Writer/director Dorthe Scheffmann on her drama Vermilion

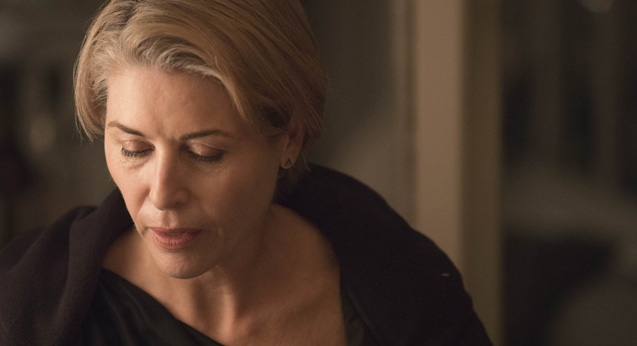

New Zealand acting royal Jennifer Ward-Lealand stars in Vermilion, a drama about the relationships between a group of women—mothers, daughters, friends, and neighbours—that was itself made largely by women, with an 85% female crew. Writer/director Dorthe Scheffmann invited Amanda Jane Robinson to her apartment to talk about a film two decades in the making.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

To you, what is Vermilion about?

It’s a group of people who are as much a family to each other as is possible without being a real family. It’s talking about what constitutes whanau and love. It comes in a lot of different shapes and forms, a chosen family. And of course, then the real issue at the heart of this is the right to choose. And choice, I think, is probably the real theme of this film. Darcy (Jennifer Ward-Lealand) has made choices and some of them she regrets and some she doesn’t. And then there’s the impact of the choices; the nature of her relationship with her daughter, which is a deep love for each other, but it’s not a love based on time spent with each other.

Zoe (Darcy’s daughter, played by Emily Campbell) is clearly more comfortable with the other two women characters. It’s also about the way women support each other. Friendship between women is one of those incredibly strong human relationships. And there are so few films that actually focus on the power of those relationships. Many women would struggle to bring up children without that community of women to support them.

Let’s talk about the cast. This was Jennifer Ward-Lealand’s first feature film in a long time.

I mean, I’m just deeply irritated on behalf of my filmmaking colleagues who are actresses in this community. I first met Jennifer in the late 70s and just thought she was a great actress. Here we are forty years later and the film industry hasn’t made use of this enormous talent. And that’s the plight of women filmmakers, is because at the heart of the women’s film is stories and characters that can be acted, you know? That’s what we need. And again with Theresa Healey, I don’t think we’ve seen her in a major role since Jubilee.

Then there’s Goeretti Chadwick, who plays Sila. I mean, you’d be lucky to work with such a great actress. And Emily Campbell, who plays Zoe. We looked for a lot of Zoes and Emily just had something, a humanistic quality. She’s an incredibly talented musician and smart as a pin. And then Guy Montgomery, my producer Paul had seen his comedy and recommended him. And I’m a huge fan of standup comics and how smart they need to be, I think of Jim Carrey and Robin Williams. So I had a drink with Guy and liked him, I thought he was smart, and so nice. He’s a good person.

Ward-Lealand plays a composer with synesthesia, seeing music as colours. Why the colour vermilion?

That’s the colour she sees and knows something is wrong. She describes it as the “reddest red”. The reason I used the word vermilion and not red is it’s a bit more poetic. I remember being at a classic Kiwi barbeque and a great friend of mine, a painter, telling me with such enthusiasm that he managed to buy this tube of paint in vermilion. I loved the word and I loved his excitement.

What were some of the cinematic references for Vermilion?

I love Bergman. Persona. And Blue, Kieslowski. Requiem for a Dream, I mean. I was trying very hard to make a film made up of distinct images.

Music was also a major element of this film. How early do you consider the soundtrack and score?

I pretty much have the soundtrack as I write. Hunters and Collectors ‘Throw Your Arms Around Me’, it’s the classic antipodean song. And people my age will recognise it, and I am making this film for people my age. I worked with Don McGlashan, who is a very old friend, and it was such a privilege for us to be able to bring three Douglas Lilburn tracks to the audience.

What film experiences influenced you while writing it?

My audience from the first short film I ever made, The Beach, has always been women. It’s not to say I’m not interested in having a male audience, or that I prefer women over men, or anything like that. Growing up in the Waikato those Sunday afternoons come 2 o’clock there was always a movie on. I remember watching Katharine Hepburn, you know, these movies driven by strong women. Then I was really lucky to have a father who loved cinema. He took me to lots of things, and always quite challenging. Zeffirelli’s Romeo and Juliet is one I can remember.

And then there was a film I saw when I was about 14 or 15, I probably shouldn’t have, but it was called Last Summer, and it was such an inspiring film, a real awakener. The next one was Girlfriends, probably at the International Film Festival. I owe the festival a lot, actually. Here was this film that was about two young women living in New York, and it simulated my own life, not that I was quite in New York, but they were dealing with the same issues.

And then, of course, Jane Campion’s Sweetie. I’ve always been grateful to women filmmakers like Isabelle Coixet, Andrea Arnold, Lynne Ramsay, Susanne Bier, Mira Nair. I’m drawn to the cinema of women and that’s why I’m so positioned towards a women’s market. Now I’m a cinema junkie, I’ll go and see everything. Throw an AC/DC track on it and I’m there. But it doesn’t speak to me the way women’s cinema does.