Why I can’t wait for Final Destination: Bloodlines

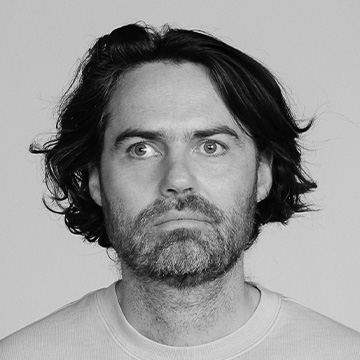

With the first Final Destination movie in almost 15 years arriving next month, Luke Buckmaster explains why he’s pumped—saluting the franchise’s grotesquely innovative appeal.

When I think about the Final Destination movies, I think of the phrase “easy come, easy go.” Each film follows people who evade their deaths through no skill of their own (easy come!) only to be killed off in freakish ways soon after (easy go!. These death scenes are the centerpiece feature, the pièce de résistance, the blood-splotched rug that ties the room together.

From one perspective, these elaborately staged moments of annihilation reflect a view of a chaotically dangerous world, where virtually anything can kill virtually anyone at any time. From another, they suggest the opposite: a world of order and management, in that they couldn’t be more carefully orchestrated, old mate Death taking a MacGyver-like approach to his work and carefully using resources around him to even the ledgers.

Early in the first film, a couple of characters board a plane and walk past a crying baby. One says: “that’s a good sign. Younger the better. It’d be a fucked up god to take down this plane.” That god was listening, and didn’t mind the smear. The place indeed goes down, in a spectacularly visceral way.

Every installment frontloads a premonition scene, whereby one character experiences a vivid vision of their—and other people’s—imminent demise. They make a song and dance about it, freak out, and avoid/delay their deaths. This allows the films to do something rare for horror movies: kill the characters twice. Each opens with a different disaster: a plane crash in the first movie; a highway accident in the second; a rollercoaster ride from (and to) hell in the fourth; another car crash, but at a raceway, in the fifth.

And the sixth? The trailer suggests a family barbeque goes terribly awry. This next installment—Final Destination: Bloodlines—is arriving in May, and I’m pumped. It’s been a long time between drinks—almost 15 years—and I’ve been itching for another sequel for yonks. I’m a big fan of this franchise and its guessing games. Is the tanning bed going to kill someone? The pool drain? Perhaps a falling Buddha statue? The answer to all those question is “yes” (in the third, fourth and fifth movies respectively).

To recap how this works, let’s revisit a scene from Final Destination 2 involving spaghetti and a ladder—not exactly conventional weapons for villains. The death-cheater about to get slayed is Evan (David Paetkau), who comes home and fries up some snacks, zapping old noodles in the microwave. Things start to go south when he gets his hand stuck in his sink. Then, the microwave malfunctions. Then, the fry pan goes up in flames.

By this point we’re aware of the game being played: these elements might directly or indirectly lead to his oblivion, or they might be fakeouts. The big question how each death will unfold, positioning the films in a strange, whodunit-adjacent space (a howdunit?). In Evan’s case, the fire spreads, engulfing his apartment. He escapes out the window and makes it to the ground—only to slip on spaghetti, and get impaled by an escape ladder that falls onto his face. Easy come, easy go.

Later in that film, another character’s death involves a bunch of pigeons. Rewatching it recently, my mind went to The Birds. Perhaps The Final Destination movies finally explain why all our feathered (former) friends went feral: Death was simply fixing his ledgers and feeling lazy. Why configure an elaborate death routine, when you can put your feet up and make a bunch of flying animals attack?

Menace is more palpable in Hitchcock’s classic, the air twisted and choked. But the Final Destination movies are more inventive; their very premise forces the filmmakers into an innovative space, death scenes choreographed like dance routines.

Near the start of the fourth movie, a woman walks onto a rickety old grandstand and asks “is it safe to sit here?” The answer is no…never. Not here, not there, not anywhere.

Throughout the series, the plotting is a bit naff, the pacing can be off, and the performances are generally not great. But these films enter an amazingly surreal space, where inanimate objects—hair pins, bowling balls, books, whatever—become as threatening as Freddy Krueger fingers or Leatherface’s chainsaw. What a great villain: everywhere and nowhere, and very bloody creative.