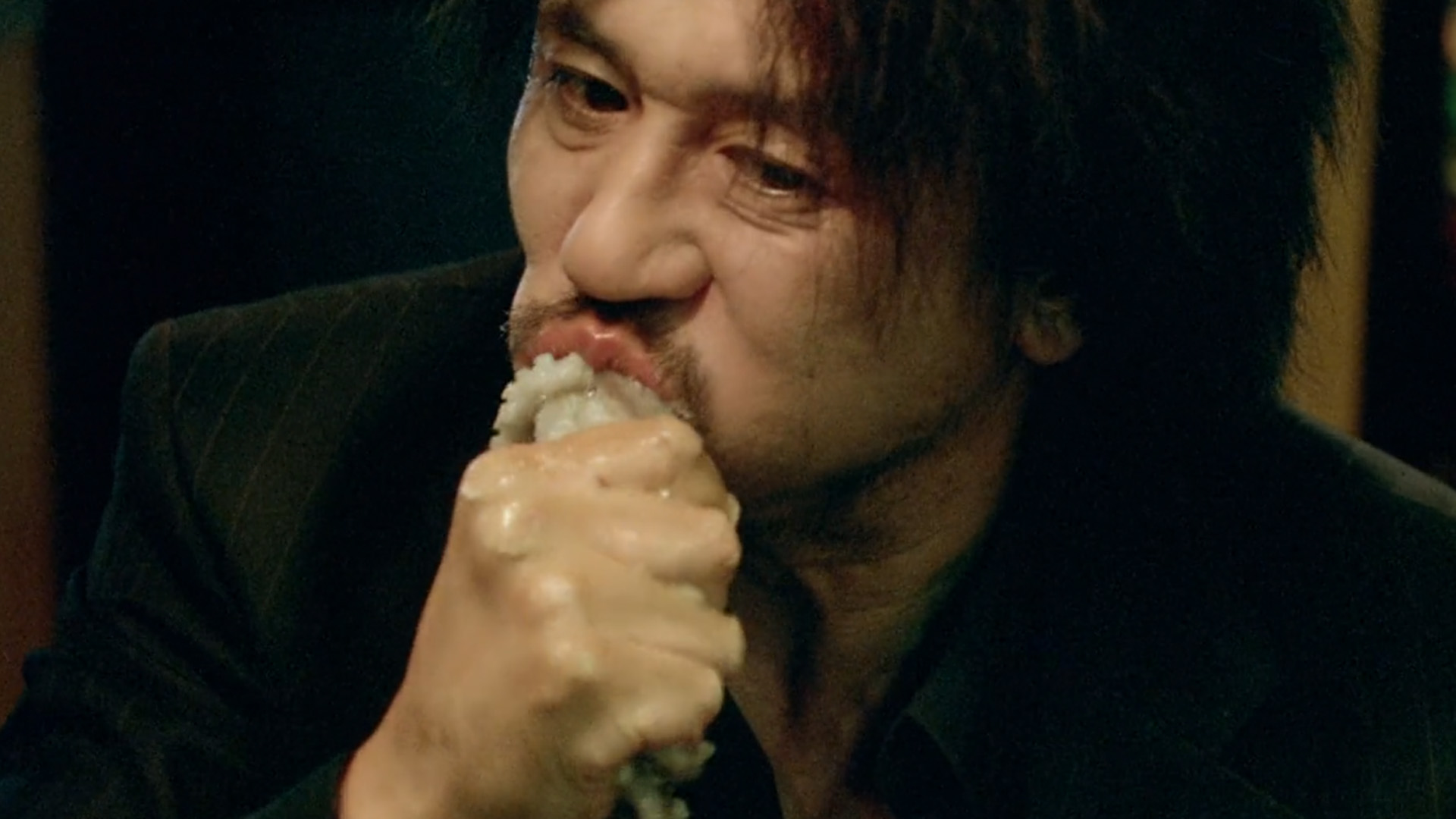

When buzz about his follow up, Oldboy, began to circulate, it was in a similar vein. Whispers about a live octopus being eaten, and a gruelling hallway fight did the rounds, with hints of even more salacious plot turns at the film’s end.

