Vivarium director on how his sci-fi blends housing crisis and The Quiet Earth

Vivarium director Lorcan Finnegan talks to Steve Newall about his surreal suburban sci-fi nightmare.

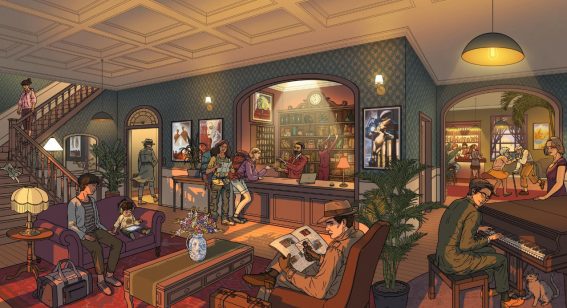

Vivarium sees a young couple (Imogen Poots and Jesse Eisenberg) looking to buy a home together, find themselves trapped in Yonder, a bizarre housing development full of identical family residences. In the country for screenings of his film at the NZ International Film Festival, Lorcan Finnegan told us more about his intriguing film, the horrors of housing, The Quiet Earth, and his experiences with Nathan Barley and Charlie Brooker.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

FLICKS: Is the lifestyle sold in Vivarium where you see us going or are we already there?

LORCAN FINNEGAN: I think that’s where we are. Except it’s just a little bit more exaggerated to highlight the absurdity of it. So it was kind of us taking the way we live already, more or less and just kind of amplifying it up so that you can see how weird it is.

You mentioned a housing crisis back home in Ireland during last night’s Q&A. Is it the same as here, where capital has been sequestered away by the wealthy and everyone else is a bit fucked?

Yes. Basically, a massive divide, and there’s whole entire families living in hotels. I listened to a radio interview recently and they were talking about how that may seem like a nice proposal, “Yeah. We live in a hotel,” but a whole entire family in one room after a few weeks it’s going to start getting chaotic.

Our government was paying for people to live in motels.

Yeah. But why?

Because people were living in cars. Families were living in cars.

Buildings are left locked up because people are waiting for the right time to sell them because they’re waiting for the market to pick back up and there aren’t compulsory purchase orders put in place by the governments and there isn’t enough affordable housing. Housing’s just become this thing that you can’t actually buy a house. You have to be really rich.

I think you might’ve described it as an obsession last night. It’s definitely an obsession here. There’s a conversation earlier in the film, I think it might be with one of the parents at the school about the market…?

Yeah, she’s saying, “The market’s going through the roof. You should really jump on it now.” And Gemma [Imogen Poots] says, “Oh, we’re going to go and see the estate agents later.”

That sort of exchange fills up so much space in everyday conversation.

Yeah. It’s a real obsession in Ireland, owning property. The idea of land ownership and all of that kind of thing. It’s strange. It’s just a mindset though because the Spanish live in apartments and rent their entire lives and that’s not considered strange and things are more affordable. I mean, obviously, the same thing happened in Spain. It’s a bit of a mess there as well and Greece. But yeah, the housing crisis really is an ongoing thing.

We made Foxes, a short film, in 2010 roughly but the time it was finished was 2011 and that was already reacting to something that was happening around 2005 which was just increasingly just getting worse. And since making that, made another film, Without Name, which is sort of about a property developer as well. It’s very different, about a guy who’s a surveyor who’s sent out to measure a piece of forest for a shady developer and the forest has a kind of spirit that protects it from this person and it gets psychedelic and weird.

And then by the time we came around to doing Vivarium, which we’d been working on for a few years just between things and gradually building the script up, it was all back again. We’d come full circle and it’s the exact same problems all over again. So within the film, the film has this kind of cyclical arc to it. It opens with footage of birds that have that kind of lifecycle as well and it seems that we just keep on repeating the same thing as well. It’s the cycle of strangeness.

My partner made an observation about the film, which was when you take away the contemporary issues it’s a very bleak analysis of what it means to be a family or what your purpose in life is.

Yeah [laughs]. That’s the existential dread part [more laughs].

How’s your existential dread?

I don’t know—we were just tapping into the anxieties of young people to kind of shake them up a little bit. That was an intention. I remember when we started into the script we were thinking what is it that scares people in their late 20s, early 30s these days? What is it that actually scares them as opposed to some sort of big monster? Godzilla was a product of the fear of atomic energy or nuclear war.

We were trying to coming up with a version in a stranger way of a monster, like the estate agent who would lead you to your doom. And people have this anxiety of moving to the suburbs and getting kind of trapped there and losing all sense of purpose and their life just sort of dwindling away while they repay the mortgage.

You had quite a sort of negative slant on the concept of mortgages.

Yeah. That you just pay it off until you die.

Right, you can just dig that hole. Just dig that hole, keep digging that hole.

Yeah. Dig the hole. Yeah. Keep on digging. Yeah. I mean to me it’s a big sick joke—the film—in a way. I don’t think it’s necessarily saying you shouldn’t do this, it’s just sort of highlighting how odd it is that we do it and that it’s not a necessarily the only society possibility. There’s other versions, other outcomes could happen. The little girl at the start of the film, Molly—she says she doesn’t like the way things are. So she’s like hope for the next generation.

Your casting of the other child that arrives in Yonder is amazing and you make some really interesting choices of what barriers you present to the audience to make us not really sympathise with the kid. Particularly the modulation of that voice. That voice is fucking weird.

It was written as being weird. A weird kind of mimic of them but not quite right. And because he doesn’t have anybody else to copy, it’s kind of a hybrid of voices and we did have to dehumanise him because the real kid did sound quite sweet. He had a lisp as well [laughs]. He’s brilliant.

