Gaslighting torment of The Invisible Man is perfectly-timed horror

Leigh Whannell, maker of 2018’s Upgrade and writer of Saw films one through three, writes and directs this new take on The Invisible Man (from the H.G. Wells novel and 1933 Universal Studios horror classic), starring Elisabeth Moss.

Turning its focus away from the title character and towards Moss makes for a perfectly-timed horror examining psychological and domestic abuse, the long shadow it casts, and a particularly recognisable vile strain of masculinity, writes Steve Newall.

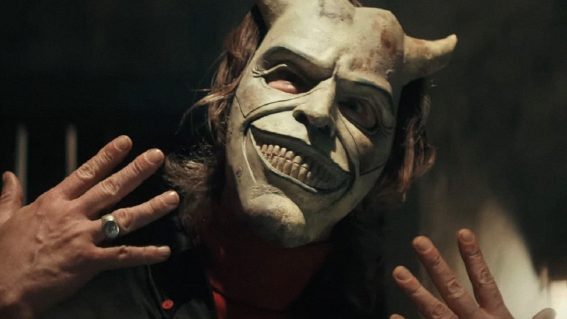

Turning its focus away from the title character as protagonist in The Invisible Man works wonderfully horrifically for Leigh Whannell’s follow-up to excellent techno-horror Upgrade. Elisabeth Moss takes centre stage as Cecelia, who in the film’s opening moments is seen fearfully executing her plan to leave a partner who clearly terrifies her. Rather than treating invisibility as a super-power that we see its wielder have fun with, and go on to be corrupted by, Adrian (Oliver Jackson-Cohen) starts the film as a violent, controlling, egocentric, misogynist piece of shit—which is where he remains throughout, whether visible or invisible, and perhaps even dead or alive.

Instead of Adrian’s journey, Whannell’s choice to focus on Cecilia, anchored by Moss’s winning performance, makes The Invisible Man a perfectly-timed horror examining the impact of psychological and domestic abuse, the long shadow it casts, and a particularly recognisable vile strain of masculinity. Cecilia is haunted by her relationship with Adrian, a man who, as she explains, was obsessed with controlling what she wore, ate, and even thought. While she tries to move on from her ordeal, and soon comes to learn of his death by his own hand, Cecilia finds herself suspecting Adrian’s presence is all too near, invisibly tormenting her—in a scheme to make her doubt her own sanity and isolate her from her family.

It’s invisible gaslighting, which in one scene sees her unattended stove goes up in flames thanks to an unseeable helping hand, perhaps as literal an embodiment of the term that’s possible in an era where we don’t have gas lights to dim in our homes (the origin of the expression, seen in the play Gas Light and 1940 and 1944 film adaptations both called Gaslight, in which a husband makes his wife, and those around her, think she’s going insane by making a succession of small changes to her environment).

Grounded more in the psychological than CGI spectacle, Whannell stills finds opportunities to exploit the screen potential of fearing and fighting an unseen assailant in some gripping sequences. He’s also adept at framing scenes to instill fear that someone’s there—perhaps never has the empty corner of a room or a hallway taken on more menacing overtones.

A fitting 2020 take on its concept and themes without overegging them, The Invisible Man is occasionally confrontingly violent, but also finds the odd humorous moment. During a tense dinner meeting, Cecelia and her dining partner are asked “Have you eaten here before? We do things a bit differently here. Everything’s family style”. Even as the realistic everyday terror underpinning The Invisible Man remains no laughing matter, at least we can appreciate Whannell has experienced the horror suffered by many a modern gourmand.