Once it arrived, the movie delivered enough carnage to satisfy edgelords everywhere, alongside more elegiac sequences that lit a fire under budding cineastes, and signalled what was to come from director Park.

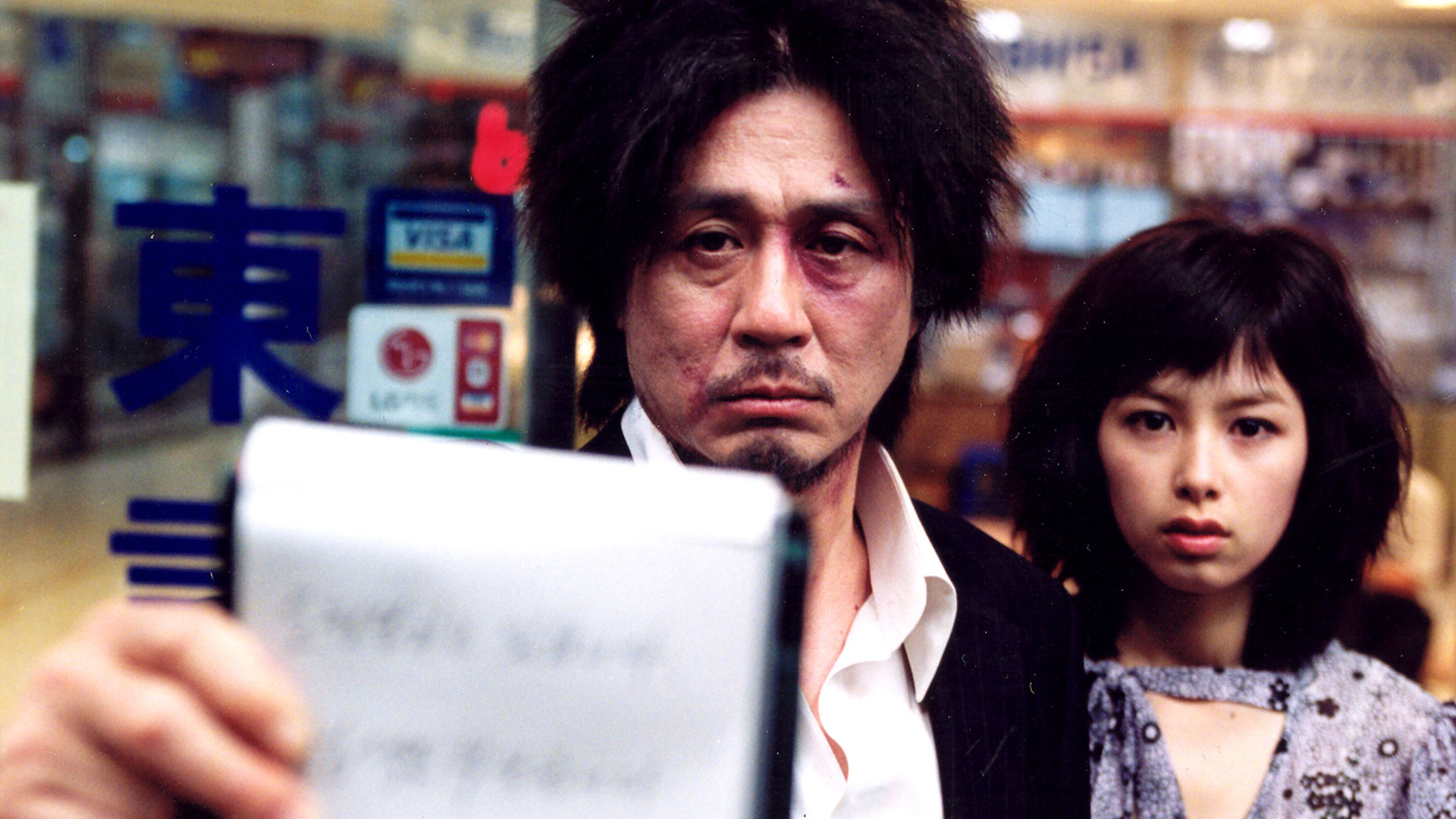

For the uninitiated, Oldboy concerns a businessman called Oh Dae-su, introduced while being detained for public drunkenness, who upon his release is spirited away by faceless captors and imprisoned in a hotel room. His voiceover quickly tells us he will be there for fifteen years, with no human contact apart from the hand that shoves dumplings through a pet door once a day.

The room contains a television, on which he sees his wife has been murdered, leaving him the main suspect. He has no way of knowing what has become of their four year old daughter, and after years of despair, devotes his time to physical training (a lot of wall punching), and focusing his mind on revenge.

Once released, he’s hellbent on finding out who did this to him, and why (as well as why they let him go). It’s a hell of a set-up, and rewatching for the umpteenth time I remain impressed by how nothing pans out quite like you think it will.

The infamous hallway fight, where Oh Dae-Su batters a horde of goons, actually feels more impressive for how it moves between sloppy, chaotic fist-swings and highly choreographed punches; thrilling while making clear no one involved is actually much of a fighter. Apparently the idea to do it in a single unbroken shot was star Choi Min-Sik’s idea. It took seven takes to complete.

The scene where he eats a live octopus took four, and similarly, is more stomach-churning than I remember. Choi, a buddhist and vegetarian, said a prayer before each take.

It’s notable that the violence is relatively bloodless (the gnarliest moment is a tooth being removed with a claw hammer, and even that doesn’t show as much as you might remember). And after all this edgy table-setting, all the moments that 20-something me found so compelling as I dared myself to sit through them, comes the third act, and that’s when things get really grim.

