We almost forgot how good John Lithgow is at being evil

Lithgow demolishes his psychopathic role in The Rule of Jenny Pen, sporting gnarled fake teeth, eerie blue contacts, and an impressive New Zealand accent.

James Ashcroft’s retirement home horror The Rule of Jenny Pen is powered by great performances, writes Tony Stamp. Amongst them is John Lithgow, who reminds us how good he is at being evil.

There’s a shot in Brian De Palma’s 1992 movie Raising Cain in which John Lithgow smirks villainously, changing to a look of innocent surprise when another character turns in his direction. It’s a delicious bit of acting that seems to have stuck with James Ashcroft, as the director’s second film bases itself around Lithgow spanning these two modes.

He’s a big name to be gracing a New Zealand production, and is on a bit of a tear lately, with a string of acclaimed performances including the Oscar-nominated Conclave. Joining him in The Rule of Jenny Pen is another big name, the likewise much-celebrated Australian actor Geoffrey Rush.

Rush has been absent from stage and screen for the past few years, and this is a welcome return. In fact, it’s easy to see why the script would have appealed to both actors. They’re given monologues to sink their teeth into, life-or-death stakes, even action scenes, as well as rich, distinct characters. And all within a horror movie set in a rest home.

Rush plays Stefan Mortensen, a veteran judge we meet handing out a sentence in court shortly before he has a stroke and collapses. Sent to convalesce, Rush performs both Mortensen’s physical ailments and his misanthropy with typical commitment. He’s prone to bloviating and dislikes most people he meets.

Despite that, it’s hard not to feel for him when he starts being bullied by Lithgow’s Dave Crealy. When their mutual dislike turns into a game of cat and mouse, Mortensen’s struggles grow as the ongoing effects of his stroke continue to manifest.

Seeing Lithgow play a villain again is such a huge pleasure. He played several for De Palma (in Obsession and Blow Out as well as Raising Cain), but since then has proved so delightful in lighter comedic roles you may have forgotten how incredibly good he is at being evil.