So we edited the film with the real kid’s voice and were just thinking about ways of what we’re going to do. And then we had the idea – myself and the editor – that what if we use Johnathan Aris as the voice of the kid because he’s the first estate agent that comes in. And so we got him in to do a little demo and he just did a few lines. And it really worked. It was really weird but it worked. It wasn’t quite right yet but we thought, “Okay. That’s what we’re going to do. when we finish it.” So then when we did we got him in for a whole day and he did the entire film as ADR and then we spent a lot of time in Denmark with the sound mix designer and tweaking that and kind of shifting the pitches and syncing it to his lips and adding in little bits of the little boy on either end of the word like coming in and coming out accenting his lip smacks so that it would sit into his mouth more. It was really tricky but I think it was worth the effort.

I was thinking about how the uniformity of the town of Yonder must have been a real advantage when it comes to shooting. Did you go into this going, “This is great. We’ve got all these advantages because we know we can just reverse this and do that and….”

No. No. It was more like a terrible nightmare [laughs]. It’s like being dropped into this thing where you’ve got barely any time to make the film and this is all you have to make what you thought was going to be much bigger. Yeah. It was pretty stressful. It had all been storyboarded and planned a certain way which all had to change there and then with the clock ticking. Actually, on the very first day, there was a power cut because they hadn’t got a generator in Belgium. They were going off the local power and this massive warehouse—there wasn’t a sound stage—and, yeah, the power went for half a day. So we lost half a day the first day which meant the whole schedule was messed up and the storyboards were no longer viable for what we had to shoot. So we had to figure out how to rearrange shots, minimise the amount of coverage to be able to shoot the scenes.

So much is unseen in the film and that really works to the advantage of the audience. Was it a limitation thing for you or did you know that you could make it more interesting that way?

We thought about showing how the whole thing works and all that. We do have our version in our heads, how it all works underneath and the whole lifecycle of these other things. But I found it more interesting to just give little bits of it than show it. What we’d show wouldn’t be as good as what you’d imagine anyway, probably.

I guess it helps if you are on the same page, that you have a bit of architecture in mind.

Yeah, exactly. You know what the rules are to the place and all that kind of thing. Like with the weird fluffy clouds. It took people quite a while to get on board with that [laughs]. I was like, “No, it will look good.” And it needed that sort of storybook aesthetic to me anyway, that it’s this sort of surrealist painting, being trapped in that world. Do you remember The Witches—the Roald Dahl film that Nick Roeg directed—and there’s the little girl who’s trapped in the painting by a witch? That had some sort of profound effect on me when I saw it, it looked really creepy to be trapped in something that looked like a painting.

You mentioned The Quiet Earth last night and so I have a parochial responsibility to ask what resonates for you with that film.

Well, actually the last sequence part of Vivarium was inspired by that. And also just maybe some of the kind of crossfading or aesthetic. I know it was ’85 or something like that but it had a sort of 70s vibe to it. And the quantum strangeness of The Quiet Earth… Vivarium has that quantum element, things shifting and changing and loops and kind of thing. And the idea of being alone in kind of suburban environments, with nobody else. When we were in development, we were watching everything—all those sci-fis that dealt with similar themes and we really liked The Quiet Earth. The Quiet Earth was great. Very good performances all and the lead character just being a normal-looking guy which they used to do in the past instead of these kind of Gillette models.

So this film was obviously, a very difficult process for you. How do you feel about doing more at this point? Did you get PTSD from this experience?

I actually probably did for a while, yeah. But yeah, it’s a weird masochistic compulsion. You make a film, you go through agony and then when you finish it you just want to go and do another one. But the next one is potentially less complicated. A little bit more in the real world with elements of the supernatural, and then another one that is a little bit insane, with a location that’s augmented to extend it and make it into sort of an environment but not creating an entire environment. The tricky thing with Vivarium is it always had to have a certain vibe to it and for Yonder to have no wind, no rain, artificial light, and feel very synthetic but at the same time tangible. So I don’t think they’ll be doing another one with quite as limited kind of environment to create and build. Not for a while anyway.

I threatened to bring up Nathan Barley when we first sat down It feels like an increasingly prescient kind of work. I think sort of an amalgam of sort of cynicism and futurism. What did you take away from your time working on that show and just around Charlie Brooker projects in general?

I mean I wasn’t really on Nathan Barley. I went to set a few times and I had to dress up as a lampshade in one episode. Actually, I think it was the first time seeing a director working. It was Chris Morris directing that. I remember he was closing his eyes for a while, thinking about the scene, then he was like, “Okay,” and then got stuck into it again. I thought that was really interesting.

I did do graphic design in college but I kept on doing narrative work and things. I don’t know why, I just kept on doing things were sort of sequentially telling a story. And then when I was working with those guys, we got hired to make the first mobile video content for video phones that had to come preloaded with content. Charlie’s company had won some sort of contract to make comedy for these phones, both live-action, and animation, but they had tiny budgets. So we were a team of two writers, a designer, an animator, me, and a producer and we had to make all this stuff. I was just supposed to be a runner and then I started editing with them and then we were shooting and then I’d go and have to do some stuff on Nathan Barley and other shows that the production company were doing.

But I ended up having to make a lot of these live-action comedy sketches and be in them—act in them, shoot them, and edit them, and all that kind of stuff—which was cool because it was like going back to college again, but now making films and doing the kind of opening graphics and all that kind of stuff. So it was a great experience. And nobody saw it anyway [laughs]. I was sent on a course to learn how to use PD150. It’s a little Sony mini-TV camera, and that was that. Got really into making stuff and editing it and all that kind of thing. Good fun.