I won’t spoil it here, but there’s a twist, and it’s a doozy, Park relishing its slow reveal as much as the villainous Lee Woo-jin does. Watching this revelation as a younger man was mildly discomfiting; in my 40s it was incredibly upsetting. There’s a moment involving an audio recording that’s surely one of cinema’s sickest jokes.

And then the film keeps going, and director Park begins to hint at how his career will progress: operatic flourishes, kink, the treacherous nature of memory; all things that would come to characterise his output.

Oldboy was adapted from a Japanese manga of the same name (and from the sound of things, differs pretty drastically), and is still the most heightened of the filmmaker’s output. His attention to design and composition was immaculate from the get-go, and would reach new heights in movies like Thirst and The Handmaiden, but visual touches like Oh Dae-su’s thatched hair and the blonde locks on Lee Woo-jin’s silent sidekick are genre nods, not to mention the way shots sometimes transition as if they were comic panels.

The pace of storytelling is distinct also, whipping through scenes and daring the audience to keep up, with a manic edge that would fade as the director aged. The era-appropriate electronic score would go too, but the swooping classical strings would stay.

The film owes a lot to its lead, with Choi Min-Sik embodying its unhinged energy in a performance so committed it’s occasionally hard to watch. In the opening scene, which takes place before Oh Dae-su’s kidnapping, it’s genuinely hard to tell it’s the same actor. He’s fearless.

On rewatch I was almost as impressed with Yoo Ji-tae, who, in the final stretches, gets to show a more sympathetic side to Lee Woo-jin. He’s convincingly moving, even after enacting one of the most diabolic plots in all of fiction.

Twenty years on, Oldboy remains ridiculously watchable, entertaining no matter how many times you’ve seen it. Park Chan-wook would mature, and mellow, and make more considered pictures. But this blast of nihilism is still unbelievably bracing.