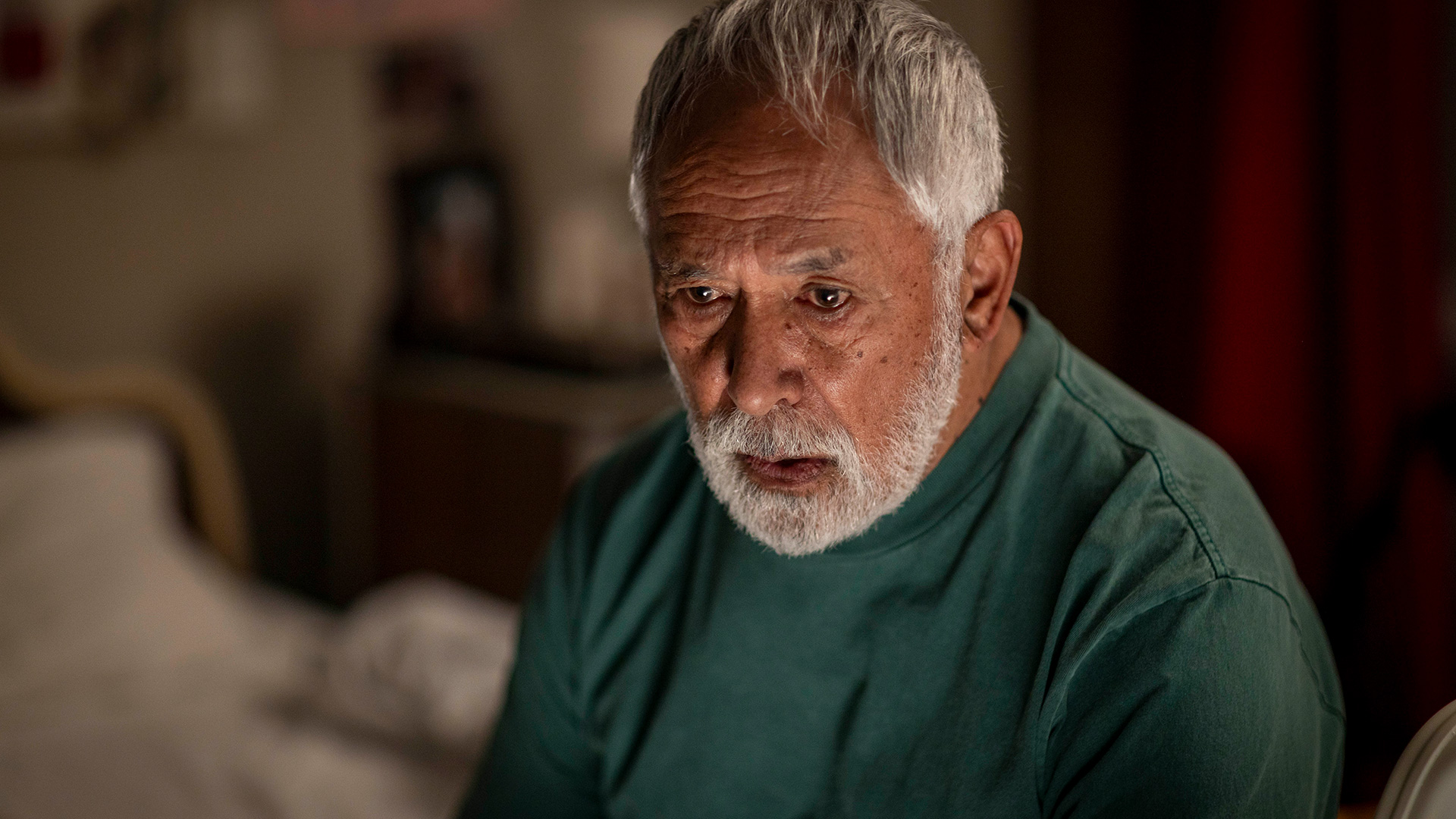

Crealy is a psychopath, and Lithgow demolishes the role, sporting gnarled fake teeth, eerie blue contacts, and an impressive New Zealand accent (often channeled through a hideous eyeless puppet, the Jenny Pen of the title). Watching him command the screen, radiating pure menace, you forget the man is almost 80.

I’d also forgotten how tall he is (1.9 metres), looming over every character he’s placed next to, and often unfurling to full height in the background of shots, Ashcroft cannily keeping him out of focus.

The Paraparaumu-born Ashcroft has appeared in acting roles since the ‘90s, and his 2021 feature Coming Home in the Dark marked him as an important director, an uncompromising slice of local dread that offset its nihilism with deep thought about cycles of violence. Ashcroft brings that same fearlessness to The Rule of Jenny Pen, which gets much weirder and nastier than you may expect (including – TW – sexual assault).

It’s also gross, with piss, spit, and toenails all entering the equation. As well as bodily detritus, there’s a focus on the two leads’ bodies, Ashcroft underlining the frailty of both protagonist and villain (and showing a real lack of vanity from his veteran actors). In fact, the rest home setting might be the toughest element for some viewers: assault and distress are that much worse when it’s the elderly suffering. Mortensen’s struggle to retain his faculties almost feels like a ticking clock, while Crealy waits for his opportunity to pounce.

As the film proceeds, Ashcroft calibrates it into an all-out nightmare, bathing his sets in Giallo reds and greens, and disorienting through camerawork and editing. It’s oppressive stuff, and viewers are rewarded with an ending that’s surprisingly tender given all that’s come before.

Familiar actors are dotted throughout: Paolo Rotondo and Thomas Sainsbury have speaking roles, beloved locals Ginette McDonald and Nathaniel Lees appear in wordless cameos, and Sir Ian Mune devours his brief screen time as the focus of the movie’s best (very, very dark) joke.

All this perhaps speaks to Ashcroft’s esteem in acting circles, and he gives a plum role to another local favourite. I’d argue that George Henare’s Tony Garfield emerges as the film’s most sympathetic figure, if not its actual protagonist.

A former All Black who has relegated himself to suffering Crealy’s whims, Henare invests him with great mana as well as tragedy, and by the end it’s him we really want to succeed. His alternately tender and stoic performance is another good reason to see this complex, frightening film.