Where to watch 5 of Jean-Luc Godard’s finest films in New Zealand

He birthed the French new wave with his breathless sense of cool, but the legendary director’s works are hard to find online.

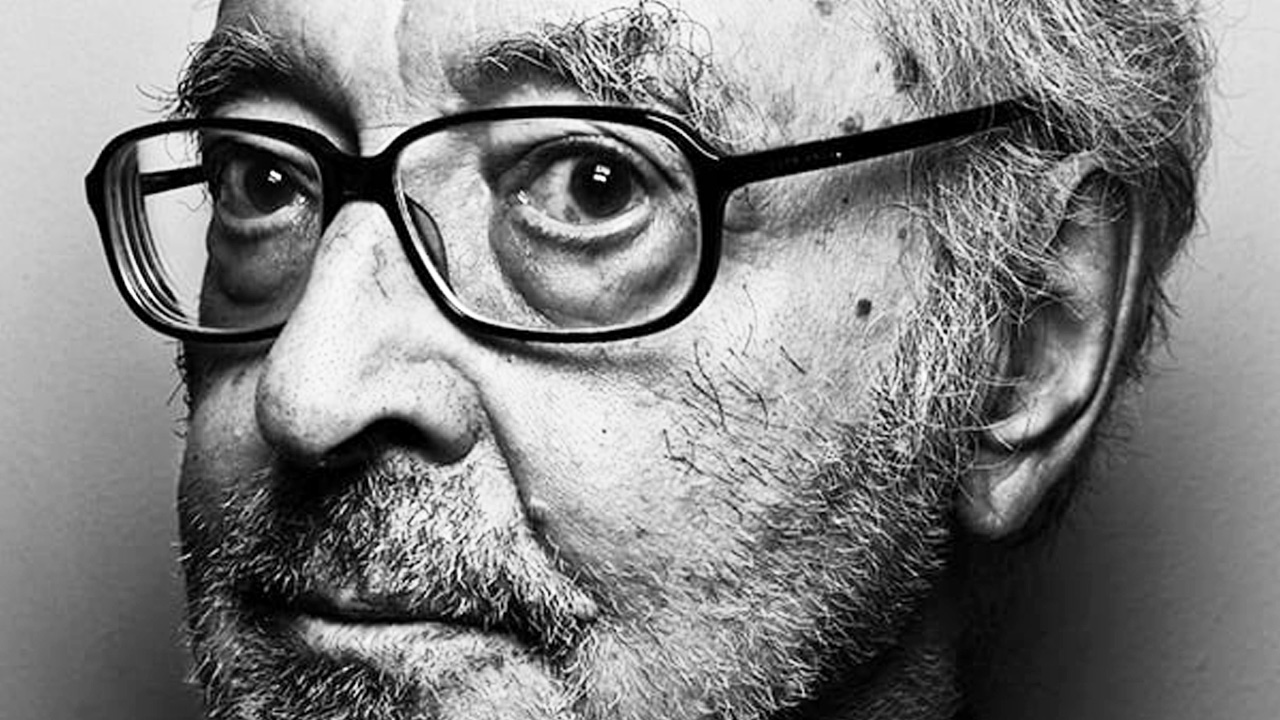

It’s not difficult to see that French New Wave pioneer and influential Cahiers du Cinéma critic Jean-Luc Godard will be sorely missed: by legions of mindblown film school students, critics who’ve lauded him since the mid-century, and his very few remaining colleagues in the genre that shook up filmmaking forever.

Outliving many of his peers to the ripe old age of 91, Godard died on September 13 of assisted suicide in Switzerland. It can be despairingly difficult, however, to find much of his work on streaming platforms. You can however stream five of his best-known films, listed below.

Breathless (1960)

In the 1950s, Hollywood cinema began to flounder: all the biggest ideas in new film were coming from Asia and Europe, and Godard’s brigade of angry young critics in the Cahiers du Cinéma led the European charge. Inspired by older films from Hitchcock and Nicholas Ray, Godard’s directorial debut uses startling jump cuts and noir tropes in a protest against constrictive formal traditions. The film still feels raw today, as we watch Jean-Paul Belmondo (doing Bogart) and Jean Seberg in a criminal jaunt that’s cerebral, stylish, and, well, breathlessly exciting.

A Woman is a Woman (1960)

Belmondo returned for Godard’s second feature, actually filmed after Le petit soldat which was withheld from French release due to its torture sequences. It’s also his first colour film and first released feature with his wife and new wave muse Anna Karina, who plays a dancer caught in a laissez-faire love triangle. She’ll do whatever it takes to have a child, despite her exotic nightlife escapades. One clever sequence has her furiously using book titles to call her stubborn boyfriend (Jean-Claude Brialy) out.

