Understanding The Dude: revisiting The Big Lebowski’s gloriously kooky characters

Twenty years after The Big Lebowski first arrived in cinemas, critic Luke Buckmaster revisits this inimitable comedy to see what makes it tick.

Happy birthday, Dude! Twenty years after The Big Lebowski first arrived in cinemas, critic Luke Buckmaster revisits this inimitable comedy to see what makes it tick.

Many words have been written reflecting on the Coen brothers’ 1998 comedy classic The Big Lebowski, which returned to cinemas this year to commemorate its birthday. It is now two decades since El Duderino took up residence on the soiled rug of popular culture. The film’s success is a case in point for the “hard lesson” of film history, as espoused by the great critic Andrew Sarris: that “the throwaway pictures often become the enduring classics whereas the noble projects often survive only as sure-fire cures for insomnia.”

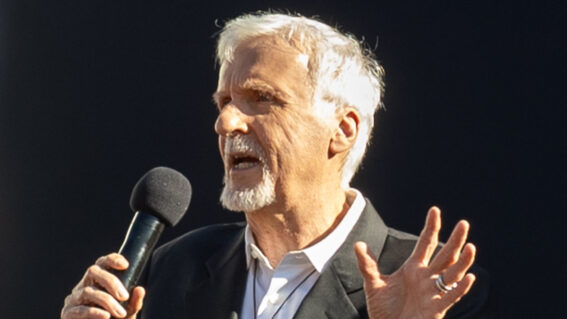

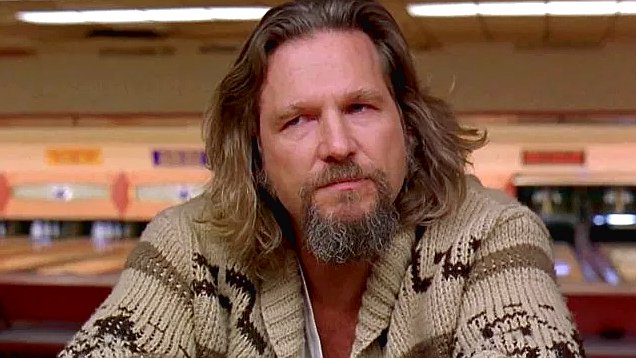

I thought a visual analysis of the film’s dream sequences might be fun to write about for its birthday. Quotes from The Big Lebowski have spread like wildfire and articles reminiscent of the beginning of this one, reflecting on the film’s legacy, are a dime a dozen. But what about those fabulous moments of high-flying fantasy? Who could forget Jeff Lebowski aka The Dude (Jeff Bridges) floating around in a bowling alley in space to the tune of I Just Dropped In to See What Condition My Condition Was In? Why isn’t anybody writing about them?

Upon rewatch I may have discovered why. These scenes felt too giddy to intellectualise; too pure to second-guess; too naively amusing to interrogate. What could I say that would enhance the reader’s appreciation of them? Discussion of visual motifs and the like felt pompous, like trying to construct a hypothesis out of nothing.

I decided the exercise was folly so I changed tact, struck, instead, by the crazy righteousness of the characters and their tenuous interpretations of morality. I don’t know why my mind went in this direction now and never before, but I couldn’t get it out of my head that the characters’ insane ideologies and kooky attitudes towards right and wrong play a significant part in why the relationships between them are so amusing, and why the plot is able to keep spiraling off in unpredictable directions.

Take, for example, everybody’s favourite character – the washed up hippy and White Russian connoisseur The Dude – and the action that triggers the film’s ‘in over his head’’ plot. The Dude is naturally incensed when goons break into his house and urinate on his rug, mistaking him for another (far wealthier) person also named Jeffrey Lebowski. Instead of pursuing the perpetrators, what does he do? The Dude tracks down the actual Jeff Lebowski – an elderly man in a wheelchair – and asks him for compensation.

Think about that for a moment. The protagonist blames the intended victim of a crime for…what exactly? Existing? Being wealthy? Being a target? The ‘real’ and ‘big’ Lebowski – a politically conservative self-made man – is understandably upset, ranting about how people should pay their own way and that he is not responsible “every time a rug is micturated upon in this fair city.”

For a while he appears to be reasonable but Lebowski’s swinery is later revealed, having given The Dude an empty briefcase he says contained ransom money – which he pocketed for himself. In the old man’s head, The Dude’s lecherous no-goodnik lifestyle has made him fair game.

Then there’s Walter, John Goodman’s violent and volatile loudmouth. Oh Walter: the kind of guy hilarious to watch in a film and a nightmare to be around in real life. During a bowling game, convinced a competitor stepped over the line, Walter goes ballistic and likens the situation to serving in the Vietnam War. “This is not ‘Nam, there are rules!’” he shrieks, retrieving a handgun from his bag – which he points at the competitor’s head and screams “HAS THE WHOLE WORLD GONE CRAZY?”

Indeed, yes: this is an insane universe full of mismatched people, each believing they are the heroes of their own narratives. The Coens evoke the old maxim ‘to the crazy person the normal person is insane’. The rest of the characters include a group of nihilists, a head-in-the-clouds conceptual artist and feminist (Julianne Moore) and two supporting characters – Lebowski’s PA (Philip Seymour Hoffman) and The Dude’s friend Walter (Steve Buscemi) – who are so awkward and introverted their timidity comes across as a form of craziness, or something close to it.

Let us not forget that The Dude, while charming, is a pathetic figure – shamelessly selfish and self-entitled. We love the idea of him more than we love him. If The Big Lebowski weren’t such a shrewd piece of work – with a keen sense of the absurd, and great affection for its unusual characters – a similar description might have applied to the film itself. Thankfully that is not the case. Instead, as always, The Dude abides.