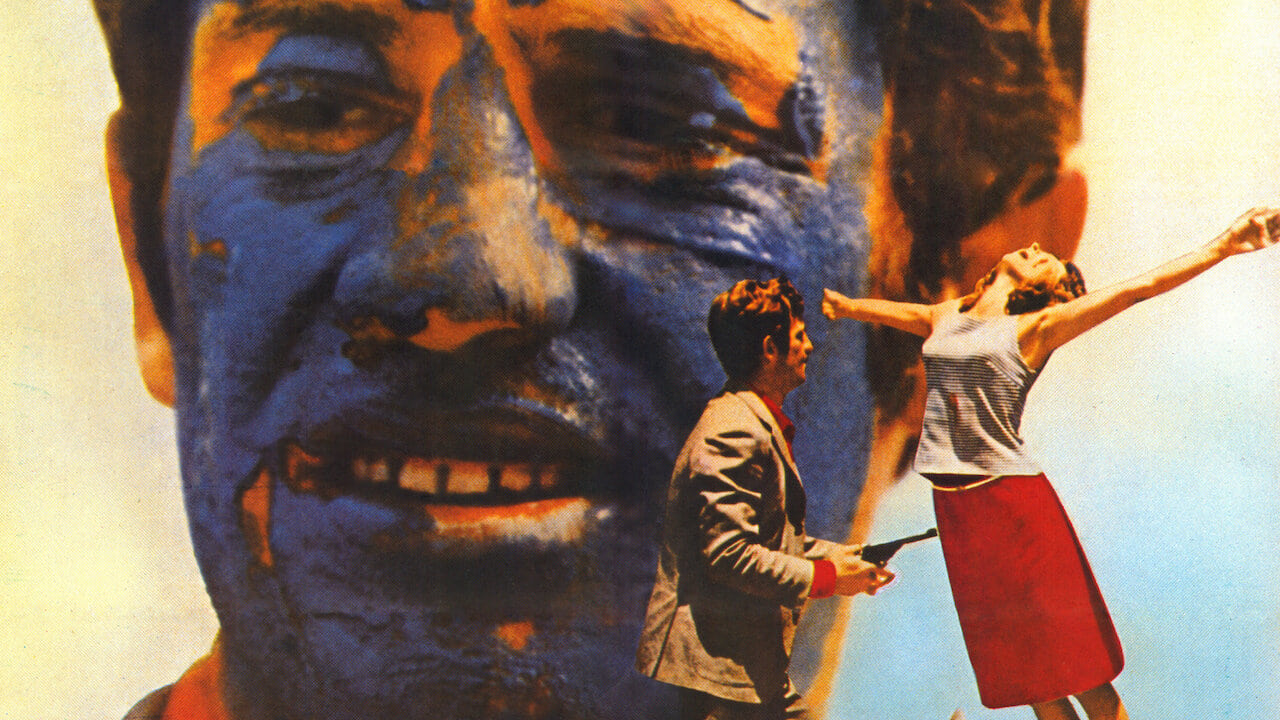

Pierrot le Fou (1965)

By 1965, Godard had already made ten feature films and kickstarted a new school of thought in filmmaking. He was growing tired of himself as an auteur, under the pressures of the very theory he and his fellow renegades cooked up, and that dissatisfaction resulted in perhaps his masterpiece. It’s a self-destructive pop art rebel yell, following Belmondo and Karina again as they ditch a bourgeoisie city life to sink cars (Godard’s own Ford Galaxie), paint their faces blue, and snatch suitcases full of money.

Alphaville (1965)

A lifelong Marxist, Godard got ambitious with this dystopian critique of the capitalist society he saw as alienating and devoid of love—he originally hoped to title it “Tarzan versus IBM.” His typical machismo noir hero (Eddie Constantine) must hold onto his humanity in a futuristic city ruled by the puritanical computer Alpha 60, and his love for its spiritually neutered programmer (Karina) will introduce poetry and unpredictability into a rigid system. Shot in the strange modernist glass and concrete of Paris by night, it’s a more impassioned dystopian tale than many more expensive CGI productions we get today.

The Image Book (2018)

Godard’s final film proved that the master could still bewilder and frustrate audiences into the 21st century, nevertheless earning him Cannes’ first ever Spéciale Palme d’Or. It’s a confronting and chaotic assembly of footage, distorted and saturated beyond the point of recognition—and perhaps of comprehension, mostly making the point that cinema itself can have a destructive impact upon completely unrelated populations around the world. Jean-Luc Godard determined that his filmography would go out with a bang, making something so aesthetically different to Breathless but with the same rabble-rousing ideals.